(this post is a shortened version of the originally published NDSR blog post. This is the first in a series of updates by NYU Libraries Fellow Julia Kim)

While the Digital Library and Technical Services department has long worked to digitize invaluable materials, my post will introduce my National Digital Stewardship Residency‘s task to create access-driven workflows for the handling of complex, born-digital media. My work, then, does not stop at ingest but must account for researcher access. Collections can range in size from 30 MB on 2 floppy disks to multiple terabytes from an institution’s RAID. Collection content may comprise simple .txt and ubiquitous .doc files or, as is the case of material collected from computer hard drives, may hold hundreds of unique and proprietary file types. Further complicating the task of workflow creation, collections of born-digital media often present thorny privacy and intellectual property issues, especially with regard to identity-specific (ex: social security) information which is generally considered off-limits in areas of public access.

At this point in the fellowship, I have conducted preliminary surveys of several small collections with relatively simple image, text, moving image, and sound file formats. Through focusing on accessibility with these smaller collections first, I’ll develop a workflow that encompasses disparate collection characteristics. These initial efforts will help me to formulate a workflow as I approach two large, incredibly complex collections: the Jeremy Blake Papers and the Exit Art Collection. I’ll spend the rest of this post discussing the Blake Papers.

Jeremy Blake (1971-2007) was an American digital artist best known for his “time-based paintings” and his innovations in new media. The Winchester trilogy exemplifies his methodology, which transversed myriad artistic practices: here, he combined 8mm film, vector graphics, and hand-painted imagery to create distinctive color-drenched, even hallucinatory, atmospheric works. Blake cemented his reputation as a gifted artist with his early artistic and commercial successes, such as his consecutive Whitney Biennial entries (2000–2004, inclusive) and his animated sequences in P.T. Anderson’s Punch Drunk Love (2002).

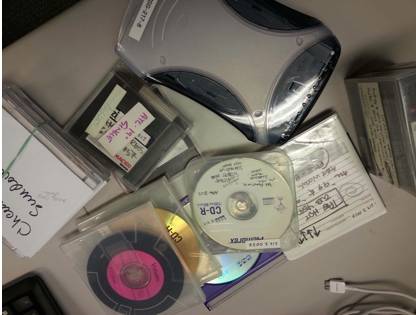

The Jeremy Blake Papers include over 340 pieces of legacy media physical formats that span optical media, short-lived Zip and Jaz disks, digital linear tape cartridges, and multiple duplicative hard drives. Much of what we recovered seemed to be a carefully kept personal working archive of drafts, digitized and digital source images, and various backups in multiple formats, both for himself and for exhibition. While the content was often bundled into stacks by artwork title (as exhibited), knowing that multiple individuals had already combed through the archive before and after acquisition of the material make any certainty as to provenance and dating impossible for now.

Through the work I’ll be doing over the course of this fellowship (stay tuned), researchers will be able to explore Blake’s work process, the software tools he used, and the different digital drafts of his moving images. Processing the Jeremy Blake Papers will necessitate exploration of the problems inherent in the treatment of digital materials. Are emails, with their ease of transmission and seeming immateriality, actually analogous to the paper-based drafts and correspondences in the types of archives we have been processing for years? Or are we newly faced with the transition to a medium that requires seriously rethinking our understandings and retooling of our policy procedures to protect privacy and prevent future vulnerability? While we haven’t explicitly addressed the issue yet, these are some of the bigger questions that our field will need to explore as we balance our obligations to donors as well as future researchers.

At this point, Blake’s collections have been previewed, preliminarily processed, and arranged through Access Data’s FTK software. This is a powerful but expensive software program that can make an archivist’s task-—to dynamically sift through vast quantities of digital materials—even plausible as a 9-month project. While my mentor, Don Mennerich, and I manage the imaging and processing, we’ve also starting discussing what access types might look like. This necessitates discussions with representatives from all three of NYU’s archival bodies (Fales, University Archives, and Tamiment), as well as the head of its new (trans-archive) processing department, the Archival Collections Management Department. In our inaugural meeting last week, we discussed making a very small (30 MB) collection accessible to researchers in the very near future as a test case for providing access to some of our larger collections.

More specifically, we have also set up hardware and software formulations that may help us to understand Blake’s artistic output. In the past two weeks, for example, Don has identified the various Adobe Photoshop versions that Blake used through viewing the files through the hex (hexadecimal of the binary). We have sought out those obsolete versions of Adobe Photoshop, and my office area is now crowded with different computers configured to read materials from software versions common to Blake’s most active years of artistic production. Redundancy isn’t just conducive to preventing data loss, however. We still need multiple methods with which to view and assess Blake’s working files. In addition to using multiple operating systems, write-blockers, imaging techniques, and programs, I spent several days installing emulators on our contemporary computers. After imaging material, we’ll start systematically accessing outdated Photoshop files via these older environments, both emulated and actual.

In the meantime, I still need to make a number of decisions and the workflow is still very much a work in progress! This underpins a larger point: This fellowship necessitates documentation to address gaps like these. That is, while there are concrete deliverables for each phase of the project, in order to deliver I’ll need to understand and investigate intricacies in the overall digital preservation strategy here at NYU. While working with very special collections like the Jeremy Blake Papers is a great opportunity, it’s also great that the questions we address will be useful at our host sites for many other projects down the line.