by Mehdi Ansari, Nader A. Mousavi, Juan Rodriguez, John L. Savva, Mark Schenkel, Presley L. Warner, Suzanne J. Marton, and Claire Seo-Young Song

Top left to right: Mehdi Ansari, Nader A. Mousavi, Juan Rodriguez, and John L. Savva.

Bottom left to right: Mark Schenkel, Presley L. Warner, Suzanne J. Marton, and Claire Seo-Young Song. (Photos courtesy Sullivan & Cromwell LLP)

On February 2, 2024, the Committee of Permanent Representatives to the European Union (“COREPER”) approved the final text of a proposed Regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending certain other EU laws (“AI Act”).[1] The AI Act is expected to be passed into law in Q2 2024, once adopted by the European Parliament and EU Council of Ministers.

The AI Act will establish a comprehensive code of rules affecting the entire value chain for artificial intelligence systems (“AI systems”) in the EU, including their design, development, importation, marketing and use, as well as the use of their output, in the EU. It will be the most sweeping regulation of AI systems in the world to date. Its key features are as follows:

- Scope: The AI Act will apply to all types of AI in all sectors (so-called “horizontal scope”), with a small number of exemptions for AI systems and their output used exclusively for military and scientific research and development purposes. Natural persons using AI systems for purely non-professional purposes will also be exempt.

- Regulatory obligations depend on AI system risk category: The AI Act will adopt a risk-based approach to regulating AI systems. It will impose varying degrees of regulation depending on the level of risk posed by the AI system.

- The highest risk category is “unacceptable risk.” AI systems in this category will be prohibited from sale or deployment in the EU.

- The next category, “high risk,” is broadly defined. AI systems in this category will be subject to stringent obligations, such as undergoing a conformity assessment.

- Moving down the risk spectrum, AI systems in the “specific transparency risk” category will be subject to transparency requirements. For example, providers of AI systems intended to directly interact with natural persons must ensure that the natural persons exposed to the AI systems are informed that they are interacting with an AI system.

- In addition to the above, the AI Act will establish rules in relation to general purpose AI models and a stricter regime for general purpose AI models with systemic risk.

- All other AI systems (which are considered to be “low or minimal risk”) will not be subject to additional regulatory obligations under the AI Act.

- Safeguards on the use of real-time remote biometric systems in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement: The use of ‘real-time’ remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible spaces for the purpose of law enforcement will be prohibited, with exceptions set out for specific use cases, such as enforcement activities for specified crimes, targeted searches for victims of specific crimes and prevention of terrorist attacks.[2]

- New EU AI agency and national enforcement agencies: A new European AI Office (“AI Office”) is being established within the Commission and will be tasked with the implementation of EU legislation on AI. The AI Office will monitor compliance with, and enforce, the obligations on providers of general purpose AI models. In tandem, the AI Act will require EU Member States to designate or establish national authorities to carry out the primary enforcement of the AI Act. Furthermore, a new EU Artificial Intelligence Board (“AI Board”) will be established. The AI Board will comprise the designated representatives of the relevant EU Member State authorities, the Commission and the European Data Protection Supervisor. The AI Board will advise and assist the Commission and Member States by issuing recommendations and opinions relevant for standardisation and uniform implementation of the new rules. In addition, the Commission will establish a scientific panel of independent experts to support the enforcement activities under the AI Act. The scientific panel will be tasked, inter alia, with alerting the AI Office of possible systemic risks of general purpose AI models.

- Substantial fines for non‑compliance: Marketing or deploying prohibited AI systems will be punishable by administrative fines of up to €35 million or 7% of total worldwide annual turnover, whichever is higher. Non-compliance with other provisions of the AI Act and the supply of incorrect or misleading information to relevant bodies and national authorities will be subject to fines with lower maxima. In deciding the amount of the fine, relevant factors, e., the nature, gravity and duration of the infringement and of its consequences and the size, the annual turnover and market share of the infringer will be taken into account.[3]

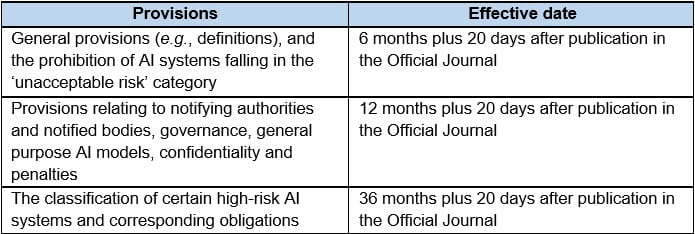

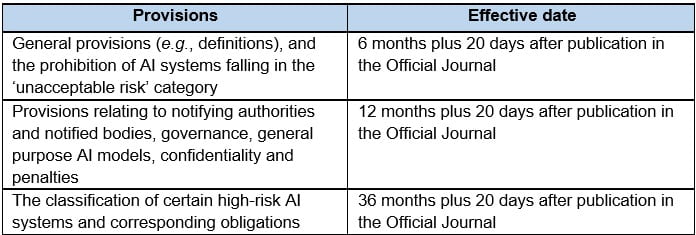

- Timing: The AI Act will come into effect 24 months plus 20 days after its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union (the “Official Journal”), subject to the following derogations for specific provisions:

BACKGROUND

In April 2021, the European Commission (the “Commission”) proposed a draft of the AI Act.[4] The aim was to deliver on the political commitment by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen to create “a coordinated EU approach on the human and ethical implications of AI.”[5] The AI Act is being enacted through the EU’s “ordinary” legislative procedure, which requires agreement among the Commission, the EU Council of Ministers and the European Parliament. On December 8, 2023, the European Parliament and Council reached a political agreement on the terms of the AI Act. On February 2, 2024, COREPER approved the final text of the AI Act. The AI Act is expected to be passed into law in Q2 2024, once adopted by the European Parliament and EU Council of Ministers.

A. KEY FEATURES OF THE AI ACT

The AI Act aims to ensure that the marketing and use of AI systems and their output, in the EU, comply with fundamental rights under EU law such as privacy, democracy, the rule of law and environmental sustainability, while encouraging the development of AI. The AI Act seeks to achieve these objectives by: (i) prohibiting outright certain AI systems considered to pose an unacceptable risk; and (ii) imposing various regulatory obligations with respect to other AI systems and their output.[6]

1. Scope

The AI Act defines “artificial intelligence system” as:

a machine-based system designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments.[7]

The AI Act will apply to all types of AI systems in all sectors, except AI systems and their output used exclusively for military and scientific research and development purposes. Natural persons using AI systems for purely non-professional purposes will also be exempt. The AI Act will apply to public and private entities, and operators of the relevant AI systems. An “operator” for these purposes means the provider of an AI system, a product manufacturer that markets or deploys a relevant AI system together with its own product under its own name or trademark, the deployer of an AI system, an authorised representative (i.e., a person that has accepted a written mandate from a provider of an AI system to carry out the obligations under the AI Act on its behalf), the importer of the AI system into the EU and the distributor of the AI system.

2. Risk-based classification and varying regulatory intensity

The central feature of the AI Act is its risk-based classification system, which applies different levels of regulatory obligation depending on the level of risk inherent in the particular AI system. AI systems with minimal risk will be subject to lighter rules (codes of conduct), while high-risk AI systems will have to comply with strict rules to gain entry into the EU market. The risk categories are as follows:[8]

a. Unacceptable risk AI systems: AI systems posing an unacceptable risk will be prohibited.[9] It therefore will be unlawful to market or deploy these systems in the EU. These systems are those that facilitate (i) the use of subliminal, manipulative or deceptive techniques with the objective to, or effect of, materially distorting people’s behaviour; (ii) exploitation of vulnerabilities with the objective to or effect of materially distorting people’s behaviour; (iii) social scoring for public and private purposes; (iv) real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces by law enforcement authorities (subject to narrow exceptions); (v) biometric categorisation of natural persons based on biometric data (subject to narrow exceptions for identifying crime victims and preventing crime); (vi) individual predictive policing; (vii) emotion recognition in the workplace and educational institutions (subject to narrow exceptions for medical and safety purposes); and (viii) untargeted scraping of the internet or CCTV for the purposes of creating or expanding facial recognition databases.

b. High-risk AI systems: AI systems that, while not posing an unacceptable risk, potentially have an adverse impact on individuals’ safety and fundamental rights are categorised as high risk and will be subject to rigorous legal obligations (summarised below).[10] Annex III to the final text of the AI Act lists the eight use cases of high-risk AI systems: (i) biometrics, insofar as their use is permitted; (ii) safety components of critical infrastructure, such as water, gas and electricity; (iii) educational and vocational training; (iv) employment, workers management and access to self-employment; (v) access to, and enjoyment of, essential private services (such as banking and insurance) and essential public services (such as healthcare and social security); (vi) law enforcement, insofar as their use is permitted by the AI Act; (vii) migration, asylum and border control management, insofar as their use is permitted by the AI Act; and (viii) administration of justice and democratic (e., voting) processes.[11] The Commission will be empowered to add, modify or remove use cases from Annex III and will be expected to keep this list up-to-date to ensure that it is future-proof.[12] From a practical perspective, being in the “high‑risk” category will have considerable significance because it comprises the AI systems that, while permitted in the EU, will be subject to the most stringent and burdensome obligations under the AI Act.

c. Specific-transparency-risk AI systems: AI systems that carry risks of manipulation of natural persons (such as chatbots) will be subject to specific transparency requirements. AI systems deemed to have specific transparency risks are those intended to directly interact with natural persons, such as emotional recognition systems, biometric categorisation systems and generative AI models. AI systems in the “specific transparency risk” category will be subject to transparency requirements. By way of example: (i) providers of AI systems intended to directly interact with natural persons should ensure that the natural persons exposed to the AI systems are informed that they are interacting with an AI system; (ii) deployers of emotion recognition systems or biometric categorisation systems (to the extent not prohibited under the AI Act) must inform natural persons of the operation of the system and process personal data in accordance with applicable EU law; (iii) deployers of deep fake-generating systems must disclose that the content has been artificially generated; and (iv) deployers of generative AI systems whose text is published without human review or editorial control for the purpose of informing the public on matters of public interest must disclose that such text has been artificially generated.[13] The required information must be conveyed in a clear and distinguishable manner to the natural persons at the time of their first interaction or exposure. The AI Office will draw up codes of practice regarding the detection and labelling of artificially generated or manipulated content, which the Commission will be empowered to adopt into EU law through implementing acts.[14]

d. Low or minimal risk AI systems: AI systems categorised as low or minimal risk can be developed and deployed in the EU without additional legal obligations. The vast majority of AI systems will fall into this category. Within 18 months of the AI Act’s entry into force, the Commission will provide a comprehensive list of practical examples of high-risk and non-high-risk use cases of AI systems.[15] The AI Office and Member States will facilitate the drawing up of a voluntary codes of conduct, which will provide guidance in respect of low or minimal risk AI systems and specific-transparency-risk AI systems.

3. Regulatory obligations in relation to high-risk AI systems

High-risk AI systems marketed or deployed in the EU will be subject to seven obligations under the AI Act:

a. Establishment of risk management systems: A risk management system must be established, implemented, documented and maintained in relation to high-risk AI systems, throughout the entire lifecycle of the AI system.[16] The risk management system must be regularly reviewed and updated, and comprise, to the extent that such risks can reasonably be mitigated or eliminated through the development or design of the AI system: (i) the identification and analysis of the known and reasonably foreseeable risks; (ii) estimation and evaluation of the risks that may emerge under conditions of reasonably foreseeable misuse; (iii) evaluation of other possibly arising risks based on the analysis of data gathered from the post-market monitoring system; and (iv) adoption of appropriate and targeted risk management.

b. Use of data for training, validating and testing AI models: The use of data for training, validating and testing of AI models will be subject to data governance measures.[17] These measures concern transparency as to: (i) the relevant design choices; (ii) the original purpose of data collection and data collection processes; (iii) data preparation processing operations; (iv) formulation of assumptions with respect to the information that the relevant data represents; (v) an assessment of the availability, quantity and suitability of the data sets that are needed; (vi) measures to detect, prevent and mitigate possible biases, in particular those likely to affect the health and safety of persons or EU fundamental rights; and (vii) identification of relevant data gaps or shortcomings that prevent compliance. See also Section B (Assessment) below.

c. Technical documentation: Technical documentation must be drawn up prior to a high-risk AI system being placed on the market, and must be kept up to date.[18] The technical documentation must demonstrate that the high-risk AI system complies with all applicable requirements and provide national authorities and conformity assessment bodies designated by each Member State with the necessary information to assess its compliance with those requirements.[19]

d. Record-keeping: High-risk AI systems must be designed and developed with capabilities enabling the automatic recording of events during their operation, in a way that conforms to the state of the art and recognised standards or common specifications.[20] At a minimum, records should provide information regarding the period of use, the reference database against which the input data has been checked by the system, the input data for which the search has led to a match and the identification of the natural persons involved in the verification of the results (as required by the standard of human oversight mentioned in (f) below).

e. Transparency obligations: High-risk AI systems must be designed and developed in such a way as to ensure that their operations are sufficiently transparent to enable deployers to interpret the system’s output and use it appropriately.[21] Providers of high-risk AI systems must provide instructions for use, which include the identity and contact details of the provider, characteristics, capabilities and limitations of performance of the AI system and any necessary maintenance and care measures to ensure the proper functioning of the AI system. See also Section B (Assessment) below.

f. Standards of human oversight: High-risk AI systems must be overseen by natural persons who have a sufficient level of AI literacy and the necessary support and authority.[22] The standard of human oversight must be proportionate to the risks associated with the AI system. Human oversight may involve abilities such as being able to monitor the AI system’s operation to detect anomalies and intervene or interrupt the system to safely stop the system.

g. Requirements of accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity: High-risk AI systems must be designed and developed in such a way that they achieve an appropriate level of accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity.[23] Consistent performance will also be assessed. Measures must be put in place to prevent or respond to possible errors, faults or inconsistencies, as well as attacks by unauthorised third parties.

4. Obligations of providers, importers, distributors and deployers of high-risk AI systems:

The AI Act will establish obligations on various actors along the AI value chain. Providers of high-risk AI systems must ensure that their AI systems comply with the seven requirements set out above and take corrective action immediately upon consideration that their high-risk AI system no longer complies with the AI Act.[24] They must also put in place a quality management system that ensures compliance with the AI Act and establish a post-market monitoring system that actively documents and analyses data to evaluate the system’s continued compliance with the AI Act. Importers of high-risk AI systems must ensure that the provider of the high-risk AI system has carried out the relevant conformity assessment procedure, drawn up the required technical documentation and, where applicable, appointed an authorised representative. Where the importer cannot ensure an AI system’s compliance with the AI Act, it must not place that system on the EU market. Distributors of high-risk AI systems must verify that the providers and importers of the high-risk AI system have complied with their obligations. Where a distributor has reason to consider that an AI system does not comply with the requirements, it must inform the provider and the national competent authorities immediately and not place the AI system on the market.

Stakeholders should remember that any distributors, importers, deployers and other third parties will be considered providers of high-risk AI systems and be subject to the relevant obligations if they put their name or trademark on an existing high-risk AI system, substantially modify an existing high-risk AI system or modify the intended purpose of an AI system such that the AI system becomes a high-risk AI system.[25] In these circumstances, the first provider will no longer be considered a provider for the purposes of the AI Act. Nevertheless, the former provider must closely cooperate and make available information that is required for the new provider to fulfil its obligations under the AI Act, unless the former provider has expressly excluded the change of its system into a high-risk system.

5. General purpose AI models

The AI Act defines a “general purpose AI model” as:

an AI model, including when trained with a large amount of data using self-supervision at scale, that displays significant generality and is capable to competently perform a wide range of distinct tasks regardless of the way the model is placed on the market and that can be integrated into a variety of downstream systems of applications. This does not cover AI models that are used before release on the market for research, development and prototyping activities.[26]

Providers of general purpose AI models must (i) draw up and keep up-to-date the relevant technical documentation of the model for the AI Office and the national competent authorities; (ii) draw up, keep up-to-date and make available information and documentation to providers who intend to integrate the model into their AI system; (iii) put in place a policy to ensure compliance with EU copyright law; and (iv) provide a publicly available and sufficiently detailed summary of the content used to train the model. Providers of general purpose AI models under a free and open-source license will only be required to comply with EU copyright law and provide a summary about the model’s training data, unless they are providers of AI models with systemic risks.

Providers of general purpose AI models with systemic risks will be subject to additional requirements, such as obligations to: (i) perform model evaluation, including adversarial testing; (ii) assess and mitigate possible systemic risks at EU level, including their sources; (iii) keep track of, document and report to the AI Office and national competent authorities relevant information about serious incidents and possible corrective measures; and (iv) ensure adequate cybersecurity protection for the model and its physical infrastructure.[27]

The European Standardisation Organisations will publish a harmonised standard for general purpose AI models.[28] Compliance with the harmonised standard will grant providers of general purpose AI models the presumption of conformity with the requirements, which can otherwise be demonstrated and approved separately by the Commission. In the interim, providers of general purpose AI models may rely on the codes of practice that will be drawn up by the AI Office.[29]

6. A New EU AI Agency and National Enforcement Agencies

An AI Office is being set up within the Commission to enforce the new rules for general purpose AI models, including setting the codes of practice, monitoring compliance and classifying AI models with systemic risks. The Commission will have the exclusive power to enforce and supervise obligations on providers of general purpose AI models. Such powers include the ability to request documentation, conduct model evaluations, investigate and request corrective measures (e.g., to restrict placement on the market, or withdraw or recall the general purpose AI model).[30] Furthermore, each Member State will nominate a representative to the AI Board, which will be an advisory body to the Commission and the relevant Member State authorities. The AI Board will advise on the implementation of the AI Act, and issue recommendations and opinions on the implementation and application of the AI Act. The Commission will also appoint stakeholders to an advisory forum to represent commercial and non-commercial interests, and provide industry and technical expertise to the AI Board and the Commission. In addition, the Commission will establish a scientific panel of independent experts to support the enforcement activities under the AI Act. The scientific panel will be tasked, inter alia, with alerting the AI Office of possible systemic risks of general purpose AI models.[31]

In addition, the Commission has emphasised the importance of national authorities in monitoring the application of the AI Act and undertaking market surveillance activities. Each Member State must establish or designate at least one notifying authority (i.e., the national authority responsible for setting up and carrying out the necessary procedures for the assessment, designation and notification of conformity assessment bodies and for their monitoring) and one market surveillance authority empowered to act independently to ensure the application and implementation of the AI Act. The AI Act will allow natural and/or legal persons to lodge complaints with the market surveillance authorities of individual Member States concerning non-compliance.

7. Penalties

The AI Act will provide for harsh penalties for infringement of the prohibition rules or non-compliance with its data requirements — up to €35 million or 7% of total worldwide annual turnover, whichever is higher. For non-compliance with any of the AI Act’s other requirements, the fines can be up to €15 million or 3% of worldwide annual turnover, and €7.5 million or 1% of worldwide annual turnover for the supply of incorrect, misleading or incomplete information to the relevant national authorities. Fines for providers of general purpose AI models will be imposed by the Commission. All other fines will be imposed by the relevant authority empowered to do so under Member State national law.

8. Timing

The AI Act will come into effect 24 months plus 20 days after its publication in the Official Journal, subject to the following derogations for specific provisions:

In addition, codes of practices will be published at the latest nine months after entry into force.[32]

B. ASSESSMENT

Although significant stakeholders, including President Macron, have expressed concerns that the AI Act will stifle innovation in the EU, the AI Act aims to remain innovation friendly. AI regulatory sandboxes and testing in real-world conditions will be allowed, subject to specifically agreed conditions and safeguards being put in place.[33] In addition, small and medium enterprises will benefit from some exemptions that apply in limited circumstances under the AI Act. It remains to be seen whether such exemptions will sufficiently ease the burden on small and medium enterprises.

There are a number of foreseeable challenges for operators of AI systems. While the AI Act will apply a graduated approach in respect of the different risk levels of AI systems, there may be a period of uncertainty while enforcement agencies and businesses determine the risk levels of AI systems. It also remains to be seen how burdensome and time consuming the requirement for prior assessments will be for stakeholders, in an industry where change happens extremely rapidly. The obligations imposed on providers of high-risk AI systems, such as the data governance requirements relating to training data (see Section A(3)(b) above) and transparency obligations to ensure the appropriate use and interpretation of the output of high-risk AI systems (see Section A(3)(e)), pose technical and industry-wide challenges. Compliance with the numerous obligations in respect of high-risk AI systems, specific-transparency-risk AI systems and general purpose AI models will require operators of such AI systems to establish and implement new internal measures that may be time consuming and costly. In addition, harmonisation in practice may take longer, as many Member States do not have AI regulations or experience in monitoring AI systems.

Although the AI Act determines whether, and if so, under what conditions, AI systems can be marketed or deployed in the EU, it is intentionally silent on the question of liability for harm caused by AI systems or their output. While that will be a question of national law, rather than being harmonised under EU law, the EU institutions have nevertheless recognised that it merits some treatment under EU law. Accordingly, on September 9, 2022, the Commission proposed the Directive on adapting non-contractual civil liability rules to artificial intelligence (AI Liability Directive).[34] The AI Liability Directive is currently awaiting the report of the Committee on Legal Affairs.[35] The key features of this Directive are that it will (i) create a fault-based liability regime and provide an effective basis for claiming compensation for intentionally or negligently caused damage; (ii) allow the court to order disclosure of evidence from providers of high-risk AI systems; (iii) create a rebuttable presumption of a breach of duty of care where the defendant fails to comply with a court’s order for disclosure of evidence; and (iv) create a rebuttable presumption of causation between the defendant and the AI system’s act or omission where the defendant breached its duty of care.

The AI Act will have no impact on intellectual property law affecting AI and its use. Therefore, fundamental questions such as whether an AI system can be named as the inventor in patent applications, and the rules determining who owns copyright and other rights in works generated by AI systems, will continue to be regulated under Member State national law and the relevant international treaties.

Footnotes

[1] This memo (including the relevant citations below) is based on the version of the AI Act put before COREPER, which has been made public. The AI Act remains subject to further refinement, but not as to substance. The definitive version of the AI Act will be published in the Official Journal of the European Union once adopted.

[2] Article 5(1)(d) of the AI Act.

[3] Article 71 of the AI Act.

[4] European Commission, Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Laying Down Harmonised Rules On Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) And Amending Certain Union Legislative Acts, 21 April 2021, COM(2021) 206.

[5] Ibid., paragraph 1.1.

[6] The full press release is available here: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/12/09/artificial-intelligence-act-council-and-parliament-strike-a-deal-on-the-first-worldwide-rules-for-ai/.

[7] Article 3(1) of the AI Act.

[8] As answered in the Commission’s published Q&A on 12 December 2023: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_21_1683.

[9] Article 5 of the AI Act.

[10] As defined in the European Charter of Fundamental Rights.

[11] As answered in the Commission’s published Q&A on 12 December 2023: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/QANDA_21_1683.

[12] Article 7 of the AI Act.

[13] Article 52 of the AI Act.

[14] Article 52(4a) of the AI Act.

[15] Article 6(2c) of the AI Act.

[16] Article 9 of the AI Act.

[17] Article 10 of the AI Act.

[18] Article 11 of the AI Act.

[19] Notified bodies will be assigned an identification number and the list of all notified bodies will be publicly available and kept up-to-date by the Commission, Article 35 of the AI Act.

[20] Article 12 of the AI Act.

[21] Article 13 of the AI Act.

[22] Article 14 of the AI Act.

[23] Article 15 of the AI Act.

[24] Article 21 of the AI Act.

[25] Article 28 of the AI Act.

[26] Article 3(44b) of the AI Act.

[27] A general purpose AI model will be deemed to carry systemic risk if it has high impact capabilities (evaluated on the basis of appropriate indicators and benchmarks) or the Commission decides, ex officio or following a qualified alert by the scientific panel, that the general purpose AI model has equivalent capabilities or impact. AI systems with a total computing power of more than 10^25 floating point operations per second (FLOPs) will be presumed to carry systemic risks, Article 52a of the AI Act.

[28] Article 40(2) of the AI Act.

[29] Article 52c(3) of the AI Act.

[30] Article 68f and Articles 68i-68k of the AI Act.

[31] Article 58b of the AI Act.

[32] Article 85(3) of the AI Act.

[33] A controlled environment to develop, test and validate AI systems.

[34] European Commission, Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on adapting non-contractual civil liability rules to artificial intelligence (AI Liability Directive), 28 September 2022, COM(2022) 496.

[35] Procedure file for the AI Liability Directive is available here: https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/popups/ficheprocedure.do?lang=en&reference=2022%2F0303(OLP).

Mehdi Ansari, Nader A. Mousavi, Juan Rodriguez, John L. Savva, Mark Schenkel, and Presley L. Warner are Partners, Suzanne J. Marton is an Associate, and Claire Seo-Young Song is a Trainee Solicitor at Sullivan and Cromwell LLP. The post first appeared on the firm’s “Regulation of Artificial Intelligence” blog.

The views, opinions and positions expressed within all posts are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement (PCCE) or of the New York University School of Law. PCCE makes no representations as to the accuracy, completeness and validity or any statements made on this site and will not be liable any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author(s) and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author(s).