The following is the first post in a series of three on recent SEC enforcement. The full report can be accessed here. A note of caution to the readers: the SEC does not share enforcement data. All three posts are based on a database of SEC enforcement actions I have put together along with several research assistants, covering the period between 2007 and 2017. The data was collected by hand, and reviewed at least once. Entries were compared with SEC releases and reports, but the chance of error remains.

Last week, the SEC released its enforcement report for fiscal year 2017. In it, the SEC reported moderate declines in the number of filed enforcement actions, 754 compared with 868 in fiscal year 2016, and in the total monetary penalties ordered, $3.8 billion compared with $4.1 billion in fiscal 2016. The narrative accompanying the release suggests that despite the change in SEC leadership, enforcement remains consistent.

The annual report combines enforcement under two very different administrations. That’s neither a bug nor a feature, just a characteristic of reports that are prepared annually. But the effect is to obscure changes that take place mid-year, such as the one that just ended.

I have previously written about the SEC’s annual enforcement statistics, or “stats” as they are lovingly called, and argued that they are invalid and unreliable measures of the SEC’s performance in enforcement: they are easy to manipulate and prone to error. At the same time, these are the performance measures used, so they are at least a starting point for analysis.

I. Overall Enforcement Activity

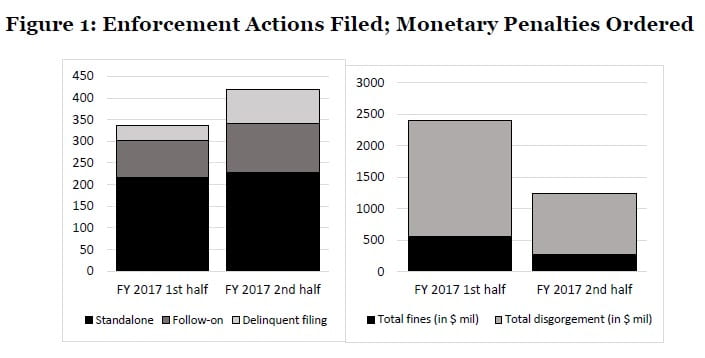

Breaking down the aggregate statistics by half year suggests that some things never change in securities enforcement, while others have changed considerably. Ordinarily, the SEC brings more cases in the second half of the year, roughly a 4o:60 ratio, and FY 2017 year is no different in this respect. As shown in the figure below, the SEC filed more cases in the second half of the year than in the first. Almost all of the difference is due to a higher number of follow-on and delinquent filing cases filed in the second half of the year. Compared with previous fiscal years, the SEC brought fewer standalone cases in 2017 than it did in 2015 and 2016, but the same number of follow-on and delinquent filing cases. The monthly distribution of cases is also consistent with long-term trends: between 1999 and 2016, the SEC filed on average 16% of all enforcement actions in September, the last month of the fiscal year. The same pattern can be observed in FY 2017.

But some things really have changed under new management. Ordinarily, the SEC obtains more monetary penalties in the second half of the fiscal year; not so in FY 2017. The SEC obtained twice as much in monetary penalties in the first half of the year as it did in the second half: $2.401 billion versus $1,248 billion.[1] Both, disgorgement orders and civil fine orders were considerably lower in the second half of the fiscal year. Moreover, almost half of $969 million in disgorgement ordered in the second half of the year came from a single enforcement action: the settlement with Swedish multinational Telia Company AB (PDF: 197 KB) for foreign bribery ($457 million).[2]

II. Enforcement Against Individual Defendants

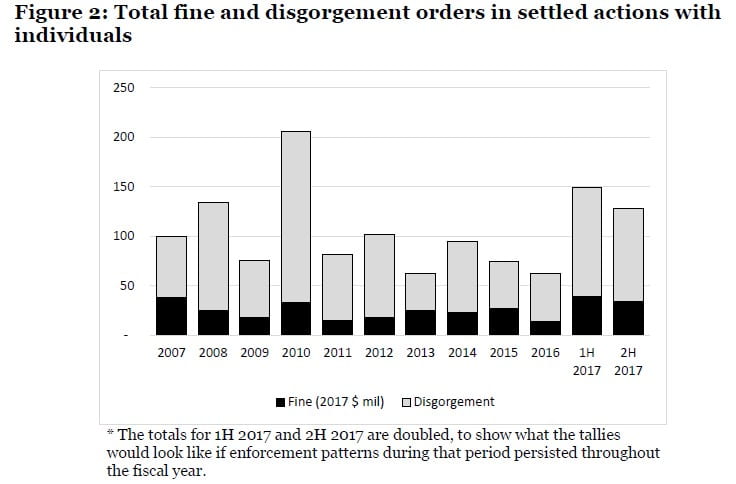

Enforcement against individual defendants has always been a significant part of SEC enforcement. Over the last ten years, individual defendants have represented a majority of defendants in SEC enforcement actions, and 2017 is no different in that regard. Measured in a variety of ways, both halves of fiscal 2017 look similar. In the aggregate, disgorgement orders and civil fines imposed against settling individual defendants were similar in both halves of 2017 (see Figure 2).

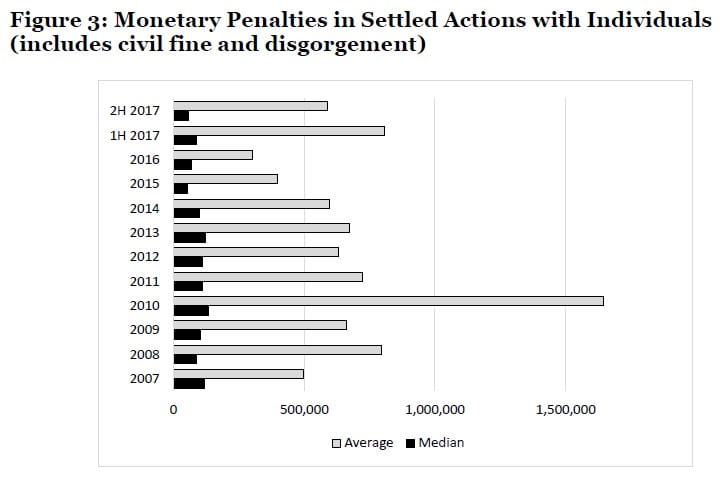

In the aggregate, the SEC filed settled actions with about 40% of defendants, consistent with the practice in 2007 to 2017. Between 2007 and 2013, individuals paid a monetary penalty in just shy of 80% of settled cases, and the median fine was about $110,000. Since then, the odds that an individual pays a monetary penalty in a settled action have increased to over 90%, but the median has declined to about $70,000 (see Figure 2).

Enforcement against individual defendants has not changed significantly since Chair White stepped down. The median monetary penalty is down somewhat, but that may be due to noise, in particular when compared with fiscal years 2014 to 2016. The SEC continues to pursue aggressively individuals for insider trading, and most cases involve clear-cut liability, not tipping rings such as those involved in the actions arising from SAC Capital and Galleon. In the second half of 2017, the SEC moved aggressively against offering fraud, pump-and-dump schemes, and the like – the sorts of cases that Chair Clayton has described as “real frauds.” Cases such as these have always been the bread and butter of SEC enforcement. They are not just securities violations but crimes; the SEC usually joins forces with prosecutors who file a criminal case against the same defendant(s), often on the same day.

Notes:

- Monetary figures are reported in 2017 dollars unless otherwise indicated.

- All monetary figures include monetary penalties imposed but deemed satisfied with payments in parallel actions.

- Except in Figure 1, only standalone actions are analyzed.

- When reporting on settlement rates, venue filings, and admissions, the unit of analysis is each defendant individual or entity, not an enforcement action.

- Median and average penalties are based on actions filed as settled actions, and use each defendant as a unit of analysis.

Footnotes

[1]. The figures on monetary penalties deviate somewhat from those reported by the SEC. There are two sources of the disagreement: (1) the data reported here do not reflect disgorgement orders against relief defendants, and (2) since the SEC does not share enforcement data, these figures were collected by hand.

[2]. The settlement credits payments to foreign and criminal authorities, so the actual payment under the SEC settlement will be reduced by as much as $248.5 million to $208.5 million.

Urska Velikonja is a Professor of Law at Georgetown University Law Center.

Disclaimer

The views, opinions and positions expressed within all posts are those of the author alone and do not represent those of the Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement or of New York University School of Law. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them.