In recent years, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has increased guidance to entities regarding government expectations as to what I refer to as “compliant behaviors” – maintenance of an effective pre-existing compliance program, post-enforcement adoption of an effective compliance program, cooperation with a government investigation, and self-disclosure of misconduct – and increased transparency in criminal cases as to the benefits defendants can expect to receive for engaging in those behaviors. In the health care industry, however, it is not criminal prosecution but the civil False Claims Act (FCA) which represents the government’s primary means of fraud enforcement. With no parallel increase in transparency with regard to FCA cases, the health care industry and the defense bar have expressed skepticism regarding the actual payoff they might realize by engaging in compliant behaviors, even as resources devoted to health care compliance have skyrocketed. DOJ’s response has been a series of public statements amounting to, “trust us, they matter,” and there has been no mechanism to test those assurances – until now.

In response to changes in the tax code, DOJ made adjustments in 2018 to its practice of disclosing information regarding FCA settlements – changes which have shaken loose data that provides an opportunity to test DOJ’s claims of rewarding compliant behaviors in civil cases. In a new article, forthcoming in the Utah Law Review, I examine this newly available data, which seemingly confirms some assumptions of the defense bar while also raising new and troubling issues.

Background

The False Claims Act Statute provides that a person who violates the FCA “is liable to the United States Government for a civil penalty [per claim], plus 3 times the amount of damages which the Government sustains because of the act of [the person violating the FCA].” This leaves a significant range between single damages (which make the government whole) and the maximum recovery available under the statute. And this multiplier range provides a clear opportunity for the government to motivate business organizations to engage in compliant behaviors. It is here where DOJ has asked the health care industry and the defense bar to trust that an impact exists and that engaging in compliant behaviors will reduce the multiplier a defendant is required to pay to resolve a potential FCA violation.

Until recently, multipliers were kept secret – DOJ needed only announce a settlement figure and leave everyone guessing as to how “tough” the settlement was. Even the settling company frequently did not know the multiplier DOJ used to resolve the case. That changed, however, with the 2017 passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

Section 13306 of the Act made clear that business organizations can deduct only those portions of settlements paid to the government that they can establish were paid as restitution or expended to come into compliance with the law and that the government has an obligation to provide notice to the Internal Revenue Service and to the settling party of the restitution amount contained within civil settlements. In response, DOJ has been including the “restitution” figure in FCA Civil Settlement Agreements (CSAs) since early 2018, from which the multiplier used in each particular case can be calculated.

Analysis of Newly Available Data

For the forthcoming article, I attempted to collect and review the CSAs from all civil-only FCA settlements entered into between health care business organizations and DOJ between early 2018 and May 31, 2019, as well as the accompanying DOJ press releases and other public statements made by DOJ or the settling defendants. Where possible, I tracked: the dollar amount of the resolution; the amount of the resolution which constituted restitution under the CSA; whether the case stemmed from the filing of a qui tam; the U.S. Attorney’s Office involved in the case; whether DOJ’s Commercial Litigation Branch was involved in the case; whether there were indicia of acceptance of responsibility; and whether there were indicia of compliant behaviors.

Examination of this data demonstrates that wide-ranging, structural changes are necessary. The data raises substantial questions about: the quantum of credit given for cooperation; conduct DOJ values in resolving FCA cases; and the degree of consistency in cases settled by U.S. Attorney’s Offices across the country. For example, analysis of the data reveals inconsistent benefits for cooperation. Cases where defendants self-disclosed misconduct or cooperated were often not treated more leniently than cases where defendants did not self-disclose or cooperate, and a review of more than 100 settlements did not find a single instance in which DOJ purported to give an entity a reduction based on its pre-existing compliance program. At the same time, DOJ appears to be greatly rewarding defendants for agreeing to settle – highlighting concerns both with regard to whether DOJ is achieving adequate deterrence and with regard to whether the FCA’s potential penalties are coercing settlements. And the data appears to show significant variation in settlement positions depending on the identity of enforcing DOJ component, with cases handled by DOJ’s Civil Division in Washington, D.C. treated more leniently than cases handled solely by U.S. Attorney’s Offices across the country.

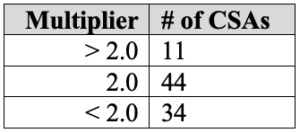

Despite DOJ’s statements regarding the potential for treble damages plus penalties under the False Claims Act, for the 89 CSAs for which the multiplier could be determined, the mean multiplier was 1.78 and the median multiplier was 2.0. Of those 89 CSAs, 78 (88%) were at or below double damages – 44 were at double damages and 34 were between 1.0-1.9, seemingly confirming widespread sentiment amongst industry and the defense bar that settlement multipliers are rarely above double damages.

There were only 11 CSAs with multipliers above 2.0, and neither the CSAs nor the DOJ press releases provided an explanation for why they had a higher than default multiplier. If those 11 organizations engaged in conduct DOJ wishes to disincentivize, the lack of transparency prevents any such general deterrence from taking place.

The data also revealed a statistically significant difference in the multiplier in cases handled by individual U.S. Attorney’s Offices without the involvement of the Commercial Litigation Branch in Washington as compared to those cases where the Commercial Litigation Branch was involved in the resolution. The mean multiplier for cases without the involvement of the Commercial Litigation Branch (1.86) was significantly higher than the mean multiplier for cases with the involvement of the Commercial Litigation Branch (1.66). While it is possible to speculate as to why U.S. Attorney’s Offices seem to be tougher on defendants than the Commercial Litigation Branch, arguably more important than the “why” is the simple fact of the disparity. Structurally, there is simply no DOJ guidance – neither public nor internal – to guide U.S. Attorney’s Offices in calculating FCA multipliers. DOJ officials have made statements trumpeting the potential exposure for defendants under the statute, but have provided no guidance to the field as to how they should determine numbers below the maximum.

After decades of DOJ providing no guidance at all as to the impact of corporate cooperation and self-disclosure on the resolution of FCA cases, DOJ finally provided guidance on May 7, 2019, with a statement and a memo focused on what conduct would constitute cooperation in the eyes of DOJ and strong statements that compliant behaviors would lead to reduced FCA multipliers. But the data calls into question whether DOJ is actually providing a benefit at all, even where DOJ acknowledges a company has engaged in compliant behaviors, including cooperation and even self-disclosure.

With criminal resolutions, fine calculations are governed by the United States Sentencing Guidelines and the impact of compliant behaviors on determining the fine amount is visible in plea and deferred prosecution agreements. Even more detail is given in agreements falling under DOJ’s recent FCPA Corporate Enforcement policy, aimed specifically at providing more transparency and certainty in the hopes of encouraging compliant behaviors. With the FCA, however, even with the change in the tax code making multipliers calculable from settlement agreements, and even since release of the memo claiming to provide guidance as to what behavior would be rewarded, DOJ has not been providing details as to how those multipliers were calculated. The health care industry and the defense bar are thus left to interpret the sparse information available in order to test the government’s promises.

From the information available, however, there is reason to be skeptical of DOJ’s claims of consistent rewards for compliant behaviors. My analysis identified several examples of defendants receiving above-mean 2.0 multipliers despite clear evidence of substantial cooperation, including references to the defendant’s cooperation in some of the CSAs and DOJ press releases. At the same time, several defendants received multipliers below 2.0 despite clear evidence that they did not even accept responsibility – never mind provide cooperation – regarding the alleged wrongdoing, and where there was no visible evidence of compliant behavior.

That is not necessarily to say the first group did not receive adequate credit for their cooperation – it is theoretically possible those multipliers would have been above 2.0 if not for their cooperation – or that there were not other reasons for the second group to receive below 2.0 multipliers. Given the lack of transparency, it is theoretically possible the multipliers in those cases do reflect consistent rewarding of compliant behaviors by DOJ. But if these resolutions do reflect a consistent rationale for determining multipliers in individual cases, including a true cooperation or acceptance of responsibility benefit, the lack of transparency necessarily means they fail to adequately inform industry and the defense bar of the existence and extent of those benefits.

Conclusion

No longer left in the dark about the impact of compliant behaviors in calculating FCA resolutions, the health care industry may be less likely to continue investing in compliance programs at the same rate, to cooperate with government investigations, and especially to self-disclose misconduct to the government. The analysis reveals that a detailed structure of DOJ’s calculations in FCA settlements, with calculations transparent in each FCA resolution, is needed to accomplish DOJ’s goal of encouraging cooperation and investment in compliance programs, as well as to provide an assurance that like cases are treated alike.

Jacob T. Elberg is an associate professor of law at Seton Hall University School of Law.

Disclaimer

The views, opinions and positions expressed within all posts are those of the author alone and do not represent those of the Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement (PCCE) or of New York University School of Law. PCCE makes no representations as to the accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made on this site and will not be liable for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.