Global Dimensions will be taking a short break, but we’ll be back in 2017 to continue bringing you stories from around NYU’s global network.

Wishing all happy holidays, and a peaceful New Year.

Global Dimensions will be taking a short break, but we’ll be back in 2017 to continue bringing you stories from around NYU’s global network.

Wishing all happy holidays, and a peaceful New Year.

Gary Slapper, NYU London’s beloved Site Director, and an NYU Global Professor, passed away on Sunday after a brief and sudden illness.

“Gary was one of the first members of the NYU community I came to know, and we have not only lost a great site director, but also someone of great humanity,” said NYU

President Andrew Hamilton. “Gary helped to build London into one of NYU’s premier sites with grace, attention to detail, and of course, a sense of humor that was second to none.”

Gary was named Site Director in 2011, after serving as director of the Open University’s Centre for Law. During Gary’s tenure, NYU London experienced a nearly fifty percent increase in enrollment, with more than 1,000 students studying at the site each year, and the site expanded its academic breadth to include disciplines such as education, public health, and fashion.

“Gary was a cherished member of the NYU community,” said Linda G. Mills, Lisa Ellen Goldberg Professor and vice chancellor for Global Programs and University Life. “His commitment to NYU’s students, lecturers, and administrators was at his very core, closely rivaled by his sense of humor and great intellect, all of which brought smiles as well as keen insights on a daily basis. We are all in shock that such a rich and generous life has been extinguished far far too soon.

Gary was a true renaissance man, nimbly switching between law, philosophy, football, the environment, and pop culture (with The Simpsons holding a special place in his heart). He was also an accomplished writer, penning The Times [of London] Weird Cases column, in which he explored particularly strange legal cases, bringing immense entertainment to his readers – and we think it’s safe to assume, to Gary himself.

“Rarely can a ‘boss’ have been a more popular and revered figure,” said Eric Sneddon, associate director, NYU London. “We all recall a man of warmth, great humor, gifted at once with a razor sharp mind and a common touch. The university has lost someone truly special; anyone who moved within Gary’s orbit would feel enrichened and would know the world is now poorer.”

A graduate of University College London, Gary received his Ph.D. from the London School of Economics. He was the author of some 15 books concerning law and the English legal system, and was also a visiting professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The NYU community extends its deepest sympathies to Gary’s wife, Suzanne, his three daughters, Charlotte, Emily, and Hannah, and the rest of his family, friends, and colleagues, in the UK and beyond.

Read More:

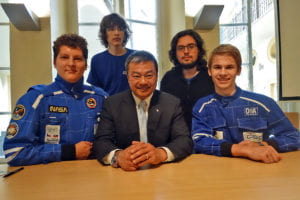

Leroy Chiao, an American astronaut who has spent 229 days in space on four separate missions, presented his newly-published book, Make the Most of Your OneOrbit, to a packed audience at NYU Prague in October. The book, published by Zdeněk Sklenář Gallery, with the cooperation of NASA and the Chinese Authority of Flights of People into Space, is a collection of photos taken by Mr. Chiao, selected from the more than 16,000 images he shot from the space station between 1994 and 2005.

Leroy Chiao, an American astronaut who has spent 229 days in space on four separate missions, presented his newly-published book, Make the Most of Your OneOrbit, to a packed audience at NYU Prague in October. The book, published by Zdeněk Sklenář Gallery, with the cooperation of NASA and the Chinese Authority of Flights of People into Space, is a collection of photos taken by Mr. Chiao, selected from the more than 16,000 images he shot from the space station between 1994 and 2005.

Chiao first decided he wanted to become an astronaut at the age of eight, when he saw Apollo 11 land on the moon, and he wondered whether it was possible to capture an image of the Great Wall of China from space.

“One of the great myths is that the Great Wall of China is the only man made object that is visible from space; I spent a lot of time with my telephoto lens trying to take a photo of it,” he said. “I didn’t see the wall myself – I saw many lines in the mountains, but I couldn’t tell which was a wall, a road or a riverbed. I think I can say that no astronaut has identified the wall with his or her bare eye.”

Audience questions, not surprisingly, focused on what it was like to be in space. “The first time I flew into space, I thought I knew what to expect – I had seen movies, talked to astronauts- but the first time I looked at the earth from space was very emotional,” said Chiao. “The colors were much brighter than I expected – It made me feel wonderful, joyful. It also made me feel small.”

What about his thoughts on science fiction flicks? “I check my engineering hat at the door when I watch films about space,” he said. “There are a lot of technical errors, but some films do capture the visceral fear that all astronauts have – whether we admit it or not.”

Future of the space program

Mr. Chiao, who was on a White House committee to review NASA policy, also discussed his belief that international cooperation is crucial to further development of the space program with the international space station as a symbol of how countries can work together. “Whenever we have new astronauts come onto the space station, we greet them using a Russian tradition – giving them bread and salt,” he said. “But we use salt water so crystals floating around don’t get in our eyes.”

OneOrbit was first published in Czech and will soon come out in English and Chinese. The book was the brainchild of Czech gallery owner Zdenek Sklenar who befriended Mr. Chiao in 2009. The astronaut – who says he is an engineer, artist second – said that this book “brings together the universal values of art and rationality.”

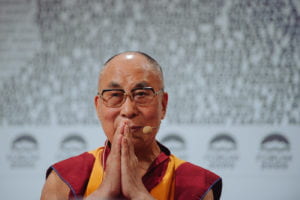

October 2016 marked the 20th anniversary of the Forum 2000 Conference, founded by former Czech President Vaclav Havel to support the values of democracy, respect for human rights, assist the development of civil society, and encourage tolerance.

NYU Prague has long had close ties to Forum 2000, as Jiri Pehe, director of NYU Prague, was chair of the program committee for ten years, and many NYU Prague professors currently act as organizers and delegates in the program. Building upon these connections, NYU Prague students have the opportunity to participate in the conference, gaining access to world-renowned politicians, activists, academics and journalists. Students can also apply to intern for the Forum.

This year, NYU Prague students had the chance to hear His Holiness the Dalai Lama – Nobel Laureate and an exiled Tibetan spiritual leader – speak about compassion in world politics, as well as dozens of other world leaders discuss the conference topic: The courage to take responsibility.

This year, NYU Prague students had the chance to hear His Holiness the Dalai Lama – Nobel Laureate and an exiled Tibetan spiritual leader – speak about compassion in world politics, as well as dozens of other world leaders discuss the conference topic: The courage to take responsibility.

Anand Balaji, a finance/economics major in Stern Business School, interned at this year’s Forum. “It was an incredible event that I never in my wildest dreams thought I would get access to as a sophomore in colleg,” said Balaji. As part of his responsibilities, Balaji reported on a panel about the philosophies of Havel and Gandhi, and also met Philip Zimbardo, psychologist and the leader of the Stanford Prison experiment.

Petr Mucha, professor of religious studies at NYU Prague, and member of the Forum 2000 program committee, invited his students to attend the Dalai Lama’s talk. Reilly Hilbert, a double major in religious studies (CAS) and acting (Tisch), shared her experience.

“We must make earnest of love and compassion in secular education. Not tying it to the next life, to heaven or hell, but to the present, with the understanding that harmonious living can only be achieved under compassion” —His Holiness the Dalai Lama

I am sitting in a white room in a very modern building, across the way from a very old building, on a small island in Prague. I am twenty minutes early and sweating because it’s not quite cold enough for my big coat, but too cold for my smaller one. I’m sitting in the second row, to my left is a political leader of a country of 46,000 discusses with two of his colleagues the reality of Trump’s systematic lies. To my right, a woman from India, hands folded, head down, mouth moving in what I think is a prayer. The Dalai Lama enters, everyone stands, and he shakes hands with people in the first row, and when he gets to my end, he sees the woman to my right and reaches out to her, over the bodies of the first row people. They exchange a few words, and she says, “Thank you for your blessing.” He waves at me, I smile and wave back, feeling both very big and very small at the same time. The woman next to me says, “He knows I’ve been praying for this.”

Praying for this. I am Catholic. I am a Catholic woman negotiating being also an artist, activist, actor, student, daughter, sister, friend and girlfriend in the 21st Century. It is painful, it is difficult, and I frequently find myself searching for truths in Religious Traditions that are not my own. In this way, the Dalai Lama let me down. His mission is Love, his mission is Compassion, Unity, and Togetherness. And where have I heard this before? In every homily, on every retreat, and in every meditative prayer I have had the opportunity to hear, see, and do. On every Krista Tippet On Being podcast, in every one of the numerous books that I’ve read about the potent experience of Religion—be it Catholicism, Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, or Buddhism, I have heard the same word: Love. And as I sat five feet from one of the Holiest men alive right now, I was disappointed to hear it again. Instead of feeling fulfilled and alive because of this ever present notion of love that surrounds me in everything I have been given the opportunity to do, I was sad that there wasn’t some magical new way of connecting to the world. As I continued listening to the other speakers, I worked to identify where this seemingly unfounded pain came from.

Tarek Osman, author of the popular book Egypt on the Brink, and another panelist in the conversation with His Holiness, helped me investigate this dissatisfaction. Osman said that “Religion can put forward order, but there is a very thin line between order and control.”

Tarek Osman, author of the popular book Egypt on the Brink, and another panelist in the conversation with His Holiness, helped me investigate this dissatisfaction. Osman said that “Religion can put forward order, but there is a very thin line between order and control.”

I remembered, while he was speaking, the model brought forth by Stephen Bush of religion as being essentially based in three things: power, meaning, and experience. The Dalai Lama’s notion of boundless love, compassion for all people, is all well and good, but Osman also grapples with negative aspects of the power religion has.

Catholicism for me has been very powerful, in both positive and negative ways, and it can be difficult to sort out. So the fact that love can seemingly be used however it best works for people does not fit in the binary that instilled love in me in the first place. If religion can be used as a tool to harm in the name of love, it can be placed in a binary “evil” category. But if religion is only a source of “light and love,” it might be “good” but it disregards the evils present in societies today that are carried out in the name of religion. This is where the unrest began to clarify itself.

The third panelist, Daniel Herman, the Czech Republic’s Minister of Culture, spoke about the crisis of modernization, explaining that post-Communism, he finally understood the Jewish Exodus. It took 40 years to renew, it took several generations to reestablish, and it was not only a physical renewal, but a moral one. He explained that the Czech Republic is only in year 26 of its own “Exodus,” and said that many societies today are in the middle of their desert.

In the United States, he added, Americans are still in their own desert, coming out of slavery, World War 2, Vietnam, and the women’s rights, civil rights, and gay rights movements.

And maybe that is why love is so difficult for me, because in my binary brain, love should be easy, natural, and something we can just do. But I know better than this. I know love is actually the most difficult thing in the world. It goes against the tendency to compete, to overcome, and to win. It goes against the tendency to control, to possess, and to know. Loving is not knowing. Loving is learning, it is hoping, it is working, and it is hard.

The Dalai Lama also said we need to be more active in love. We need to strive for teaching love in secular education, because love, though incredibly difficult, is a universal idea. And love is what will bring us out of our deserts. Not romantic love, not familial love, but a love for humanity that is so often forgotten in our world of immediate gratification and confusion.

The Dalai Lama said, “When I lived in isolation in Tibet, Buddhism seemed the only way, then I went to India.” There is not one right way to negotiate love. There is not one path. And this recognition of unity beyond objectivity is what can open us to love in all its difficulty. I’m praying for this.

I want to say thank you to Professor Mucha for giving me the opportunity to attend this conference, as Religious Studies is not only my major, but also very close to my heart, and so I feel grateful not only for the learning experience, but for the personal growth it helped me obtain.

Photos taken from the Forum 2000 website here.