Countries around the world are beginning to embrace negotiated corporate criminal settlements, cognizant of U.S. federal prosecutors’ success in using deferred and non-prosecution agreements (hereinafter D/NPAs) to impose both substantial monetary sanctions and mandated reforms. Negotiated settlements, and the mandates they impose, can materially enhance governments’ ability to deter corporate crime when used effectively (Arlen and Kahan 2017).

Yet the existing U.S. approach to mandates needs to be reformed because it suffers from a material weakness: the Department of Justice provides less guidance and formal oversight over mandates imposed through D/NPAs than is required to ensure that prosecutorial authority over mandates is consistent with the Rule of Law.

Under existing U.S. policy, prosecutors can, and usually do, use D/NPAs to require corporations to undertake specific internal governance reforms. Prosecutors imposing these reforms are not limited to duties established by regulators or legislatures. Nor are they restricted to a set of reforms set forth by senior officials in the criminal division. Instead, prosecutors entering into D/NPAs have discretion to impose new duties on corporations that they consider appropriate—duties to which the firm would not be required to comply absent the settlement. These duties can differ from those imposed on other firms entering into D/NPAs for similar conduct. Such mandates can include adopting a prosecutor-approved compliance program, altering management and the Board of Directors, implementing internal reporting programs, and prohibiting the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) from serving as Chairman. Mandates sometimes go as far as precluding firms from participating in specific business arrangements, and regularly require firms to accept and pay for an external monitor (Arlen and Kahan 2017).

These prosecutor-imposed mandates can be justified in the right circumstances (see blog post ”Corporate Governance Reform Through Deferred Prosecution”). Yet the DOJ’s existing policies give too much discretion to individual prosecutors’ offices to create and impose the mandates that they singularly deem appropriate. As I explain below, and in an article in the Journal of Legal Analysis, this approach fails to comport with the Rule of Law.

Rule of Law

The Rule of Law is a simple idea with fundamental implications: individuals must be governed by laws and not individual persons. Conformity requires that no individual government actor be granted the right to unilaterally create and impose new legal duties on others. Such broad discretion risks serving private aims or entrenching idiosyncratic views. In line with the Rule of Law, governments must limit individual discretion over duties imposed and promote consistency in duties imposed on similarly situated individuals.

The Rule of Law and Executive Discretion

Traditionally, the U.S. system of separation of powers helped ensure that no one individual, or office, asserted excessive authority over others. Authority to create, interpret, and enforce duties was divided across the three branches of government. Each served as a check on the other.

In modern societies, however, considerable power is concentrated in the executive branch to create new legal duties, enforce them, and adjudicate their breach. This discretionary authority to impose new legal duties can be consistent with the Rule of Law, but only if executive discretion is constrained to ensure that no individual person in the executive branch has unilateral authority to create, impose, and enforce new duties. Rule of Law concerns are enhanced when new duties can be imposed on specific individuals, instead of on categories of similarly situated people.

Modern states employ both ex ante and ex post constraints to bring executive branch discretion within the Rule of Law. First, they constrain the scope of authority granted to executive branch actors to create and impose new duties. In some cases, executive branch actors can only enforce duties created by parties outside the executive branch (e.g., legislatures). In others, executive branch actors have authority to create and enforce new duties, but the authority is allocated to different offices within the executive branch. Governments also limit individual discretion by requiring collective decision-making with respect to new duties, as occurs with formal rule-making by independent agencies. Public notice and comment, combined with the requirement that rules apply to categories of persons, indirectly limit discretion by providing a political counter-weight to idiosyncratic decisions.

In addition, modern societies promote conformity with the Rule of Law by requiring oversight and approval of decisions that alter people’s rights. This oversight can be provided by either a central authority within the executive branch or an external party, such as the judiciary. Oversight helps ensure that the decision is consistent with the public good and is not the product of idiosyncratic views or self-serving aims.

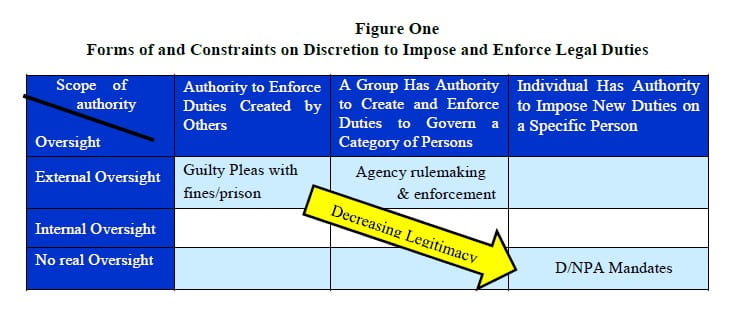

Figure One shows how ex ante limitations on the scope of executive authority and ex post oversight can interact in two traditional exercises of executive branch discretion to enable governments to grant discretion to agents within the executive branch while limiting the risk that the person with authority will use it to create, impose, and enforce duties idiosyncratically. Consider prosecutors’ decisions to enter into traditional guilty pleas with individuals imposing imprisonment or monetary sanctions. In exercising discretion, prosecutors enforce duties created by others, subject to oversight by judges with final authority over sanctions. Formal agency rule-making by independent agencies involves collective decision-making regarding new duties applicable to categories of people; the validity of the duties imposed and their enforcement is subject to oversight by the courts.

Why D/NPA Mandates Are Not Consistent with the Rule of Law

D/NPA mandates are not imposed through a process that includes protections through formal internal or external oversight. The Department of Justice has not provided federal prosecutors with clear guidelines governing either the decision to impose mandates or the form that mandates should take. Instead, federal prosecutors entering into D/NPAs can unilaterally decide both whether to require mandates and what mandates to impose in order to deter misconduct. In addition, the criminal division does not provide any formal oversight over most of the mandates imposed. Finally, U.S. Attorneys designing mandates are largely free from any external oversight over the mandates they impose. Judges play little, if any, supervisory role. NPAs are not filed in court. DPAs are filed in court, but currently judges do not have authority to assess the appropriateness of any mandates imposed.

The end result is that U.S. Attorneys’ Offices have authority to create new duties, individually, based on a prosecutor’s view of what reforms serve the public interest. Without any ex ante or ex post check by an independent decision-maker. This degree of discretion does not conform to the Rule of Law.

Consent Does Not Suffice

Of course, D/NPA mandates are imposed by consensual agreements. Private parties can enter into voluntary contracts without implicating Rule of Law concerns. The same cannot be said for federal prosecutors, however.

Prosecutors, unlike private parties, bargain on behalf of the state, invoking the threat of seeking to use the state’s police power should the bargain fail. Their authority to bargain comes from the public and thus must be used in the public interest. Commitment to the Rule of Law requires that prosecutors be constrained to use this state-given authority to impose settlement terms that genuinely serve the public interest. This requires greater ex ante constraints on and ex post oversight of the mandates they impose in order to both ensure mandates serve the public interest and are imposed consistently on similarly situated firms.

Conclusion

The Department of Justice is correct that some firms cannot be reformed unless mandates are imposed (Arlen and Kahan 2017). But the use of D/NPAs to impose mandates requires prosecutors to act as quasi-regulators, creating new duties to govern select firms. Congress long ago understood that regulators should not be free to intervene individually to unilaterally create new duties, outside the light of day. Commitment to the Rule of Law requires Congress or the Department of Justice to guide and constrain prosecutorial discretion in designing D/NPA mandates.

Reference

Jennifer Arlen and Marcel Kahan, Corporate Governance Regulation Through Non-Prosecution, 84 University of Chicago Law Review 323 (2017).

Jennifer Arlen is the Norma Z. Paige Professor of Law and Director of the Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement, New York University School of Law. This post is based on a longer article available here.

Disclaimer

The views, opinions and positions expressed within all posts are those of the author alone and do not represent those of the Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement or of New York University School of Law. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them.