How MIT’s data-sharing consortium known as Integrity Distributed can help companies meet the DOJ’s recently updated corporate enforcement guidelines, while also identifying potentially improper payments.

by Vincent M. Walden and Eduardo Lemos

From left to right: Vincent M. Walden and Eduardo Lemos. (photos courtesy of the authors)

A new data-sharing consortium led by a nonprofit at MIT is allowing the collaboration between companies to improve their improper payments detection capabilities by up to 25% than when each company’s model is performed in isolation. By increasing their fraud detection capabilities, companies will be in a better position to align with the DOJ updated expectations for corporations to achieve the identification of misconduct and to voluntarily self-disclose.

Introduction

On January 17, 2023, Assistant Attorney General (AAG) Kenneth A. Polite, Jr. delivered remarks on revisions to DOJ Criminal Division’s Corporate Enforcement Policy and simultaneously released the revised policy.

The DOJ’s updated policy anticipates that when a company has uncovered criminal misconduct in its operations, the clearest path to avoiding a guilty plea or an indictment, and to perhaps achieving a declination, is voluntary self-disclosure.

Another key factor that will be assessed by prosecutors when they decide what to do in relation to any particular corporate misconduct is the fact that, at the time of the misconduct and the disclosure, the company had an effective compliance program and system of internal accounting controls that enabled the identification of the misconduct and led to the company’s voluntary self-disclosure.

The message by AAG Kenneth A. Polite could not have been clearer: “Make no mistake – failing to self-report, failing to fully cooperate, failing to remediate, can lead to dire consequences.” The announcement produced shockwaves in the compliance industry, especially for the increased focus and incentives for voluntary self-disclosure from corporate actors.

However, the decision to voluntarily self-disclose is only possible when the company detects the misconduct in the first place, so a parallel consequence of the revised DOJ’s Policies is the need for an uptick in the effective detection of corporate misbehavior. As pointed out by the AAG, “a functioning compliance program with effective detection mechanisms best positions companies to not only identify misconduct in the first instance, but to make the important decision of whether to disclose it.“

Detecting corporate crime such as fraud and corruption is challenging, but possibly using advanced analytics and machine learning technologies on top of legal and subject matter expertise can improve a company’s detection capabilities. And, when organizations work together in collaboration, it’s now proven the results are even better. Here we look at how a consortium led by a nonprofit at MIT is helping organizations share data without compromising privacy in their fight against fraud.

Challenges that Deter Corporate Efforts to Detect Fraud and Corruption.

Companies work hard to detect and prevent fraud and corruption. Still, it can be challenging for businesses to identify behaviors that cross the line — particularly where employees are determined to commit a crime and then take steps to conceal their behavior. As anti-fraud professionals, we’re increasingly using data analytics to identify and monitor these risks for our organizations or clients. A critical factor when evaluating compliance programs involves determining if compliance and control personnel have sufficient access to relevant data sources. Can they access information to implement timely monitoring, policy testing and controls evaluation? As the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) indicates, this is even more critical in a regulatory environment that increasingly requires monitoring amid the ever-expanding availability of new data sources. This is true not just during due diligence, but “throughout the lifespan of the third-party relationship,” says the DOJ.[1]

Corruption often tends to flourish where multiple actors compete in opaque markets in a race to the bottom, often leaving victims unaware of wrongdoing occurring across multiple organizations. Against that backdrop, we shouldn’t attack corruption alone in organizational silos, but rather encourage transparency across organizations and industry sectors, sharing insights, risk profiles and third-party attributes that describe a potentially improper or corrupt payment.

Even so, this approach raises numerous challenges. First, detecting signs of fraud from “noise” across uneven and sometimes unreliable data sets is tough. Even the most sophisticated organizations tend to only have access to reliable data related to their own vendors and customers, which is just a fraction of the global marketplace. Second, it can be difficult to create a transparent anti-fraud framework while also preserving the required privacy necessary for organizations to maintain their competitive edge. It makes little sense to trade a corruption problem for a competition or privacy one. A third challenge is to create a collaborative framework that’s cost effective. Technologies tend to flourish only when their new users don’t have to risk significant resources on a “bet” that it will work. Last, contributing members in any collaborative effort need to trust each other. It’s important that participants are confident that each member is acting in good faith in terms of how they are applying insights and translating such results into action.

About InDi

InDi is a nonprofit initiative that allows organizations all over the world to contribute their anti-fraud and anticorruption intelligence in a secure, anonymous information-sharing consortium model. The platform allows organizations to train algorithms that detect patterns of fraud and corruption in their respective industries. Those algorithms (but not the underlying data) are contributed to the consortium, enhancing the collective intelligence of the “super-algorithm” in a secure platform. The process is iterative and collaborative, feeding data-hungry algorithms for optimal performance. As more data and algorithms are contributed, artificial intelligence learns and improves at a rate much faster than would be possible at any single company. Through this unique model of collaboration and data analytics, all of the participating organizations benefit, and the learning is continual throughout the integrity distributed network.[2]

About the research

In a limited research study funded by the AB InBev Foundation, InDi brought together forensic accounting technology and data science professionals from Kona AI, MIT, and Harvard Business School, working in cooperation with Fortune 500 companies and leading AmLaw 100 law firms that focus on white-collar crime and anti-corruption, to design, develop, implement and test the new platform.

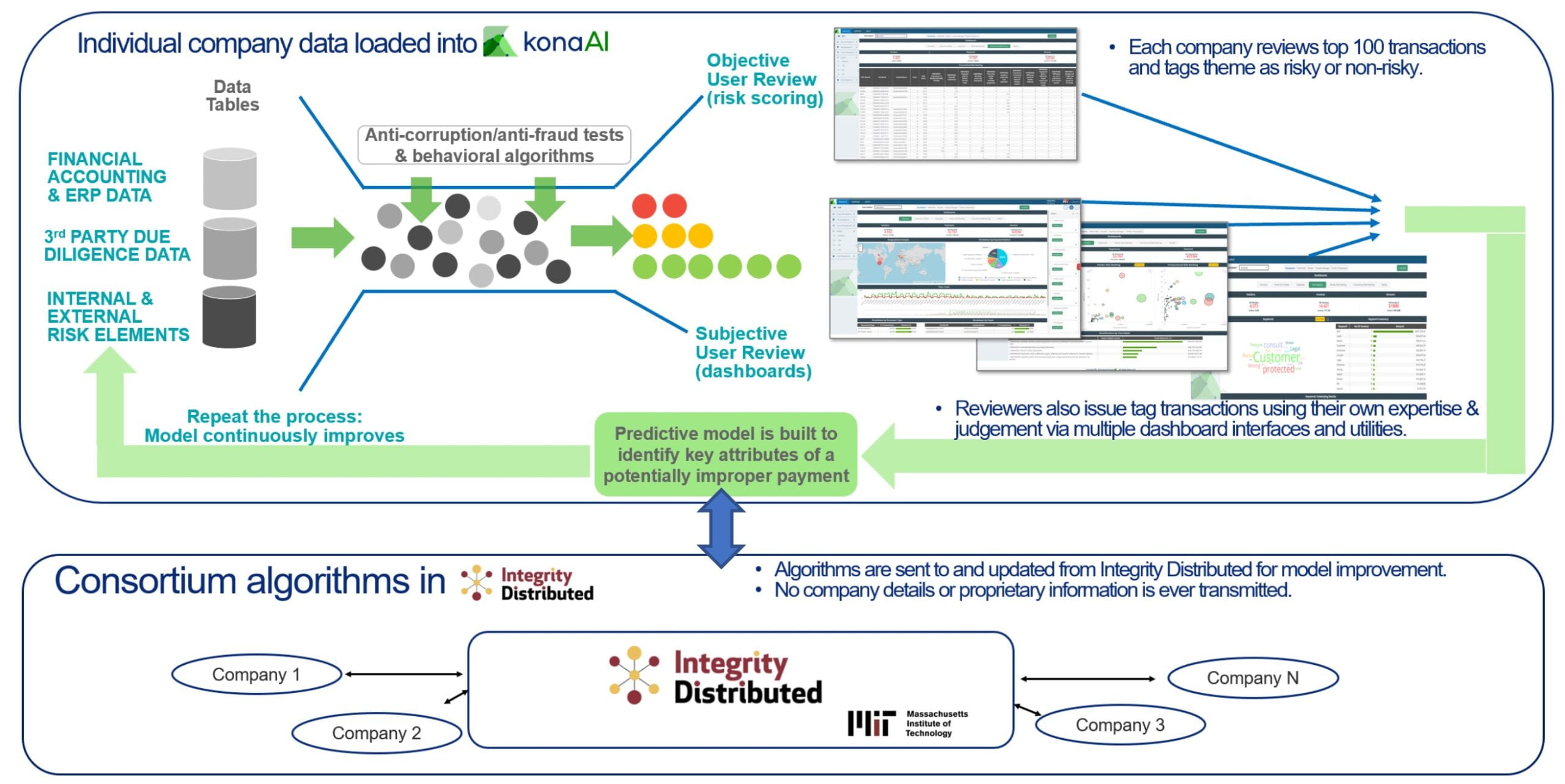

Several companies extracted relevant third-party payments data from their enterprise resource planning systems (such as SAP or Oracle procure-to-pay systems) and loaded the information into a consistent unified data model (or UDM) developed by Kona AI. On a company-by-company basis, payment risks were risk-scored, first by the model and across an extensive library of tests and behavioral algorithms, and each company’s representative and/or its outside counsel reviewed the highest-risk transactions. Using an approach that originated in e-discovery known as technology assisted review, the team created a predictive model for each company designed to proactively identify a potentially improper payment based on the attributes of each transaction.[3] Finally, the team combined each company’s model into one “super-model,” using a neural-network statistical model to retain and share insights while protecting data privacy and anonymity.

“This research was the first-of-its kind in terms of companies working together to fight global corruption using advanced analytics,” says Francis Hounnongandji, CFA, CFE, President & CEO of the Institut Français de Prévention de la Fraude, based in Paris, France. “The concept around data-sharing consortiums to fight financial crimes or cyber risks is certainly not new. Seeing companies work together and driving results in this initial cohort, without having to share underlying data, looks promising for compliance programs in the future.”

With this initial cohort of companies, the results of the super-model indicate that the predictive value of identifying a potentially improper payment is 25% greater when companies collaborate compared to results when each company’s model is performed in isolation. As more companies are added to the cohort in 2023, research team expects the super-model results will continue to improve.

Building predictive models to fight global corruption

The InDi consortium is building upon recent advances in the decentralized machine learning and privacy-enhancing technologies to develop what MIT calls split learning. This is a technique that allows participating entities to train machine learning models without sharing any raw data.[4] InDi participants integrated split learning technology with the know-how of anti-corruption experts and workflows to form a distributed model to detect vendor fraud, corruption, and circumvention of controls.

Financial data from SAP or Oracle (or both) was exported from each company’s enterprise resource planning (ERP) system, a software system used to manage different operations in a firm such as accounting.[5] Specifically, procure-to-pay vendor payment information was the key data source. Additional third-party risk questionnaires, watchlists, or historical investigative results also supplemented and enriched the data. The data was then passed through an extensive library of over 100 anti-fraud, corruption and circumvention of controls tests and behavioral algorithms that participants provided. Thereafter, it was risk-scored (i.e., prioritized) based on those transactions meeting multiple risk criteria. Further, some companies were able to enhance their dataset with existing, known investigation findings such as high-risk transactions, vendors, general ledger accounts and other descriptive risk criteria to accelerate training of their predictive model. We found that those companies that tracked that information and could feed this information into their predictive model had noticeably better results based on standard performance metrics.

The Figure below illustrates how company-specific data was maintained and analyzed, with insights and algorithms being shared in a secure manner with InDi. This partnership between InDi and the participating companies is what forms the consortium — the Kona AI platform was simply the technology used to house the consortium concept and run the algorithms.

Source: KonaAI

Predictive model results

InDi hypothesized an improved predictive model performance using distributed machine learning algorithms, such as split learning, to better detect fraud, corruption, and circumvention of controls without sharing the underlying proprietary commercial data. In line with this hypothesis, the research team observed that the performance of the distributed prediction model’s precision and recall metric (known as an F1 score) increased 25% from 0.47 (individual) to 0.59 (distributed) upon simulating third-party payment data across 50 million records.

Please note that these results were preliminary as of November 2022. InDi plans to continue to add more companies to the consortium with a Phase 2 Cohort beginning the first quarter of 2023. Based on the preliminary results, the InDi team anticipates further model improvement and insights for the consortium participants.

What’s ahead for InDi?

Formed in June 2022, InDi is still in its infancy stage; however, it’s gaining a tremendous amount of interest and support from mid-to-large global organizations and governments. One of the key goals for the first quarter of 2023 is to increase the number of companies contributing to the consortium across a number of industries. As research and funding expands for the nonprofit, InDi may branch out and conduct additional research and model-building beyond third-party risk and into other areas for fraud and corruption.

To learn more about InDi and how your organization might be a candidate for participation, InDi invites anti-fraud professionals to visit their website at www.integritydistributed.com.

Footnotes

[1] See “Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs [Updated June 2020],” U.S. Department of Justice, Criminal Division, tinyurl.com/3ut6av2n.

[2] A short video clip provides more information on InDi and the participating law firms who helped advise on this initiative: vimeo.com/751882452.

[3] See Vincent Walden’s Innovation Update column “Using Technology-Assisted Review to Uncover Suspicious Transactions,” Fraud Magazine November/December 2022 FM issue, tinyurl.com/m8zm2mz3.)

[4] See “MIT Media Lab’s Split Learning: Distributed and collaborative learning,” tinyurl.com/3yjfhzfz.

[5] See “Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP): Meaning, Components, and Examples,” Investopedia, Sept. 10, 2022, tinyurl.com/4xkrn588.

Vincent M. Walden, CFE, CPA, is the CEO of Kona AI, an AI-driven anti-fraud and compliance technology company providing easy-to-use, cost-effective payment and transaction analytics software around corruption, investigations, fraud prevention and compliance monitoring. Contact Walden at vwalden@konaai.com. Eduardo Lemos is the Head of Legal at J Global Energy Holdings and a former Student Fellow of the Program of Corporate Compliance and Enforcement at NYU School of Law.

The views, opinions and positions expressed within all posts are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement (PCCE) or of the New York University School of Law. PCCE makes no representations as to the accuracy, completeness and validity or any statements made on this site and will not be liable any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright or this content belongs to the author(s) and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author(s).