In Argentina, football is sacred. The beautiful game is widely watched — and worshiped — often with deep passion. Unfortunately, descriptions of the passionate Argentine fan can at times veer toward stereotype, and two NYU Buenos Aires students decided to contribute to a local project trying to address the negative stereotypes of football fans, which they viewed as unfair representations.

In Argentina, football is sacred. The beautiful game is widely watched — and worshiped — often with deep passion. Unfortunately, descriptions of the passionate Argentine fan can at times veer toward stereotype, and two NYU Buenos Aires students decided to contribute to a local project trying to address the negative stereotypes of football fans, which they viewed as unfair representations.

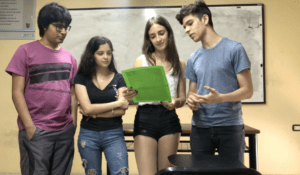

Leila Al Dzheref, a sophomore at NYU Abu Dhabi, and Arik Rosenstein, a junior at the School of Professional Studies, thought sharing stories about “regular” Argentine football fans would go a long way in dispelling the notion that the country’s football fans’ passion somehow by definition violent or barbaric. They developed a project, El Mismo Amor in Passion FC, provides a different perspective by sharing stories about “regular” Argentine football fans. Al Dzeref and Rosenstein recently became involved in the Passion FC movement, hoping to highlight the real mindsets and beliefs of Argentine football supporters because they believe it is important to share these stories. Passion FC existed as a social movement before the students arrived in Buenos Aires, but they were able to make a contribution and remain active.

Passion FC was founded in Buenos Aires 2018 by local football fans hoping to engage others by creating a space for conversations around football. They have a website and social media presence, and sometimes organise events. The NYU Buenos Aires students’ El Miso Amor project was a series of Instagram stories. Passion FC released these stories to raise awareness about the misconceptions of Argentine football supporters.

Passion FC was founded in Buenos Aires 2018 by local football fans hoping to engage others by creating a space for conversations around football. They have a website and social media presence, and sometimes organise events. The NYU Buenos Aires students’ El Miso Amor project was a series of Instagram stories. Passion FC released these stories to raise awareness about the misconceptions of Argentine football supporters.

Although it was Al Dzheref’s interest in learning Spanish that led her to study at NYU Buenos Aires, she is a huge football fan, so saw this also as a great opportunity to explore the culture of Argentine football. Rosenstein’s passion for sport has inspired him to pursue a BS in Sports Management, Media, and Business at SPS’ Robert Tisch Institute for Global Sport. He said he chose to study at NYU Buenos Aires in part because his experience studying at NYU Accra in fall 2016 was so positive that he knew he “needed to have another unique and different experience.” Rosenstein immediately started attending football games and, like Al Dzheref, was keen to experience Argentine football culture.

Together Al Dzheref and Rosenstein started working with Passion FC, focusing on using football to facilitate conversations around contemporary social issues in Argentina. They developed their project, El Mismo Amor or “the same love,” after becoming acquainted with enthusiastic and kind fans of Argentine football. Despite being advised to be wary of certain clubs or neighborhoods because the football supporters were “animals” or “barbarians,” the two went to many matches and engaged the Argentine fans they met in conversation. According to Rosenstein, they “asked Argentinian supporters about their love of football and also about the common negative stereotypes of fans.” They found people eager to talk and after “moments of pure and authentic connection,” they realized that although football may be supported in different ways, the love of the game is the same.

The stories highlighted in El Miso Amori illustrated the vibrancy of Argentine football cultures and fans. One story focuses on Naza, whom Al Dzheref and Rosenstein met at a match in Lanus, a city just south of Buenos Aires. After asking him where they might purchase a Lanus team scarf, Naza invited the students to sit with him and explained what it means to be from Lanus. Bonding through football, they learned so much more about his life than they would have without that common interest.

Another story features Camilla, whom they met at a Velez Sarsfield match, the very first match Al Dzheref and Rosenstein attended in Buenos Aires. She was with her high school friends, and they bonded over being pushed and pulled by the other supporters. According to Rosenstein, “We had in-depth discussions about why Camila comes with her friends, her viewpoints of the team, the experience and of course her love of the game. Being welcomed by a group of highschoolers with no need to talk to us, shows just how many connections and social differences this game has.” The students found that Camilla and her friends valued showing them what it means to be from Velez. They left knowing that the next time they would go back, they would have friends at the stadium.

Al Dzheref and Rosenstein are quick to emphasize that they do not mean to imply that are not serious issues in Argentinian football or that all stadiums are safe. Rather, they say, “El Mismo Amor is about having a conversation.” They explain that it is about considering another culture, respectfully challenging other views or opinions. According to Al Dazheref, seeing the passionate commitment of the Argentinian football fans inspired her to “want to change their representation for the better.” Through El Mismo Amor they are “showing another side of football, not the side of fights and violence that is usually reported in the media.”

Al Dzheref and Rosenstein are quick to emphasize that they do not mean to imply that are not serious issues in Argentinian football or that all stadiums are safe. Rather, they say, “El Mismo Amor is about having a conversation.” They explain that it is about considering another culture, respectfully challenging other views or opinions. According to Al Dazheref, seeing the passionate commitment of the Argentinian football fans inspired her to “want to change their representation for the better.” Through El Mismo Amor they are “showing another side of football, not the side of fights and violence that is usually reported in the media.”

The El Mismo Amor project, via the Passion FC website and social media channels, has reached over 90,000 people, according to Rosenstein. He and Al Dzheref collaborated on sharing seven individual stories on Instagram, painting a picture of the different football cultures. The responses and the ensuing conversations have been positive and resulted in dialogues and debates about the public perceptions of violence in football and football fans, something Rosenstein believes demonstrates effective advocacy online. Al Dzheref finds that the move to remote learning because of COVID-19 has allowed them to think strategically about future campaigns and effectively sharing content.

Both students remain active with Passion FC and Rosenstein emphasizes they only “met because of NYU’s global commitment, so it’s a testament to NYU.” Al Dzheref is enthusiastic about her time at NYU Buenos Aires saying, “My experience in Argentina was one of the best in my life.” She was grateful for the opportunity “to see Argentina through my own eyes, without the distortions of others.” She and Rosenstein are similarly trying to open eyes through this project and encourage us to engage in dialogues about stereotypes and assumptions in Argentine football.