Part 1: The Principles of Aesthetics

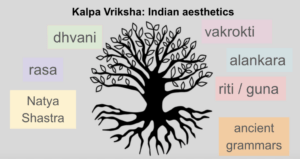

The Sanskrit theoretical tradition, in general, commonly uses the figurative idea of the kalpavrikSha. This is a mythological gigantic tree which grows in the world of the gods and fulfills all the wishes of the mortals. It is depicted with deep roots, trunks, branches, leaves and flowers. The terminological meaning can be interpreted as the tree representing the structure of the object of cognition, which means it is a developed theoretical system. The roots, the trunk, the branches, the leaves and the flowers symbolize the different levels and elements of this structure.

Let me try with you an experiment. Let us try to imagine that the kalpavrikSha can be used as a concept map to organize our understanding of the what we call in English Sanskrit theory of poetry or Sanskrit literary theory, and in Hindi this is alaNkaar shaastra, sahitya aalochna, sahitya sidhhaaNt, kaavya shaastra, etc . Anyway, this is a broad field where philosophers define the aesthetics of literature and art. Moving back to the experiment — kalpavrikSha — the roots of the tree are the treatises of the Ancient Indian grammarians. They introduced foci of analysis and concepts which later became central to the literary theory of Ancient and Medieval Indian scholars. Consequently, these roots gave the beginning to the tree trunk – this is the first comprehensive work on dramaturgy – the Natya Shastra put together by the sage Bharata (Note: I am using the phrasal verb ‘put together’, since I want to be careful and take into account the fact that today we don’t know for sure whether he is the sole author, or what and how much he inherited from the tradition before him.) The old linguistic concepts are re-interpreted at a functional level — they are examined beyond their grammatical role, but from an aesthetic point of view or what they create and how they are received by the spectators. Let us not forget that the language of the drama, written and performed, was in meter, i.e. it was poetic in its nature. Therefore, this massive, encyclopedia-like work with no similar example anywhere in the world offers several innovative ideas, which drew the attention of contemporary and later theoreticians. Thus, if envisioned as part of the trunk of the tree, these ideas serve as the principal foundation for the further development of the Sanskrit poetological knowledge or aesthetic theories, which refocused on the production and reception of poetry – at that time the only form of written artistic production (possibly because of the long standing tradition of orality in intellectual production and communication as well as transmission of knowledge).

So far, we have envisioned the roots and the trunk of kalpavrikSha, however, what do the branches of the tree represent? The main question, which Sanskrit literary theoreticians were interested in, was how to define what poetry is, what its main principles (lakshaNa) or meaning (arth) are, or what the essential elements are that make poetry different from other types of speech. To some scholars it was the ornaments (alaNkaara), for others – it was the unusual speech (vakrokti) and, yet, there were those who insisted on the idea of the aesthetic experience (rasa). Furthermore, many considered suggested meaning (dhvani) to be the defining principle and so forth. In search of such answers the different schools (sampraday) started, branched out and proliferated. We will discuss these concepts in what follows here.

It is difficult to pinpoint the century when the literary theoretical tradition emerges in India. Therefore we can start with the first written document that has come down to us or the first visible part of the tree, the trunk – this is the Natya Shastra by the sage Bharata. The tradition also call it the fifth Veda. Most probably it was assembled sometime between 1st and 4th AD. It includes all aspects of knowledge and experience related to drama and theater. It consists ofabout 36 chapters on the following topics: theater building architecture (chapter 2), music (chapter 4), make-up, costumes, and stage decor (chapter 21), dance (chapters 28-34), the art of gesture and mimics (chapters 9-12), the 10 types of the drama genre (chapter 18), methods of developing, expanding and modifying the plot (chapters 19, 20, 23), the types of heroes and heroines (chapters 22 and 24), details about the credentials, qualifications and the duties of the actors (chapters 25-26) and most importantly analysis of the poetic language used in the plays, including in the dialogues and the types of poetic verses sprinkled throughout the text (chapters 13-17).

In other words, the theoretical field of poetics has its beginnings in the realm of drama, because the ancient philosophers consider drama not just a spectacle (tamaashaa), but also as a textual entity which generated an unique aesthetic perception and experience (rasa). Therefore, the idea of rasa can be considered the first branch of the tree – it was introduced and developed in the Natya Shaastra for the first time. This concept defines the future development of the Sanskrit theory of poetics and of the aesthetic tradition of art until today. Rasa means ‘juice’ or else ‘ life-giving liquid’, on the one hand, and on the other hand it means ‘invigorating power’, and, moreover, it means ‘taste’. This is a very unique multi-faceted term related to the aesthetic experience of the audience while watching a play, a dance or poetry performed on stage. Rasa is the a discrete and defining principle of the poetic speech; it is also the object of the audience’s taste, as well as the process of impression, reception and enjoyment caused by the object of aesthetic experience.

Bharata puts forward the claim that the drama is based on ‘imitation’ (anusaraNa). This idea is very similar to Aristotle’s one about ‘mimesis’. But the similarities are actually superficial. According to the Greek philosopher imitation refers to the action which happens on stage to draw the attention of the audience towards the plot, whereas the Sanskrit theoretician has in mind something different – that imitation is pertinent to the mental and emotional state of the audience while watching the performance. He mentions that there are transitional emotions at the moment of reception (vyabhicaribhava), which accompany the steady or permanent emotions (staaiibhava), which are experienced by the members of the audience in their everyday life. These emotions are activated by being imitated during the performance on stage and thus the spectators undergo an aesthetic experience rasa. This is to say that emotions (bhava) belong to the real world life, and the aesthetic experience (rasa) is a result of the artistic performance or art, which includes literary texts as well. This theory remains popular among the Indian literary theoreticians at least until the second half of the 10th century, when the philosopher Abhinavagupta further expands this school. He places emphasis singularly on the receptive end – the audience’s reception of the art. There are several types of rasa according to this school and they are evoked by specific triggers in language and stage performance. Interestingly, this school reminds us of the 20th century emotive theory of art which inspired many poets and writers who are considered a part of the European Romanticism.

The second big branch of the poetological kaplavrikSha is the ‘ornament’ or the ‘embellishment’ (alankaara), which represents the most essential principle of the poetic language. The so-called alankaara shastri analyze poetry at two different levels: one is at the level of the linguistic fabric or the ‘body’ or the specific use and placement of the words, which reveals the author’s intent and objectives, and the second layer is the beauty of the poetic language or the ornaments which captivate and mesmerize the audience. This type of analysis to poetic language we find in the Natya Shastra, but the treatise “The Mirror of Poetry” or Kavyadarsha by Dandin, who lived in the 7th century AD, is a great example of the effort to further expand this theory. It became popular across the subcontinent up to Nepal, Tibet and Mongolia, where its tenets defined the poetic theory and production for centuries. The ‘ornaments’ (alankaara) are classified into three types. The first category is word-based (shabdaalnkaara) defined by specific acoustic and rhythmic properties. The second group consists of meaning-based (arthaalankaara) ornaments which are built on the basis of the functional and semantic relations of their components. Examples of such relations are first of all the category of similarity, which consists of simile, metaphor and repetition; another one is the exaggeration, which is comprised of cause, negligence of similarity, hyperbole, etc.; a third one is the controversy which includes coincidence, negation, etc. And the third type are the mixed ones, combining both set of characteristics.

Ancient European philosophers were concerned with very similar figures of speech, e.g. Quintillian in his Institutio Oratio. However, since they were interested in the field of rhetoric, they had in mind a different objectives – the main goal of the orator in regards to the audience was to captivate it (lat. delectare), and to move it (lat. movere) in order to convince it (lat. docere). Therefore, this last objective of the Latin orators was in a way limiting the use and the function of the figures of speech in order to ensure direct understanding in the context of the speech. The Indian philosopher Rudrata, who worked in the first half of the 9th century, claims that the main goal of the poet is to mesmerize or charm or enthrall the audience and that this is achievable by the creation and use of ornaments (alankaara) that contain a high degree of suggestive meaning and without it they cannot exist. They make the poetic speech polysemantic and they can even change its general context. It is for this reason that the rich mythological and cultural setting of Ancient and Medieval India creates an extremely rich associative background, which make it possible for a text to acquire multiple layers of meanings and, hence, interpretations.

Consequently, the Sanskrit poetological thought gives importance to the process of creation and re-creation of the indirect or hidden meaning, which eventually becomes an independent branch – the theoretical model (dhvani) put forward by the theoretician Anandavardhana in the 9th century AD in his work The World of Dhvani (dhvanyaloka). He analyzes three main semantic layers or three meaning of the word when used masterfully in poetry: the primary or direct (mukhyartha), when despite the context or other means the referent is clear; secondary or transposed (gauniartha), when the primary meaning is expanded due to some kind of a connection established with the first meaning usually by association or similarity, namely because it creates metaphoric or metonymic connections, etc.; the third one is the suggestive meaning (dhvani), when the intended hidden meaning is revealed. The difference between the secondary and suggestive meaning is the first one can be transformed completely and changed, whereas the second one preserves the indirect meaning and adds a new one. In addition, according to Anandavardhana, the secondary meaning is based on the word itself and it encompasses some kind of concept or piece of reality (vastu), whereas the suggestive meaning can also encompass an alankaara or rasa. The most intriguing part of this theory is that the cognitive perception of the text creates the secondary meaning, but the suggestive meaning remains in the realm of the aesthetic experience. This three way division reminds us of the ‘sign-signifier-signified’ concept that Ferdinand de Saussure introduced to the European philosophy and linguistics in the end of the 19 and beginning of 20th century and spearheaded the Structuralism movement.

Another important branch of the tree represents the school of values (guNa) or style (riti) proposed by by Bhamaha who lived in the 6th century AD and Vamana from the 8th century AD. They furthered the idea of rasa by developing the many ways it can be expressed – for example though ‘sweetness’ of speech (madhurya), ‘splendor’ (ojhasa), etc. On the other hand, the proponents of the stylistics approach drew parallels between the poetic language and the human body, in which each component is important because of its relationship with the rest, in the way that the combination of the individual components makes the beauty of the whole. In contemporary terms, according to linguo-stylistics the literary text is a living organism, which functions through the relationship of all its components.

The concept of unusual speech (vakrokti) as the main distinctive feature of poetry was introduced by Kuntaka who lived in the second half of the 10th century AD. This branch is based on the assertion that poetic language is figurative and associative in its essence, because it breaks the rules of everyday speech. This in contemporary terms relates to the Russian Formalism and its idea of ‘ostranyenie’ or ‘defamiliarization’ or else distancing because of the unusual features of the poetic speech. Simiarly, the Polish structuralists claimed that poetic language exercises violence over the rules of the grammar of regular speech to create a special effect that the other types of speech cannot do.

Another branch which chronologically developed most recently compared to the rest of the theories is the appropriateness theory (auchitya). This is the fundamental principle which functions at the level of the phoneme, morpheme, lexeme, even at the level of a whole speech, including rasa or alankaara. Appropriateness or suitability is needed to touch the audience’s heart and to enrich their inner world.

Divine Speech started the Universe according to an old mythological narrative. In other words, the universe emerged from Speech, then humans were born and they started learning and mastering Speech. This is why in India it is considered a supreme talent to be in control of poetic speech and thus to be able to influence the human emotions, psyche and creative imagination. No other culture has such an elaborate system of concepts related to poetic speech, literary production and reception!

Readings and questions to explore further

Part 2: Medieval Poetic traditions in the North

The Bhakti movement, according some accounts, started as early as the 6th—7th century in the South, where a Tamil-speaking group of non-brahmanical Vaishnava poets described their intense love to God along with their pain from being separated from God. Kannada poets and poetesses advanced these ideas along with a newly emerging social awareness directed against caste hierarchies within the Hindu traditions. This reformative school gradually spread, became popular and flourished in the North, which,, currently is what we focus on.

Many are familiar with the Gitagovinda. It is a beautiful poetic composition in Sanskrit authored by the poet Jayadeva in Orissa in the 12th century. The lyrical poet is deeply inspired by his devotion to and love of God and he represents Krishna’s relationship with his beloved Radha as a religious, aesthetic and erotic experience. The music Krishna played on his flute was so captivating and intoxicating, that all the cow-herding girls would flock toward him and dance with him, while he magically appeared next to each one at the same time. This dance, called raslila is viewed as a symbol of the follower’s pure devotion to God, a symbol of the personal and direct relationship between the individual and the Supreme Being. The Gitagovinda became instantly popular in dance and song. (See for more Barbara Stoler Miller. “The Devine Duality of Radha and Krishna”. The Devine Consort: Radha and the Goddesses of India. Eds. Hawley, J .S. and D. M. Wulff. Motilal Banarsidas Publishers, 1995. Pp. 13-27.).

The reason why I draw your attention on this poem is because it is one of the quintessential works of the Bhakti movement, this newly formed mystic-philosophical school that advocates the intimate and personal loving relationship between the individual and the deity, irrespective of age, gender, language and caste and, most importantly, without the mediation of priests. It is extremely important for us, because, afterwards poets started gradually using more and more the language for everyday communication or the local vernaculars, rather than Sanskrit.

Around the 15th century one of the most unique poets of India wrote his religious-philosophical poetry in the vernacular spoken in the area of Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, a mix of Bhojpuri, Braj and Avadhi, instead of in Sanskrit, because it was becoming too complex and incomprehensible for the common people. Everyone is familiar with the name of Kabir. He was born in a Muslim family but grew up in a Hindu setting. Thus he is considered by many to be a universal guru, revered by Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Sufis. He is a mystic who retained the idea of rebirth and karma, but objected to caste-based social hierarchy, idol-worship and pilgrimage. Kabir promoted full devotion and pure love to God, who is envisioned in most abstract and non-anthropomorphic terms. Kabir is venerated by the Bhakti movement and is recognized as the founder of the nirguuNa branch or ‘with no-attributes/qualities’ branch. Kabir is also highly esteemed by the Sufi mystics within the Islamic tradition, who supported the principles of asceticism and self-devotion not as a result of fear of punishment or expectation of reward. His ideas were also an inspiration for a new religion, Sikhism, whose holy book Gurugranth includes a great number of his verses, according to which moral purity and discipline is the way to unite with god, in other words liberation.

The second branch of Bhakti is saguuNa ‘with qualities’. Most important work is Suur Saagar by Surdaas from the end of the 15th century, who devoted his great poem to Krishna and composed in the Braj vernacular to make it accessible for the lay people. Mira Bai also wrote around that time, but she is believed to have lived in Rajasthan. Later on, in the 16th century Tulsidas composed and wrote Raam Charit Maanasa in Avadhi and it became one of the most popular and influential works in the history of Indian literature.

However, it is necessary to underline the fact that poems in the vernaculars, specifically in Avadhi, existed even as early as the Ghaznavid period (circa 977–1186) and later on, in the regional pre-Mughal Muslim court. Most popular were the Sufi compositions, written in Avadhi (circa 1379–1545), which, although unexpected from our contemporary point of view, are a major part of the tradition. These so-called premaakhyaan or Sufi love stories continued to be performed long after they were composed. Not only are Avadhi poets known to have made compositions in Avadhi under the patronage of Shah Sur, but also members of the local nobility themselves composed in Avadhi themselves.

As a result, writing in local dialects flourished in the 16th century and remain dominant for a while. It is important to consider that the atmosphere of tolerance established during Akbar’s rule played some role in the spread and growth of Bhakti as a literary, religious and social movement. In other words, as Rupert Snell has put it: “the combination of Muslim-dominated political structure with largely Hindu populace fostered a cultural symbiosis which was richly productive in the interconnected realms of music, art and literature.” (The Hindi Classical Tradition: A Braj Bhāṣā Reader, p. 33). As Busch claims, especially since the Braj language was very similar to the dialect spoken around Agra, it must have been readily comprehensible to the Mughals, and, even if Persian would always occupy the position of highest prestige in the hierarchy of Mughal literary forms, an impressive list of emperors as well as members of the Mughal nobility also sponsored the production of texts in local vernaculars,. (“Hidden in Plain View: Braj Bhasha Poets at the Mughal Court”, Modern Asian Studies 44, 2, 2010, pp. 267–309.).

Gradually the two vernaculars were elevated to the status of highly regarded languages of court poetry composition: Avadhi, which was used and originated in the eastern parts of the subcontinent and Braj, used in the north and north-west, although these geographical delineations are quite relative. Subsequently, irrespective of the local dialect of the composer the two languages started being used consistently for artistic expression, including in the courts of the royalty and nobility, and they also became the languages of poetic creativity outside of the devotional, but in the romantic and aphoristic realm, i.e. they were employed in secular contexts. The languages are mutually comprehensible and quite similar, in spite of certain morphological differences. What we are concerned with was that they can both be classified linguistically as Hindi or early Hindi (which was often called ‘Hindavi’). With time, Braj gradually superseded Avadhi not only for obvious socio-cultural and political reasons dictated by the popularity of local vernacular poetry and the growing interest towards this kind of literary expression and of the Mughal royalty and nobility and their patronage of local poets, on the one hand. On the other, Braj acquires a prominent status as a language of poetry for linguistic reasons as well. The most important one was that it adhered less to the Sanskrit language and hence it was more flexible in including borrowings from the Persio-Arabic lexicon. In addition, this gave way to tapping into the imagery and ideas of the Persio-Arabic tradition, which in turn made it comprehensible to and enjoyable by a much wider audience.

It is informative to trace the language use and preferences in the Mughal court. We need to start with Babur (r. 1526–1530), the founder of the empire, who must have spoken and written in Chagatai Turkish, the language he used to write Baaburnaamah (his autobiographical work). Next in the newly established Mughal dynasty is Humayun (r. 1530–1540, 1555–1556), who lived in exile for a while in the Safavid court in Iran and hence established the Persian as the elite language of his court, but he also acted as a patron to Turkish poets. According to several historical records, his son Akbar and his grandson Jahangir, were proficient in spoken Hindavi or Hindi, as were all future Mughal rulers. Driven by political objectives local Rajput kings their daughters as brides. The mothers of Akbar’s son Jahangir and grandson Shah Jahan were both Indian Rajputs. Thus, over the course of Akbar’s reign Hindavi or Hindi was in some cases literally becoming the mother tongue of the Mughal princes, even if Persian remained the primary public language, and ties to Turkish were maintained. The new types of song and poetry emerging from around Agra and Mathura must have been a natural subject of imperial interest. As Busch elaborates: “While Persian literary patronage proclaimed the Mughal rulers’ rootedness in a cosmopolitan Islamicate world, listening to Braj poetry and music was a means of engaging with the local. This would have been at once a political and a cultural choice.” ( “Hidden in Plain View: Braj Bhasha Poets at the Mughal Court”, Modern Asian Studies 44, 2, 2010, pp. 274-275.).

Many Braj poets who were well known during their time are, unfortunately, some are little known today because of lack of records. They produced beautiful poetic works adhering to the conventions of the riiti sampradaay or the stylistic approach to poetry. This branch, which we touched on in the previous lecture, places artistic emphasis on the specific linguistic and rhetorical features of the poetic text. These Braj poets also wrote treatises on poetics, where they demonstrated their talent through the creation of poetic examples of remarkable quality, highly valued by patrons and pundits alike. In addition, many writers innovated beyond the established conventions thus creating this rich and pervasive philosophical, artistic, social and religious phenomenon. Some of the names we know are Shiromani, Biharilal, Sundar, Gang, Keshavdas, Abdur Rahim Khan-i Khanan, etc. One of them is also Kavindracarya Sarasvati, a Maharashtrian thinker and poet, who praised in his poetry the unique scholarly qualities or we could also say socio-linguistic competence of the emperor Shah Jahan in the following way:

Kuraana puraana jaane, vedani ke bheda jaane etii riijha etii buujha aura kaho kaahi haN Sumera ko sauno deta, diina dunii dono deta

He knows the Quran and the Puranas, he knows the secrets of the Vedas. Say, where else can one find so much connoisseurship, so much understanding? He gives a Mount Sumeru worth of gold, he gives this world and the next. (Cundavat (ed.), Kaviindrakalpalataa 1958, p. 4, v. 8).

We should always keep in mind how multilingual, multilayered and multifaceted the cultural milieu was during the Medieval period. Moreover, and when we are delving into the history of Hindi and other language literatures, we should never forget that the Bhakti movement was never homogeneous or uniform. Therefore, making any generalizations would be a serious misrepresentation of its complexity. However, this does not preclude us from searching for the underlying aesthetic principles of the pre-colonial literary writings rooted in the Bhakti tradition of love and devotion.

Readings and questions to explore further

Part 3: When is the birth of Hindi literature?

It is a far more complicated question than the birth of Urdu literature. The answer cannot be as easy as it is for example for Italian – Dante wrote the Divine Comedy in a spoken vernacular instead of in Latin and with this gave rise to the literary use of Italian, which therefore is considered its birth as a language. This is why Dante is considered the father of modern Italian. For Hindi, this is a very disputed question. Now that we are familiar with the main characteristics of the period called bhakti and riiti kaal, we have no doubt that the beginning of Hindi literature and certainly the Hindi language is not based on a specific moment in time, or one place, one event or one writer. It is a long, slow, gradual and complex process of several vernaculars co-existing together in a large geographical area as literary languages as well as languages for communication. All of them Braj, Bhojpuri, Avadhi, Rajasthani were mutually comprehensible used by Hindu and Muslim writers for Muslim and Hindu royal courts and audiences. Literature in the late Medieval period was still written in meter and verse; prose was not used extensively for artistic expression and probably was not considered yet aesthetically fit to perform this function.

An interesting and relatively new process, however, needs our attention which occurred at the end of the Medieval period – namely, this is the gradual decline of the Mughal courts and at the same time the gradual increase in volume and quality of poetry written in Urdu. On the one hand, Persian language was still in use for administrative and literary purposes, which was related to the Mughal identity of affiliation with the Islamic world. Hence, everything written in Persian followed the poetic conventions of that literary world. In spite of the fact that during the Safavi rule, when arts lacked royal support, and Persian poets moved to the Mughal courts seeking patronage there, the voices of the Indian poets in Persian, unfortunately, did not receive appreciation and serious scholarly attention in the Persian poetic circles. On the other hand, the 18th century is marked by the continuous decline of the socio-economic conditions in the big cities, such as Agra, Patna, Lucknow and Delhi. As a result, some poets started using Urdu, in order to expand their audience– they turned to the domestic audience, which was more engaged and stimulating than the international audience they wrote for beforehand. Furthermore, the Urdu language gained popularity for two main reasons, one is because the poets were interested to address socio-political issues at home, which in other words formed themes outside of the love theme traditional for the Persian poetry. Hence, according to Fritz Lehmann’s article “Urdu Literature and Mughal Decline”, the most important factor was that the matter in question inevitably evoked local imagery, reference and trope, which neither the Persian poetry had in stock nor could the Persian language express effectively. Therefore, it was a natural switch to write in another language – the one used for communication among the community, about whose life the poets were concerned. This linguistic change mirrors similar processes in the Ottoman empire, where Persian was substituted with Turkish, and in East Africa, Arabic was displaced by Swahili. Thus, Lehmann states, the adoption of a regional cultural identity in place of a universal Islamic one was not peculiar only to North Indian Muslims. (Mahfil, Vol. 6, No. 2/3 (1970), pp. 125-131).

At the same time, we need to point out here that the so-called Khari Boli is the lingua franca spoken in and around the big cultural, political and economic centers in the North, including in Deccan. Urdu is a variant of this lingua franca, which is written in the Nastaliq, based on the Arabic script and whose lexicon was enriched with Persio-Arabic vocabulary. Thus it underwent a steady development and shaped up as the language for literary expression of social awareness in the hands of Muslim writers.

As we mentioned above one specific genre emerged as new compared to both Sanskrit poetry-based and Persian poetry-based traditions. It focused on aspects of the current socio-political reality of the poets which for the most part are processes of decadence, corruption and moral decay. In these poems, the writers address such problems of their city and its community with despair, pessimism and with a sense of despondency especially in the light of the glorious past of the Mughal kings. The most interesting poems are called shahar-e-ashob. Literally, this term means “lament for a city” and, as Lehmann claims in the same article, they have some vague antecedents in the Persian lamentations of the Mongol invasions in the thirteenth century. One of the first poets is Qazi Mahmud Bahri in 1700, followed by Muhammad Rafi Sauda, Mir Taqi Mir, Ghulam Husain Rasikh, Shah Ayat Allah Jauhri, Shaykh Wali Muhammad Nazir Akbarabadi, etc.

One of them Shah Ayat Allah Jauhri (1714-1796) who live close to Patna explained the current deterioration of values and moral as well as the political and social crisis with the state of Islam. In his poems he wrote: “Islam is an extinguished lamp, its light has gone out in every home” and “Muslims had failed to keep the faith, and their corruption brought on the inevitable retribution in the form of chaos and war.”

Nazir Akbarabadi (1739-1831) who lived in Agra, on the other hand, delved into the economic troubles of his time:

“Nowadays in Agra everyone is ruined. One can see at once that no one is prospering, Worthy men beseech refuge from such hard times; Those people are now one-cowry paupers, alas! Who know the techniques of a thousand different trades and professions.”

The famous Mir Taqi Mir (1722-1810) had the unfortunate fate, after he enjoyed living and writing in Delhi for many years, to be impelled to leave his favorite city and seek the patronage and the support of the Nawabs of Awadh in Lucknow. Mir criticized the state of the military power of the king and his court, the financial and economic depredation:

“Don't ask the condition of the soldiers. This one has pawned his sword, that one his shield. The Emperor and his Ministers, are all foolish.”[…] “A measly eight annas outweighs the king. His people have become wretched, He too, in fact, is similarly embarrassed, His army is killed by hunger, He himself is dying, with his family and household”

(Excerpts from Fritz Lehmann, “Urdu Literature and Mughal Decline. Mahfil, Vol. 6, No. 2/3 (1970), pp. 125-131)

At the time when Urdu poetry was an established part of the artistic ambience of the North, Braj, Avadhi and Rajasthani continued being used for poetic production yet more limited than before. The Khari Boli dialect was used in the poetry of Khusro (1256-1325) who is considered the first poet of Khari Boli. Scholars find his poetry closer to Sanskrit and Hindi prosody than to Urdu and Persian, i.e. his metrical and rhythmical patterns followed the poetic forms in Sanskrit, in spite of the occasional use of Persian words. In addition, Khari Boli was used occasionally and by no means to a limited extent by several other poets Kabir, Nanak, Dadu, Gang, etc.

Some limited and sporadic prose writing in these languages was done as well, mostly attributed to followers of the famous yogi-guru Gorakhnath (circa 11 century) and the bhakti guru Vitthalnath (16 century) in Braj, however, scholars agree these writings were non-consequential and did not spur any further development of prose tradition. The poet Gang from the court of Akbar wrote a story in Khari Boli but it also remained largely unnoticed by the writers’ circles of its time and the later period as well. Barannikov explains in his article “Modern Literary Hindi”, the failure of prose writing before the 19th century with the consistent use of Sanskrit by the thinkers of that time. (Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 8, No. 2/3, Indian and Iranian Studies, 1936, pp. 373-390).

Because of all that, what is important for us to remember is that up to the nineteenth century the spoken lingua franca Khari Boli was to a certain extent stabilized by its literary form, namely Urdu. Furthermore, Barannikov has put forward an interesting claim that Urdu prevented Khari Boli from splitting up into a number of dialects and hence has direct influence on the development of this language. He supports his claim with the fact that the first writers in Khari Boli although separated geographically wrote in the same language. (Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 8, No. 2/3, Indian and Iranian Studies, 1936, pp. 373-390).

One of them is Insha Alli Khan, who came from an Urdu speaking background and was a poet himself. He wrote a small story “raani ketkii kii kahaanii” in the Hindi language, as he wrote in the introduction, which seems to have been spoken by the educated circles. The style was simple, playful, vivid, full of verbs and lots of metaphors. It was almost like a literary experiment. By the time this story was written the East India Company was already settled in Bengal and the junior civil servants needed to be educated in the local language which they realized is not Persian but Hindustani and that they needed to learn it along with the Devanagari script. Pundits were appointed to prepare teaching materials and as a result the existing popularly used Khariboli underwent some form of Sanskritization. Lalu ji Lal was one of them, who was commissioned by the Administration of Fort William college and who wrote as he himself testified in the dialect spoken around Delhi and Agra, translated texts from Braj and Sanskrit. However, he lacked academic depth and solid knowledge. Another noteworthy writer is Munshi Sadaasukh worked independently and he translated the Bhagavatgita in prose in a very similar style and entitled it “Sukhsaagar”. Records show that the Muslims have called Hindavii, Hinduii, Hindii the dialect Khari Boli which has become the foundation for the so-called Hindustani style.

McGregor suggests that the missionary work in the early 19 century stimulated the dissemination of this new style through translations and reprints of the New testament. He also mentions that this process was further supported by the materials printed by the School Book Society of Calcutta and by the decision to teach Hindi along with Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic in a college in Agra in 1838. (“The Rise of Standard Hindi and Early Hindi Prose Fiction” The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland No. 3/4 (Oct., 1967), pp. 114-132).

Bharatendu Harishchandra is considered the first great writer of the Hindi language.