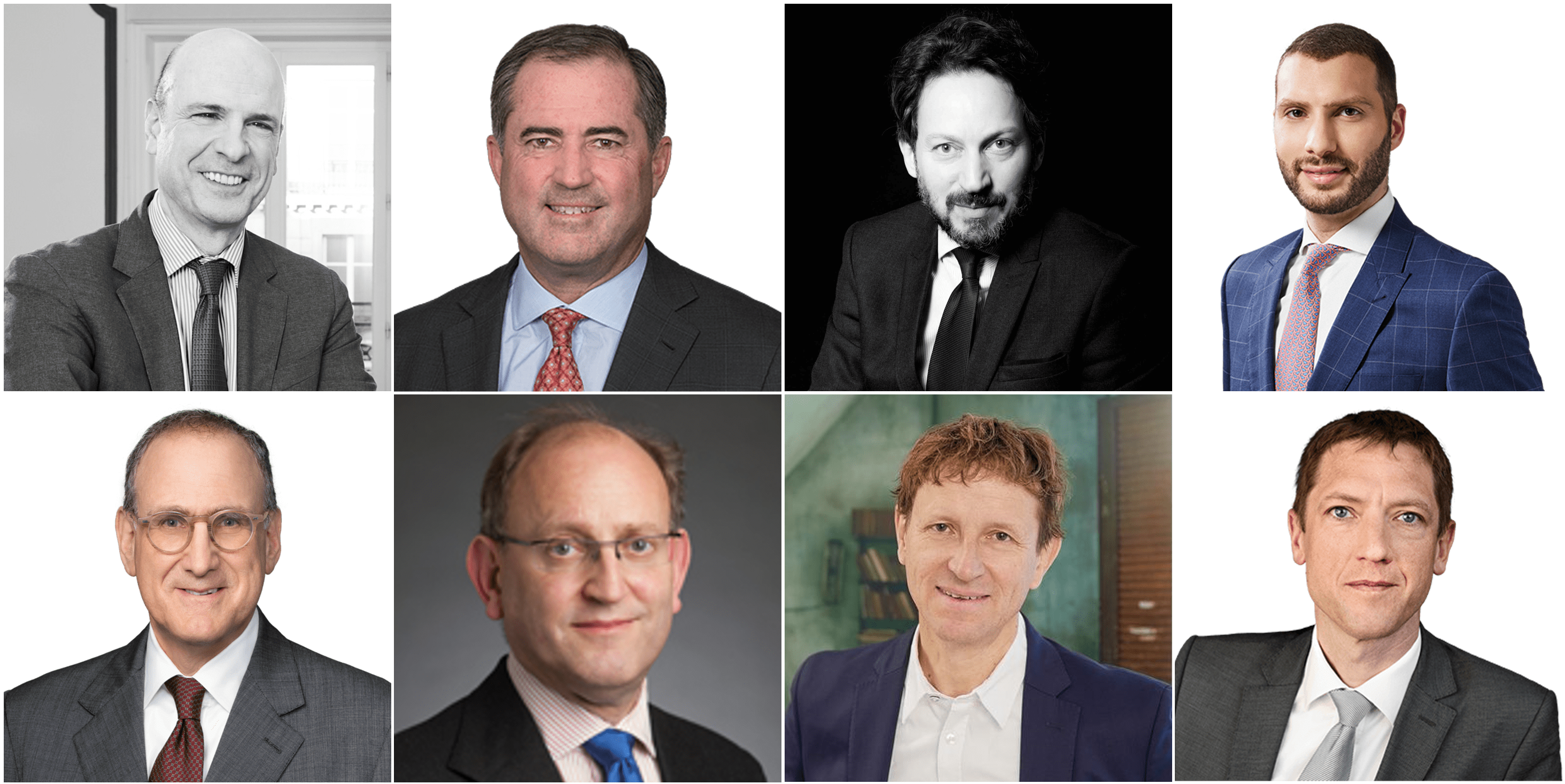

by Stéphane Bonifassi, Lincoln Caylor, Grégoire Mangeat, Léon Moubayed, Jonathan Sack, Andrew Stafford K.C., Wolfgang Spoerr, and Thomas Weibel

Top left to right: Stéphane Bonifassi, Lincoln Caylor, Grégoire Mangeat, Léon Moubayed. Bottom left to right: Jonathan Sack, Andrew Stafford K.C., Wolfgang Spoerr, and Thomas Weibel. (Photos courtesy of authors)

Introduction

Negotiated settlements for financial crimes offer a practical approach to resolving cases without lengthy trials. However, they pose a complex dilemma: how to balance efficiency with the need for victims to have a meaningful role in the proceeding and achieve adequate victim compensation. Across various jurisdictions, the approaches to non-trial resolutions reflect differing priorities, with some countries leaning towards expediency and others emphasizing victim rights. This is why the International Academy of Financial Crime Litigators published a working paper on the topic. This piece explores the current state of how victims of financial crime are being compensated in non-trial resolutions across different legal jurisdictions. Furthermore, it identifies some of the challenges and trade-offs lawmakers face when trying to infuse an optimal amount of victim involvement into the settlement process, providing suggestions on how victims of financial crime can be better heard and compensated in settlement procedures.

Victim Participation and Rights

Many jurisdictions strive to incorporate victim participation into their non-trial resolution processes, albeit with varying success. These efforts aim to ensure that victims are heard and compensated, but they can often be nerfed by restrictions in the interest of competing variables, like efficiency.

France’s Judicial Public Interest Agreement (CJIP) is an example of an attempt to balance efficiency with victim rights, although ultimately leaning more in favor of efficiency. CJIP, equivalent to a Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA), is an agreement between the public prosecutor and a legal entity. The CJIP process includes a requirement for the accused to set up remediation programs under the supervision of authorities, which can benefit victims indirectly by promoting corporate reform. However, direct compensation to victims remains a challenge.

Victims are informed of the process and invited to submit statements to help ascertain damages within the CJIP. Although the CJIP provides for victim compensation when a victim is identified, the amount and terms in the agreement are ultimately determined by the prosecutor, and victims cannot appeal these decisions. The CJIP process, however, does promote offender cooperation and provide a role for victims in the process.

A similar example is Switzerland’s “abbreviated procedure” which allows the prosecution and the accused to negotiate a deal, which the court then reviews and approves. Victims can assume a strong position of power in the procedure by establishing themselves as “private plaintiffs,” which confers on them the right to consent or refuse the negotiated deal.

However, the victim’s role can be limited or expunged by restrictions. For example, victims must file their monetary claims within a short ten-day period. Moreover, the lack of specific statutory provisions for detailed victim participation means that the extent of victim involvement can vary widely based on the prosecution office handling the case. Nevertheless, victims can benefit from eliminating the need to initiate separate legal actions where the challenge of proving their case could lead to more risk.

Other jurisdictions have focused on prioritizing victim compensation, sometimes at the expense of efficiency. The United States has robust domestic laws that serve as a valuable tool for ensuring effective victim compensation. For instance, under the Mandatory Victim Restitution Act (MVRA), a court may order the payment of restitution to compensate victims for financial losses caused by the defendant’s criminal conduct. Moreover, the Crime Victim Rights Act (CVRA) affords victims the right to timely notice of court proceedings and the opportunity to be heard at key stages of the legal process. These policies and others like them in the United States create incentives for companies to remediate harm done to victims even in the absence of the filing of charges and a conviction.

Obstacles and Costs of Victim Compensation

Addressing victim compensation in non-trial resolutions introduces significant complexity and can come at a high cost. Many different frictions can arise that hinder lawmaker’s efforts to compensate victims. For example, identifying and compensating victims can be a challenging resource-intensive process that complicates the settlement and delays resolution.

Adding to the complexity, ambiguities in certain non-trial resolution regimes can pose significant challenges to victim compensation. In that context, one major issue is the enforceability of victim compensation terms within the settlement agreements. In some jurisdictions, there is uncertainty about whether failure to comply with victim compensation provisions would lead to significant consequences for the corporate offender. For instance, if a company breaches a compensation order, the mechanisms to enforce compliance might be unclear or weak, potentially leaving victims without the promised compensation. This lack of enforceability undermines the effectiveness of victim compensation efforts in non-trial resolutions.

Another challenge is the difficulty in defining who qualifies as a victim eligible for compensation under these regimes. Ambiguities in the definition of “victim” can result in inconsistent instances of compensation, where some affected individuals or entities might be excluded due to narrow interpretations.

Another important consideration in granting substantial power to victims in these proceedings is that it can lead to defendants facing higher-than-appropriate damages. Compared to civil courts, criminal courts are generally not as well-equipped to assess civil liability.

Victims of International Financial Crime and International Best Practices

The complexity of international financial crimes makes it difficult to identify all affected victims, and the varying legal frameworks across jurisdictions further complicate the process of ensuring adequate victim compensation. The lack of a standardized approach to victim eligibility and compensation means that many victims remain unrecognized and uncompensated, highlighting a significant flaw in the current system.

While there is no universally accepted approach to balancing efficiency and victim compensation in non-trial resolutions, international standards provide some guidance. For example, the United Nations Convention Against Corruption Coalition has proposed that States should consider “setting up dedicated funds and mechanisms to provide timely compensation to victims of corruption.”

Efforts have been made to address the situation by implementing domestic law that abides by international standards. The UK’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) has established general principles aimed at ensuring that international victims of white-collar crime benefit from asset recovery proceedings and compensation orders made in England and Wales. These principles encourage cooperation between different government departments to identify overseas victims, gather evidence, and support compensation claims, ensuring a transparent, accountable, and fair process. However, compensation orders are generally intended for clear and simple cases, and complex financial crimes often require more developed principles to provide adequate redress.

Conclusion: Towards a Balanced Approach

In navigating the complexities of non-trial resolutions in financial crimes, it is crucial to strike a balance between efficiently resolving cases and ensuring victims’ rights are upheld. While the importance of victim compensation is generally recognized across jurisdictions, the extent of their involvement varies. The role of victims must be carefully balanced to avoid disproportionate influence that could impede resolutions, lead to excessive claims, or violate the defendant’s rights. Key considerations include the carryover effect between criminal and civil proceedings, victims’ access to criminal evidence in pursuing a civil claim, mechanisms for joint victim compensation claims, the allocation of recovered assets among governments and victims, and more comprehensive principles to compensate international victims of complex financial crimes. Ultimately, the goal should be to develop non-trial resolution mechanisms that are both expedient and fair, ensuring that the role of victims is not forgotten and they are not left uncompensated in the pursuit of swift justice.

Stéphane Bonifassi is a Partner at Bonifassi Avocats, Lincoln Caylor is a Partner at Bennett Jones, Grégoire Mangeat is a Founding Partner at MANGEAT, Léon Moubayed is a Partner at Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg LLP, Jonathan Sack is a Partner at Morvillo Abramowitz Grand Iason & Anello PC, Andrew Stafford K.C. is Lawyer at Kobre & Kim LLP, Wolfgang Spoerr is a Partner at Hengeler Mueller, and Thomas Weibel is a Partner at VISCHER. The authors are Fellows at the International Academy of Financial Crime Litigators. This article is a summary of their working paper.

The views, opinions and positions expressed within all posts are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement (PCCE) or of the New York University School of Law. PCCE makes no representations as to the accuracy, completeness and validity or any statements made on this site and will not be liable any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author(s) and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author(s).