The following is the third post in a series of three on recent SEC enforcement. The full report can be accessed here. A note of caution to the readers: the SEC does not share enforcement data. All three posts are based on a database of SEC enforcement actions I have put together along with several research assistants, covering the period between 2007 and 2017. The data was collected by hand, and reviewed at least once. Entries were compared with SEC releases and reports, but the chance of error remains.

Litigation Venue

The Dodd-Frank Act authorized the SEC to bring almost any enforcement action in an administrative proceeding. Before Dodd-Frank, the SEC could secure civil fines against registered broker-dealers and investment advisers in administrative proceedings, but had to sue in court non-registered firms and individuals, including public companies and executives charged with accounting fraud, as well as traders charged with insider trading violations. After the Dodd-Frank amendment, save for a few remedies that can only be obtained in court, the SEC can choose the forum in which it prosecutes enforcement actions.

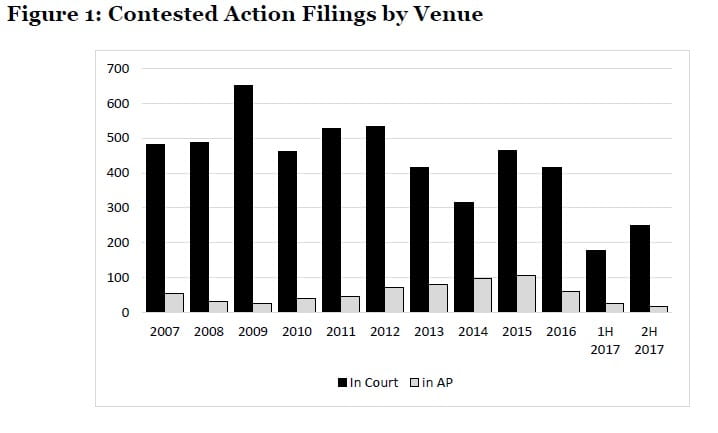

The SEC waited until 2013 but then moved quite aggressively to litigate a larger share of contested enforcement actions before administrative law judges (“ALJs”). That move has been controversial, leading to challenges on the basis of constitutional infirmities and allegations of bias by in-house judges. The charges of bias could not be sustained, but the U.S. Supreme Court is likely to reach as decide on the constitutionality of ALJ appointments soon.

But that decision may not make much of a difference for securities defendants. Facing significant pushback, the Commission started pulling back in 2015 and has since filed a larger share of contested cases in court (see Figure 1). By the second half of 2017, the SEC reverted completely, filing only 6% of contested actions in administrative proceedings, as few as it did in 2008 and 2009, well before the statutory change that sparked the controversy.

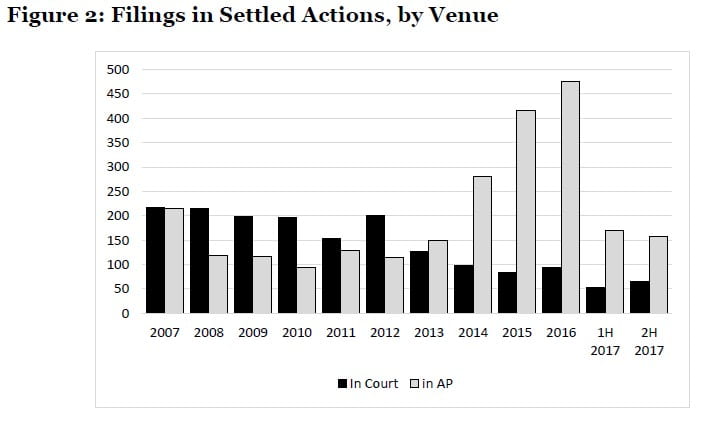

But that does not imply that the Dodd-Frank amendment has had no impact; its effects are apparent in cases that are settled (see Figure 2). Before 2011, the SEC filed about 40% of settled cases in administrative proceedings; that figure climbed to 83% in 2015 and 2016. In the second half of 2017, 71% of settled cases were filed in administrative proceedings, considerably more than before the amendment.

The rationale for giving the SEC the choice of venue was to streamline enforcement. Its effect, as currently deployed, is that defendants who contest charges in standalone actions face the SEC in court. Settlements, on the other hand, are concluded in administrative proceedings. Both the SEC and settling respondents prefer to settle in the administrative proceeding because such settlements avoid judicial oversight and the risk of litigation if a judge were to reject the proposed settlement.

Notes:

- The unit of analysis is each defendant, not an enforcement action.

- Figures 1 and 2 include only standalone actions. Follow-on and delinquent actions are always filed in administrative proceedings, and are not included.

Urska Velikonja is a professor of law at Georgetown University Law Center.

Disclaimer

The views, opinions and positions expressed within all posts are those of the author alone and do not represent those of the Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement or of New York University School of Law. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them.