A change in banks’ status may be right around the corner. Traditionally, banks have been considered “special” among financial intermediaries. This status in turn has been seen as justifying the backing of bank activities by a publicly-supported financial safety net. The recent wave of innovations in financial services, however, raises the question of whether that assessment is still valid. Many financial services traditionally offered only by banks are now increasingly being offered by other providers, often in more convenient forms for customers and sometimes also more cheaply. The economic functions performed by banks are being unbundled and offered separately or in rebundled form. To paraphrase a widely-used statement attributed to Bill Gates, while banking is needed, banks might not be.

This post draws on a recent article[1] that addresses the question whether Fintech, defined as the combination of finance and technology to provide financial services, is making banks less “special.” While not a new phenomenon, the pace of change of Fintech has appeared to have quickened recently, especially as digital infrastructure has been more widely deployed and devices like smart phones provide ever-present access to financial services. The number of Fintech initiatives has multiplied over the past few years, with some scaling up quickly. These initiatives provide financial services in innovative ways, and several of them overlap with the set of services traditionally offered by banks.

The Perception of Banks as “Special”

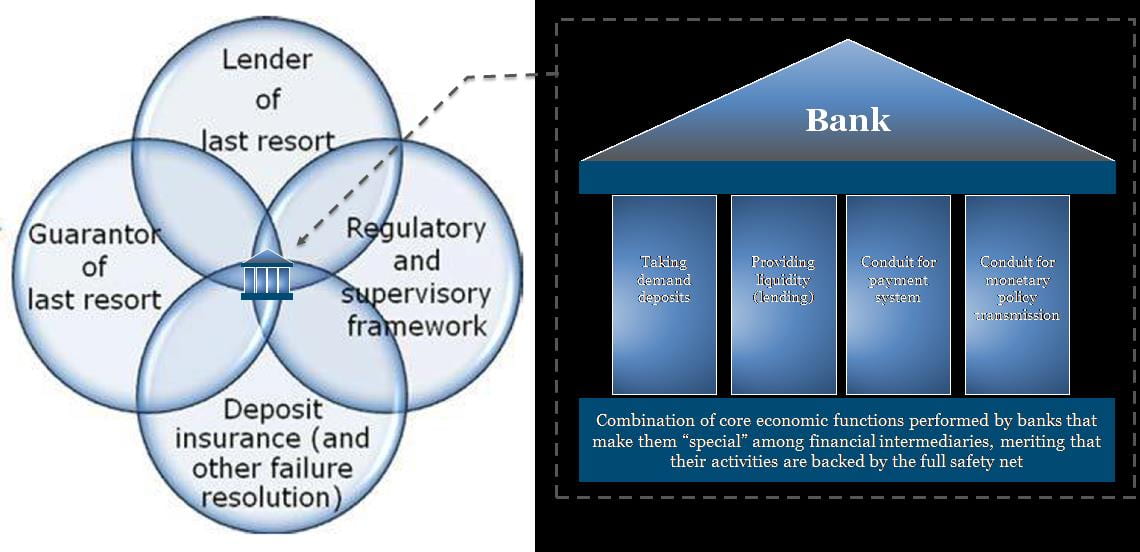

The specific bases for the view that banks are “special” have evolved over time, but generally, they turn on the specific combination of economic functions performed by banks as opposed to any particular function. This combination of functions includes, first, offering checking accounts redeemable in cash on demand; second, providing liquidity; and third, serving as conduits for payments and monetary policy transmission.

Because of their perceived “specialness,” banks have received the full set of protections afforded by the financial safety net. Traditionally, that safety net consisted of a lender of last resort and a deposit insurance function, counterbalanced by a regulatory and supervisory framework. The policy response to the recent global financial crisis effectively was to make more explicitly available the government-supported function of guarantor of last resort, thus de facto changing the design of the financial safety net. Governments and central banks provided a wide range of explicit guarantees for the liabilities—and sometimes assets—of banks. As a result of these interventions, a fourth function—governments and central banks—became a part of the financial safety net backing the activities of the banking sector in particular.

Threats to Banks’ Status: Fintech and Central Bank Digital Currencies

Recent developments suggest, however, that almost all of the individual economic functions performed by banks can in fact be provided in unbundled form by Fintech initiatives, in some cases more rapidly, at lower fees, and via more streamlined digital interfaces. In fact, Fintech initiatives are engaged in many of the same activities as commercial banks, with two major exceptions: maturity transformation, which involves taking deposits redeemable in cash on demand (and at par) and on lending them; and serving as conduits for the transmission of monetary policy. With respect to maturity transformation, the design of crypto assets seems to challenge the notion that banks are unique providers of that function. In fact, some digital tokens that are also called stablecoins are issued by individuals borrowing, that is they receive them in exchange for promises to pay them back in the future, with these promises in turn backed by individual pledging collateral). By contrast, with respect to the monetary policy transmission function, even though emergency liquidity facilities and subsequent quantitative easing polices have been targeted in part at non-bank financial institutions, policy makers and central bankers have conceptually reserved a privileged role for banks.

The introduction of a public, central bank digital currency (“CBDC”) could potentially constitute a significant challenge to the role of banks in performing the economic function of monetary policy transmission. Conceptually, issuance of CBDC might very well disrupt the current fractional reserve system. So far, while many central banks study the option and potential modalities of issuing a central bank digital currency, very few are seriously considering doing so.[2] In fact, most central banks rely on the capacity of the banking system to create money and provide the economy with adequate liquidity and, despite occasional financial crises, have concluded that the efficiency of the current system outweighs the associated costs.

Some Element of Circularity in the Reasoning

Banks’ access to all provisions of the financial safety net ensures that they are able to effectively perform some of their core characteristic economic functions. The performance of these core economic functions in turn ensures that banks remain “special” among financial intermediaries. It is obvious that there is an important element of circularity in this assessment. This circularity is appreciated by policy makers, who nevertheless maintain that the privileged access of banks to the financial safety net is warranted for two primary reasons: first, the risk of runs created by the combined effect of deposit-taking and maturity transformation, that is, by taking deposits that are withdrawable on demand at par while also providing liquidity to other entities; second, the need to ensure the integrity of the transmission mechanism of monetary policy, in which incumbent banks play a crucial role. For now, despite recent Fintech developments and conceptual considerations regarding CBDC, policymakers have effectively confirmed the “special” status of banks.

Collaboration as a Solution

With these threats to their status looming, banks nonetheless are pursuing creative strategies to counteract the effects of the unbundling of many of their economic functions. Bank profits are under pressure as new entities, unencumbered by legacy cost bases, provide similar services more cheaply and conveniently. One typical response of banks consists of collaborating with new entrants. Collaborations between banks and Fintech initiatives have taken various forms, including contractual relationships, partnerships, and acquisitions. A distinction is often drawn in this context between supposedly smaller Fintech initiatives and large technology-focused firms intent on offering financial services, with the latter being perceived as potentially more confrontational towards banks. For example, Facebook’s proposal for Libra in mid-2019, which was met with immediate and strong pushback from public authorities, was remarkable for not having involved a single bank in its consortium. That said, more recently, in November 2019, Citigroup and Google announced a partnership to offer smart checking accounts through Google Pay. Whatever the exact form the various collaborative efforts take, an important question for regulators remains to what extent collaboration provides Fintech initiatives with indirect or direct access to certain safety net provisions, and whether those initiatives are paying an adequate premium for such access.

Figure: The core economic functions that make banks “special” and justify backing by all safety net provisions

[1] Sebastian Schich, Do Fintech and Cryptocurrency Initiatives Make Banks Less Special?, 9 Bus. & Econ. Res. 89 (2019).

[2] Christian Barontini & Henry Holden, Proceeding with Caution – A Survey on Central Bank Digital Currency (Bank for Int’l Settlements, BIS Papers No. 101, 2019) (PDF 1.12 MB).

Dr. Sebastian Schich is a senior economist in the Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and supports the work of the OECD’s Committee on Financial Markets.

Disclaimer

The views, opinions and positions expressed within all posts are those of the author alone and do not represent those of the Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement (PCCE) or of New York University School of Law. PCCE makes no representations as to the accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made on this site and will not be liable for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with the author.