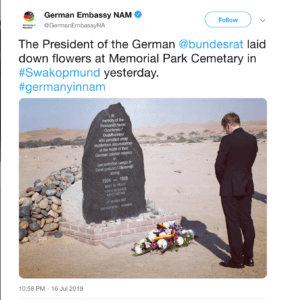

The President of the German Federal Council laid down flowers at Memorial Park Cemetary in Swakopmund yesterday.

Although this week’s post is focused on my map, I wanted to give a very recent update of how Germany talks about their genocide in present-day Naimbia without taking accountability. Behold, a recent tweet from the official German Embassy in Namibia Twitter account. In his speech, Bundesrat president Daniel Günther stated, “Even though it was not until later that the term was legally defined, the atrocities committed at the time in Germany’s name constituted what would today be called genocide.” Günther also stresses that the thousands of lives lost in the hands of the German Empire — it is something of the “past.” His words remind me that repeated semantics sans action allows countries like Germany to avoid responsibility. While the crimes were committed by a prior generation, is there not any responsibility for the new and wiser generation to right the wrongs?

While I would never compare genocides, I can compare how nation states are hold accountable for said genocides and how they take initiative to right their wrongs. From what I have learned this summer, it is clear that Germany has reacted very differently towards making amends for the atrocities of the Holocaust compared to the Herero and Namaqua genocide. (Although Black people were also victims of the Holocaust, they were not the perceived victims shown in mainstream history books, documentaries, and even museums.) To rid Berlin of public spaces that tout the National Socialist Party, streets were renamed. In contrast, the latter genocide has been left with street names of German colonialists and failed court cases asking for reparations. This comparison of the government reactions to genocides gives a glimpse of who a nation state can eventually accept as people who deserve rights. It also shows a government’s perception of how people who were wronged should be treated because of past atrocities and sets up how they should be treated going forward.

Live footage of me making connections in my head while doing research.

Before I started my research this summer, no one mentioned that it would cause me to look and feel a little like this. I am a visual learner so I have been trying trying to consolidate everything I have learned into something more digestable. So this assignment of making a map helped greatly!

In my research and for this assignment, I treated landmarks as significant events within the then-German Empire and like-minded countries. Before creating this map, I was almost deterred from creating something that would show the spatial relation between events; I thought too many of the events would be centered in Berlin. However, after creating it, I realized how many different parties were involved. My map is by no means an extensive timeline of everything related to the Afrikanische Viertel’s history, but it contains enough to help me historicize the name of streets in the neighborhood.

I love the avatar of you making connections! That’s exactly the kind of experience we’re hoping you’ll get out of the fellowship. And I also hope this is only the beginning. It’s true that you can’t really compare genocides because the systematic destruction of a population is motivated by different hatreds, strategies, and politics and is carried out in different ways (among other things). But I’m gonna try! I’d be interested in hearing if this resonates with you too. To my mind, the reason why the 1930s-1940s European Holocaust gets attention in Germany while other genocides perpetrated by the West are suppressed or denied is related to a few different factors. First, that Holocaust seemed to be targeted primarily at people who were, at first, political dissidents, and then, by some definitions (although not all), considered white. It was also targeted at people who lived in Europe, many of whom had assimilated into the European urban and elite societies and were well-connected with the British and American elite. There’s also the fact that the Jewish diaspora outside of Europe was sufficiently politically and economically powerful to put pressure on the Allies and Germany to “repair” its crimes by creating a new nation (Israel) on top of an existing one (Palestine). But even that “reparation” revealed a great deal of racist statecraft. For one thing, it denied the existence of the Palestinians. For another, it perpetuated colonialism, And for another, it resulted in Europe and the U.S. creating a “homeland” for Jews, who neither the U.S. nor Europe particularly wanted to claim, in a part of the world where the colonial project was already failing and where Jews were as unwelcome as they were everywhere else. So, ultimately, I imagine the reason why Germany does not full-throatedly acknowledge its genocide of the Herero and Namaqua is partly because no Western nation is yet willing to accept responsibility for past colonial crimes — even genocide — because each still relies on colonial and colonial-like relations today. Moreover, no Western nation (or its people) has fully accepted responsibility for racial hatred in a lasting, bone-deep, honest, materially measurable way. Indeed, millions of American whites still claim to be “color blind” and believe we are “post-racial,” even as racism is visible in every ordinary and extraordinary way imaginable. If Americans whites can’t talk about racism productively, I do wonder what we can expect of Germany. Does this sound at all accurate to you? What else can you add?

That sounds very accurate to me! Especially the part of people of a diaspora outside of the country who can advocate for reparations. The only thing I would add is the concept of expendable people. I would argue that any group of people that are targeted in a genocide are expendable in their own contexts. However, expendability also impacts the feasibility of reparations. If the ancestors of those who were exterminated are still seen as expendable years after, there is little hope for reparations. However, if the conversation and outlook of a group of people that were once expendable shifts to something positive, there is some hope for reparations.