This post comes to us from NYU Sydney Instructor Adam Gall, who teaches Australian Environmental History.

This post comes to us from NYU Sydney Instructor Adam Gall, who teaches Australian Environmental History.

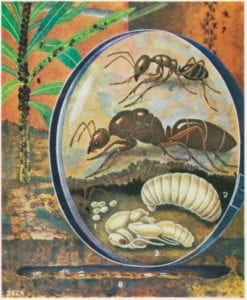

We tend to see ants as objects of benign curiosity or perhaps annoying interlopers in our gardens or kitchens, but when the Argentine ant appeared in Australian cities and suburbs in the mid-twentieth century it was already understood as a significant pest species. These unassuming little brown ants were emerging at the time as a global problem, infesting people’s home in large numbers in Mediterranean Europe and the southern United States, and generating a great deal of attention among scientists and policymakers. They likely arrived in Australia via the global shipping networks that connected this country with the rest of the world, though their exact date of arrival remains uncertain. As they traveled to new places, they went through a population bottleneck. Instead of being surrounded by diverse, rival colonies of the same species (as they had been in their home range in northern Argentina), Argentine ants in Australia were part of one group and able to cooperate against native species and compete with them for food resources. Their arrival prompted an enormous effort to control their numbers and, in Sydney at least, to eradicate the ants entirely using pesticides.

In a new chapter, “On the ant frontier”, written for a forthcoming edited collection, Animals Count, I narrate the history of these creatures in Sydney. The focus of my research has been on records left by the Argentine Ant Eradication Committee, the government organ which oversaw the eradication initiative in New South Wales. These files are held in the State Archives in western Sydney, at a compound situated on the rural fringes of the metropolitan area. They contain all sorts of documents, including weekly reports from field officers, invoices for equipment, letters from members of the public, articles and pamphlets, as well as plans for publicity campaigns. At the forefront of the work were entomologists, the insect scientists who developed techniques for identifying and spraying Argentine ant nests, and their reports and expert contributions have been fascinating to dig into, too.

The fact that the ants were domestic pests put the campaign on a collision course with suburban middle-class people and their growing awareness of the environmental effects of organochlorine pesticides. Already in the 1960s there were household pets affected by chlordane spray, and people complained about this to the Committee and sought compensation. There are even stories of citizens standing in front of the spraying carts or refusing access to their land because they recognised–against the official positions of government and chemical companies–that these were dangerous poisons. This is all part of a global history, too: around the world, more and more citizens and activists tried to prevent the use of organochlorine pesticides, partly because of the influence of Rachel Carson’s powerful writing in The Silent Spring. There pesticides were used because they were seen as more environmentally friendly than other chemicals, and the eradication campaign was undertaken to protect people’s sense of everyday wellbeing and household amenity. Eventually, citizens and their representatives in the northern suburbs of Sydney–particularly in leafy Lane Cove–challenged the right of the ant unit to spray. In 1985 the campaign was formally ended by the state government, though the ants themselves are still seen as a huge threat to biodiversity in many places around the world.

I found this journey through the archives very interesting as a historical researcher, because it had a defamiliarising effect on the spaces of my everyday life. I grew up in this city in the 1980s and 1990s and had never heard about Argentine ants before beginning this work. I found that whenever I mentioned my topic to people I met, they would say things like ‘Oh, I remember the TV ads!’ and talk about the Trapper Tom character, and about collecting samples to send in to their local councils as kids. There is a whole submerged history of ordinary people–particularly those who were children in Sydney during the 1960s and 1970s–being really invested in the campaign against the ants through popular media.

As new campaigns begin against other species, such as fire ants in Queensland, it is fascinating to see patterns repeating. History prompts us to ask difficult questions about the decisions we are making now. While it is happening, we feel with great urgency the threat of insects infesting our homes or suburban spaces. But we should also recognise that there is usually much more going on, from the effects of changes to land use to the potential risks of whatever substances we use to control pest species.