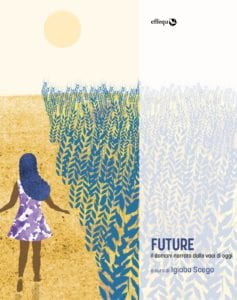

Angelica Pesarini is a Lecturer in social and cultural analysis at NYU Florence. She contributed an essay to a recently published literary anthology, Future. Il domani narrato dalle voci di oggi, which focuses on the diversity of Black Italian women’s experiences. The book shares moving and important stories about the experiences of Black women in Italy amid systemic injustice. This is Italy’s first published literary anthology by Black Italian women and it explores how the political is personal and vice versa. We caught up with Professor Pesarini to ask about her contribution to this ground-breaking and illuminating work.

1. What inspired you to contribute in this anthology? What themes do you hope that the book illuminates for readers?

I was contacted by the curator of the volume, the Italian Somali writer Igiaba Scego, and she asked me if I was interested in taking part in this project – a collection of stories on the idea of future written by a number of Afro-descendent, Afro-Italian women. This was a challenge for me because in my work as an academic I write a lot, but in a very different style. I write dry, probably boring, academic essays, book chapters, articles. But writing fiction, a narrative, was something that I always loved to do but had never done. I decided to accept also for the political and cultural weight that this book could have because it was the first time that a similar book has ever been published – a collection of stories written by women who are Italian and black and brown. The theme that the book seeks to illuminate is probably this condition – the complicated realities of being a black or brown Italian citizen, or of being Italian by culture, by birth, but not on papers. The book asks readers to consider what it means to be Italian, how do we measure Italianness, and how race is connected to the dynamics of national identity.

2. How do you think the book might shift current understandings of the historical and contemporary anxieties about race experienced by Black Italians?

2. How do you think the book might shift current understandings of the historical and contemporary anxieties about race experienced by Black Italians?

Many readers have told me that the book was definitely an eye-opening experience for them. We are doing presentations all over Italy and hear these kinds of comments quite often. We receive many requests form libraries, theatres, book shops, and elsewhere and we have discovered that there is a great deal of interest in hearing from us. The book is doing really well and we are now on the second or third reprint. So, this really tells us that people in Italy are interested in exploring and understanding the experience of Black Italians. They want to know more. And by reading this book one really understands how race is connected to national identity through the idea of blood. This is also quite central in my own story in the anthology.

3. In your own short story, the main character, Maddalena is orphaned and is seen as an illegitimate child of the state whose narrative is never her own. This seems a tragic fate for a child. Can you comment on the creation of this character and what her story reveals about the Italian state and its relations with Black Italians?

My story is based on a real story. I changed a few things, but the context of the story and the documents used in the story are real. The main character, Maddalena, is a child born in 1913 by an Italian father and an African mother. What we know about Maddalena we learn it through the official documents written by the institute where she was left and raised in Asmara, Eritrea. These kinds of institutions were called in Italian collegi and were orphanages managed by Catholic missionaries with the support of the early colonial governments and later on the Fascist regime. At the time the story begins, Maddalena is eighteen and she doesn’t want to fulfil what is expected from her as a young mixed-race Italian woman. The expectation is that she will become a good maid in an Italian family. The girls and the boys raised in these institutions, which were gender- based, were trained to become maids or manual labourers, respectively. The girls were taught how to clean, how to cook, how to look after a house, because this was what was expected from them. Maddalena refuses to become a maid and instead she wants to work in a governmental bureau. We come to understand and know her through letters and documents. We learn that her father was an Italian man who initially acknowledged her and her brother. He paid the monthly fees given to the institution to look after them. But then, at some point, he disappears. The institution continues caring for the two children despite the lack of support from the parental figure, a very common situation in these cases. I read many archival sources and in most of the cases the father was absent. We don’t know anything about Maddalena’s mother, though, which is also interesting. Her mother seems non-existent. This was really striking for me. Not even a single word is said about her, it is just about the father and the absence of this father.

This story also tells us a lot about Italian colonialism. In Italian historiography especially, it is very difficult to talk about the colonial past due to a sort of collective amnesia and a romanticized vision of the colonial experience. So, unlike the British or the French, Italians believe that they were not as bad. There is a very recurrent myth which says Italiani brava gente, “Italians are good-hearted people.” The narrative is that we went to Africa, we built streets, we built hospitals, and barely got anything from it. This is a very revisionist telling of history because Italy’s presence in East Africa lasted over than sixty years. Italian colonialism, like every form of colonial oppression, was very invasive and violent. In this process people and communities were displaced, tortured and killed. At the end of World War II, the former Yugoslavia, Greece, and Ethiopia made a list of twelve hundred Italian war criminals that they wanted to bring to court and this never happened. In Italy we never had the Nuremberg process and so this never gave us a sense of public punishment for the war criminals and public reckoning of the association of Italy with Nazi Germany until 1943. This is a very difficult page of history for Italians to admit and so there is this idea that the colonial experience was short, not important and we moved on. But, of course, this is not true because the legacy of that period remains still visible today.

Just imagine that I take the students who attend my course at NYU Florence called “Black Italia” to Rome every semester to see the heritage of the fascist monuments and they are always shocked to see, for example, the Mussolini Obelisk. This is a huge obelisk in the North of Rome, in front of the Stadio Olimpico, on which it is written “Mussolini Dux.” This would be like to going to Berlin, to the Brandenburg Gate, and seeing an obelisk that says “Heil Hitler” standing there. It’s impossible to think, right? Well, in Italy we have such a thing. And we have so many fascist monuments still standing, completely decontextualized that one may wonder how is that possible? A couple of years ago professor Ruth Ben-Ghiat, who is one of the major experts on Italian fascism and teaches at NYU-NY, wrote an article in the New Yorker entitled, “Why are so many fascist monuments still standing in Italy?” in which she did a brilliant analysis of the lack of context and the denial there is in Italy on the fascist past. The reception of the article was awful, and she received so much hatred, misogynist and anti-Semitic comments. So, it was really a striking moment.

5. Has teaching at NYU Florence informed your writing at all? If so, how?

I think it has, definitely. When I was hired to teach Black Italia, I was given complete freedom. NYU, and in particular Jennifer Morgan, the Chair of the Department of Social & Cultural Analysis, trusted me in building a new, solid and rigorous academic course. And so, I had to really think on how to put together fourteen weeks of academic content that would give students coming from New York, Shanghai or Abu Dhabi an idea of Italy’s history of racial identity. And by doing that, I had to think about the major historical and cultural steps that brought about Italians’ national identity and racial formation. Fascism, clearly, was an incredibly important moment. Though, even before Fascism, in the very beginning of the Italian colonisation of Eritrea in 1890, there were issues about race and mixed-race children’s national identity, like Maddalena. In 1909, twenty years after the beginning of the colonial invasion of Eritrea, the Italian government began to discuss the transmission of Italian citizenship to the many mixed-race children who were born in the colony. These children, if recognized by their fathers, they could be Italian because of the jus sanguinis principle, meaning the transmission of Italian citizenship passed by blood. And many of them, like Maddalena, or like some members of my family, were going to Italian schools, their first language was Italian, they had an Italian culture, and they had Italian surnames, like mine. For these people their first identity was Italian. But then, like the women I interviewed who were born in Eritrea or in Ethiopia during Italian fascism and colonialism and moved to Italy in the 1970s thinking that they were Italian – when they arrived in Italy they went through a big shock. They came by plane or by crossing the Mediterranean with an Italian passport in their hands, nothing to do with the terrible journeys that many Eritreans undergo today. Upon arrival they are not recognised as Italians by white Italians and they are called racial slurs. They went to Italy thinking of going to a second motherland to discover their history did not exist anymore. In the 70’s Italians had forgotten about the colonial past and many of my respondents were asked where Eritrea or Somalia was located or how they would speak such a good Italian. This demonstrates the complexity of Italian history and the formation of national identity. Italy, still today, pretends to be a white country, while its connections with blackness are historically rooted and they are very ancient.