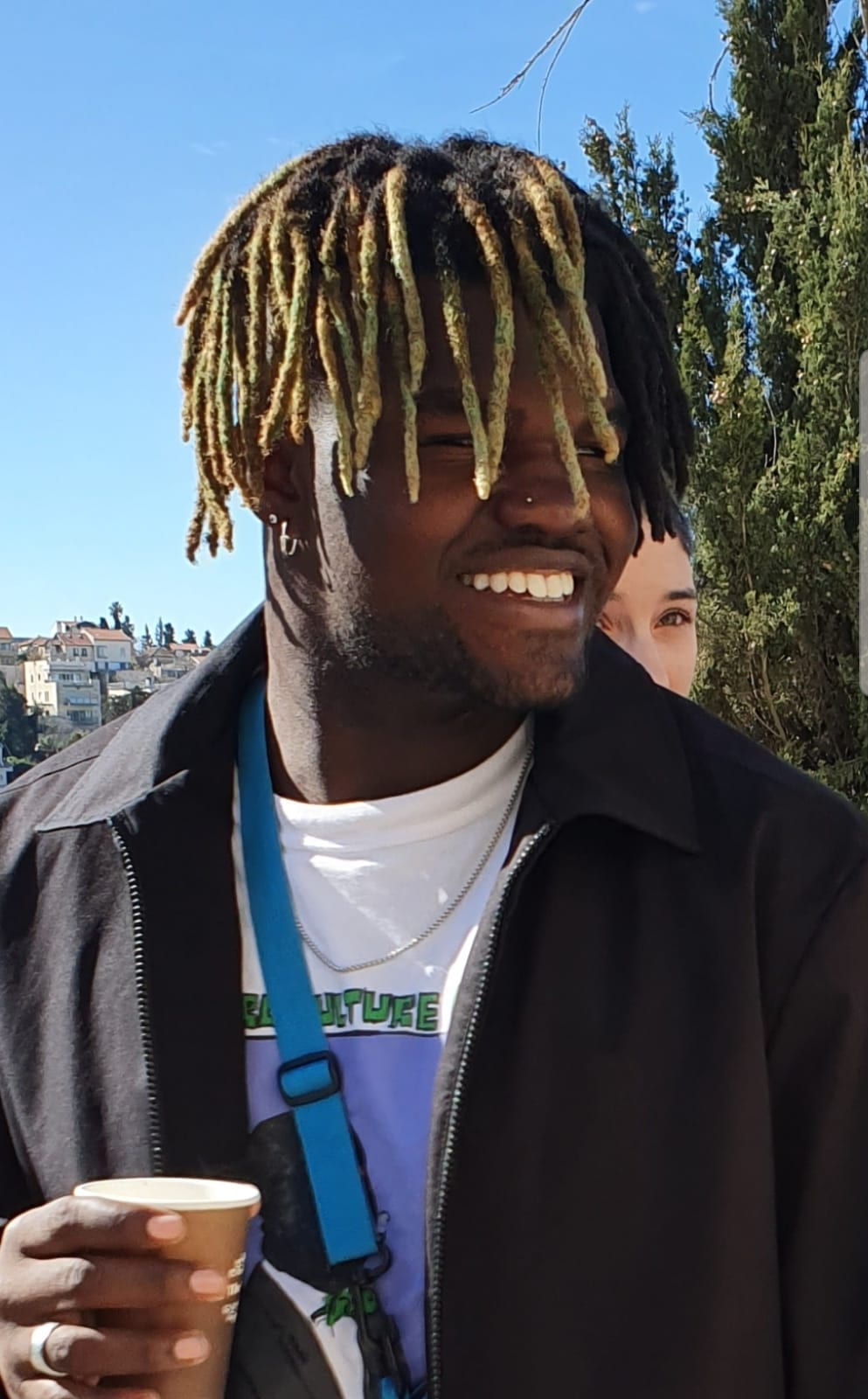

To conclude this series, we hear from an NYU Shanghai student who studied at NYU Tel Aviv, Michael Lukiman.

What is your school affiliation and what year are you? What is your major?

My main campus is NYU Shanghai, though I originally come from Southern California. I am a senior in the first graduating class of this campus, with commencement in May 2017. My official major is neural science, the study and research of the brain.

What inspired you to study in Tel Aviv?

I had heard that Tel Aviv was a business-oriented city, indeed in a place labeled as the world’s “Startup Nation”. Additionally, I felt I had a lot of perspective to learn from such a unique country and region. Similar to the reason I decided to study in South America in the previous semester, I feel that the various segments of the world can have unimaginably different modes of thinking; to fully put the puzzle together, sampling each place by living there can give those different modes of thinking due respect or at least understanding (which can help negotiate conflicts). But ultimately, it sounded like an adventure.

How was your experience? What was most inspiring, surprising, or moving about your time there? What did you find challenging?

My experience was life-changing. I would often walk along the Hayarkon River in Tel Aviv’s North side. What surprised me was just how much it was like California in terms of geography and climate – golden beaches, chaparral, and hiking to boot. There’s a point where you realize that these places were more alike than alien. What moved me was feeling the sun on my skin and looking toward the Mediterranean ocean. What inspired me is the sense of unfaltering unity in the community of Tel Aviv, including that of the NYU staff. It was challenging being a clear foreigner, but even then it was easy to get by with curiosities and the effort to speak the language. It was a pretty safe atmosphere, getting to the statistics of it. More universally, it could be seen as challenging to approach political or cultural elephants in the room, but NYU provided an exceptionally safe space for doing so. Additionally interesting, my technology internship’s locale had me walking by goats, cows, chickens, and pastures – a peculiar and outstanding way to stay connected to nature in the “tech” sphere.

I understand that you interned with Israel Brain Technologies while at NYU Tel Aviv. Can you tell us about how you came to intern there? Is this an academic internship or non-credit internship?

I like the feeling of creating something unique and emotional – and curious about how things work (and how we can make them work), notably the brain. When mixing this startup spirit with my academic major of neuroscience, finding Israel Brain Technologies allowed me to handle practical, real, and serious implementations of neuroscience-oriented ideas on a daily basis. I’d like to thank Ms. Ilana Goldberg, the internship coordinator, for being a very effective and important liaison in finding this perfect fit. I interviewed with her over Skype a couple months prior to starting, and everything was connected for this non-credit internship (it provided much more value than a couple credits). In this startup accelerator supported by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman and former prime minister Shimon Peres, I worked closely with Miri Polachek and Yael Fuchs to get involved in all levels of an industry where business, science, and entrepreneurship lock eyes.

What did your work involve? How did you find the experience?

In an accelerator, there are multiple stages: first, you need to select which companies are promising and worthy of your resources, then spend months polishing their efficiency, marketing, and product through training and meetings (because nothing is perfect off the bat), and finally, connect and demonstrate their value to the investors. I had privilege of helping to organize the judging rounds to decide which final dozen or so of the upwards of fifty companies would come under IBT’s wing, thereby earning me the key opportunity to sit in on the board meetings and serious decision-making discussions behind the table. How does an idea go from paper to effectively profiting and providing value in the community? I played a part in learning the financing infrastructure of such an institution, as well as being able to connect one-on-one with entrepreneurs of these companies, in Israel of all places, the country with the most startups per capita. More importantly, I could learn what life was like day-to-day in an industry like this – the meetings, the organization, the challenges, the jargon, hierarchy, and not to mention how long their workdays were.

As I understand it, Israel Brain Technologies is a non-profit that seeks to accelerate the commercialization of Israel’s brain-related innovation and establish Israel as a leading international brain technology hub. Did being there feel as though you were at the crossroads of the non-profit, tech and start-up worlds? How would you best describe the organization, its mission, and how it influences the development of brain technologies?

Yeah, it was definitely a sweet mix of all things entrepreneurial and scientific! Moreover, it was grounded. There were no obsessive metrics, although there was an emphasis on overall social impact and how much money would be needed. You could emphasize simple rules like: Who would use this? Why is this important? Why is it better? How do we get there? What’s the market like? Is it possible? Is it efficient? When you mix the detailed pace of truth-finding science with the expedience of business, it kinda becomes like engineering. The mission of Israel Brain Technologies to me was to address a silo of business that we once saw as impossible or overly complicated – empowering companies with exciting ideas, some of which sought to allow you to control machines just with your thoughts (not physically impossible), or companies that were out to cure and assist those with Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and other disabilities. These are companies that, if successful, could add thousands of years of quality of life around the world – and some of these breakthroughs are already in practice today. That’s invaluable. To make these groups successful, we need to think about money, resources, and how to get themselves to the people that want to hear about them. I knew this internship was genuine because the type of the people working there – many of whom are mothers who are wonderfully leading the mission while managing to care for their kids. Those concurrent activities vest you into anything you do.

Do you feel as though the work you did as an intern has been valuable? Has working for Israel Brain Technologies changed your understanding of innovation is promoted? Or the various manners in which we are seeking to use technology for the brain? If so, can you describe how?

In every internship, my main objective is to learn insights and work my way up a knowledge, wisdom, and community ladder. I like the simple heuristic to provide a new conceptual continent, or at least district on the map, so to speak. There, one could either mentally rest or return to when needed. Israel Brain Technologies has given me the most in terms of this, where I can think about science in relation to business and money, and hence what I’m studying in relation to what other people are experiencing. I learned that starting a company is both overwhelmingly complex and simple. I learned that pressure is just reflective of how much you can offer – if you aren’t thinking in the right mode, no matter how hard you try, you can’t get into the right arena. Most of all, it assured me that neuroscience is still the promising new frontier that I first saw when choosing it for my initial college career – generally, anything that most people can entertain as science-fiction and then be surprised about when someone tells you it’s a real product is society’s current sweet spot of discovery. On the honest flipside, I learned that lots of people don’t have what it takes to really think in a risk-welcoming, conflict-welcoming endeavor while still focusing on the big picture. Something gets in the way and creates tunnel vision with the companies that we didn’t accept, either pride, doubt, or lack of enthusiasm. You’ve really got to objectively focus on what you’re doing, at least if you want to make it exceptional. Either have a good track record or a good spirit – anything less, you can imagine people will not demand as much. That’s just a lose-lose for both you and the people. For startups, this means accepting when something is just a plain bad idea, or maybe realizing that something is a good idea when everyone else says it is bad. For neuroscience, there’s a realization that anything a brain can do, a computer may eventually do, given some bureaucracies. This fact in turn humbles anyone. A brain just just another component which we can funnel technology through; it can decay or be sharpened. So I think it’s logical use it wisely by getting an internship that keeps it on its toes.

How do you feel your internship experience has complemented your academic experience at NYU Tel Aviv?

It’s hard to think of a way which my classes related to my internship. That’s probably a good thing, since sticking to one main behavior in a new country can easily put a cone around your head to experiences. I mostly took politics courses, as well as a linguistics course about Hebrew, Arabic, and other languages of the region. It’s a cop-out, but I can say that language and socially/tribally-driven politics has a reserved space for neuroscience because knowing the brain can help us anticipate and navigate these once irreducible landscapes. It’s what I’ve always said to myself. But one could say that about any field. In my classes, we talked about dictatorship, religion, and all sorts of controversial things. I do have to say that it’s a good exercise to think how our brain is lighting up when discussing these topics that are close to home, where so much identity is on the line for a lot of people. There may be a latent element there that can help us prevent conflict and ease tensions, just like how we discovered more empathy and personal stories can increase donations to charity. Another link is that running successful companies and running successful governments have their parallels, although on different scales. One similarity is that you’ve got to care for your people or else you’re not going to have a good time.

Has your time studying at NYU Tel Aviv or your experience in either internship informed your thinking about your future plans? If so, how?

Because of these experiences in Tel Aviv, I realize there’s a lot of work to be done not only in creating new things but fixing old ones. So it’s Silicon Valley with a more evocative twist. It put me on the other side of the table – after judging other companies, now I judge myself: I have my work ethic, and that provides a certain amount of value to people. How much does brain research mean to a government or economy whose main metric is still profit or gross output? How much will working 100 hours a week and dotting every “i” marginally increase what we can do opposed to what I can experience or share with other people outside of work? And how much are my genetics and environment really going to allow me/us to accomplish? These are questions that being on the other side of the table taught me. There’s a generic match in every institution, and being in Tel Aviv thinking of different governing styles and judging different companies begged the question to find what unique features groups really need to break ceilings. Ultimately, this experience in Tel Aviv showed me the real world of business as well as the real, firsthand world of political strife, as far as I know of course. In other places, we may take big corporations and an established government for granted, whereas they are only as solid as allowed, not to say that they’re not strong. That is, although there’s a lot to learn, life has become a bit more transparent, at least to a 21-year-old me, through this experience.

Is there anything else you’d like to share about your time in Tel Aviv or while at NYU?

I recommend an experience like this, especially if you think you don’t quite fit the bill, because the abrasion may just provide pearls of insight.