October 2016 marked the 20th anniversary of the Forum 2000 Conference, founded by former Czech President Vaclav Havel to support the values of democracy, respect for human rights, assist the development of civil society, and encourage tolerance.

NYU Prague has long had close ties to Forum 2000, as Jiri Pehe, director of NYU Prague, was chair of the program committee for ten years, and many NYU Prague professors currently act as organizers and delegates in the program. Building upon these connections, NYU Prague students have the opportunity to participate in the conference, gaining access to world-renowned politicians, activists, academics and journalists. Students can also apply to intern for the Forum.

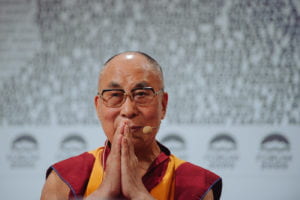

This year, NYU Prague students had the chance to hear His Holiness the Dalai Lama – Nobel Laureate and an exiled Tibetan spiritual leader – speak about compassion in world politics, as well as dozens of other world leaders discuss the conference topic: The courage to take responsibility.

This year, NYU Prague students had the chance to hear His Holiness the Dalai Lama – Nobel Laureate and an exiled Tibetan spiritual leader – speak about compassion in world politics, as well as dozens of other world leaders discuss the conference topic: The courage to take responsibility.

Anand Balaji, a finance/economics major in Stern Business School, interned at this year’s Forum. “It was an incredible event that I never in my wildest dreams thought I would get access to as a sophomore in colleg,” said Balaji. As part of his responsibilities, Balaji reported on a panel about the philosophies of Havel and Gandhi, and also met Philip Zimbardo, psychologist and the leader of the Stanford Prison experiment.

Petr Mucha, professor of religious studies at NYU Prague, and member of the Forum 2000 program committee, invited his students to attend the Dalai Lama’s talk. Reilly Hilbert, a double major in religious studies (CAS) and acting (Tisch), shared her experience.

“We must make earnest of love and compassion in secular education. Not tying it to the next life, to heaven or hell, but to the present, with the understanding that harmonious living can only be achieved under compassion” —His Holiness the Dalai Lama

I am sitting in a white room in a very modern building, across the way from a very old building, on a small island in Prague. I am twenty minutes early and sweating because it’s not quite cold enough for my big coat, but too cold for my smaller one. I’m sitting in the second row, to my left is a political leader of a country of 46,000 discusses with two of his colleagues the reality of Trump’s systematic lies. To my right, a woman from India, hands folded, head down, mouth moving in what I think is a prayer. The Dalai Lama enters, everyone stands, and he shakes hands with people in the first row, and when he gets to my end, he sees the woman to my right and reaches out to her, over the bodies of the first row people. They exchange a few words, and she says, “Thank you for your blessing.” He waves at me, I smile and wave back, feeling both very big and very small at the same time. The woman next to me says, “He knows I’ve been praying for this.”

Praying for this. I am Catholic. I am a Catholic woman negotiating being also an artist, activist, actor, student, daughter, sister, friend and girlfriend in the 21st Century. It is painful, it is difficult, and I frequently find myself searching for truths in Religious Traditions that are not my own. In this way, the Dalai Lama let me down. His mission is Love, his mission is Compassion, Unity, and Togetherness. And where have I heard this before? In every homily, on every retreat, and in every meditative prayer I have had the opportunity to hear, see, and do. On every Krista Tippet On Being podcast, in every one of the numerous books that I’ve read about the potent experience of Religion—be it Catholicism, Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, or Buddhism, I have heard the same word: Love. And as I sat five feet from one of the Holiest men alive right now, I was disappointed to hear it again. Instead of feeling fulfilled and alive because of this ever present notion of love that surrounds me in everything I have been given the opportunity to do, I was sad that there wasn’t some magical new way of connecting to the world. As I continued listening to the other speakers, I worked to identify where this seemingly unfounded pain came from.

Tarek Osman, author of the popular book Egypt on the Brink, and another panelist in the conversation with His Holiness, helped me investigate this dissatisfaction. Osman said that “Religion can put forward order, but there is a very thin line between order and control.”

Tarek Osman, author of the popular book Egypt on the Brink, and another panelist in the conversation with His Holiness, helped me investigate this dissatisfaction. Osman said that “Religion can put forward order, but there is a very thin line between order and control.”

I remembered, while he was speaking, the model brought forth by Stephen Bush of religion as being essentially based in three things: power, meaning, and experience. The Dalai Lama’s notion of boundless love, compassion for all people, is all well and good, but Osman also grapples with negative aspects of the power religion has.

Catholicism for me has been very powerful, in both positive and negative ways, and it can be difficult to sort out. So the fact that love can seemingly be used however it best works for people does not fit in the binary that instilled love in me in the first place. If religion can be used as a tool to harm in the name of love, it can be placed in a binary “evil” category. But if religion is only a source of “light and love,” it might be “good” but it disregards the evils present in societies today that are carried out in the name of religion. This is where the unrest began to clarify itself.

The third panelist, Daniel Herman, the Czech Republic’s Minister of Culture, spoke about the crisis of modernization, explaining that post-Communism, he finally understood the Jewish Exodus. It took 40 years to renew, it took several generations to reestablish, and it was not only a physical renewal, but a moral one. He explained that the Czech Republic is only in year 26 of its own “Exodus,” and said that many societies today are in the middle of their desert.

In the United States, he added, Americans are still in their own desert, coming out of slavery, World War 2, Vietnam, and the women’s rights, civil rights, and gay rights movements.

And maybe that is why love is so difficult for me, because in my binary brain, love should be easy, natural, and something we can just do. But I know better than this. I know love is actually the most difficult thing in the world. It goes against the tendency to compete, to overcome, and to win. It goes against the tendency to control, to possess, and to know. Loving is not knowing. Loving is learning, it is hoping, it is working, and it is hard.

The Dalai Lama also said we need to be more active in love. We need to strive for teaching love in secular education, because love, though incredibly difficult, is a universal idea. And love is what will bring us out of our deserts. Not romantic love, not familial love, but a love for humanity that is so often forgotten in our world of immediate gratification and confusion.

The Dalai Lama said, “When I lived in isolation in Tibet, Buddhism seemed the only way, then I went to India.” There is not one right way to negotiate love. There is not one path. And this recognition of unity beyond objectivity is what can open us to love in all its difficulty. I’m praying for this.

I want to say thank you to Professor Mucha for giving me the opportunity to attend this conference, as Religious Studies is not only my major, but also very close to my heart, and so I feel grateful not only for the learning experience, but for the personal growth it helped me obtain.

Photos taken from the Forum 2000 website here.