Although I was not able to conduct an interview this week as I hoped, not all is lost. Before coming to Berlin, I did not know much about the history of German colonialism. In a way, every conversation that I have with a Berliner is an interview where I have the freedom to ask as many clarifying questions as needed.

On Wednesday I joined fellows from the Goethe Institute on a tour of the Afrikanisches Viertel. Our tour guide for the day was Christian Kopp, a historian and co-founder of Berlin Postkolonial. Usually Christian leads the tour with his colleague, Mnyaka Sururu Mboro, but Mboro was at a conference so Christian led the tour by himself. Although he has been an integral part of these tours for ten years, Christian began the tour with stating his most obvious weakness in his area of study: he’s White. His calling to do this work was not personal; instead it started on an education level and moral calling to be on the right side of history. Mboro, on the other hand, is Tanzanian and has lived in Berlin for over 30 years. His story of coming to Germany is interesting and also heartbreaking. At the age of 27, he was given the opportunity to study civil engineering in Germany. When he left, he promised his grandmother (who in turn told the whole village) that he would bring back the skull of Chief Mangi Meli. The chief was Tanzanian and executed by the German Empire in 1900 for his rebellion against the colonial rule. Mboro and Meli are from nearby places in Tanzania, a country that is now in the area that the German Empire used to call “German East Africa”.

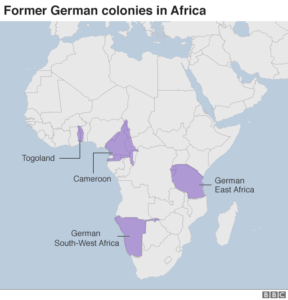

Former German colonies in Africa. Taken from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-45916150.

Forty two years later, Mboro is still on the journey to find the skull. He was told that the project to find skulls such as Chief Mangi Meli’s will be completed by the end of this year, but all he can do now is wait and hope that he can return home fulfilling his promise.

This week, the art and literature has helped give a historical context to my research. Wednesday’s tour made me wonder: Knowing the ramifications of genocide, what does it take for political parties to engage in conversations with activists in regards to renaming public spaces? Even in a country like Germany where a social-democratic party is a major political party, they have been slow to embrace the renaming of streets in the Afrikanisches Viertel. During the tour, Christian mentioned that when he met with members of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in 2008, only one out of eleven of their representatives were ready to support Berlin Postkolonial in their work. The rest were hesitant in pursuing something that was bound to have backlash amongst their constituents. Afrikanisches Viertel was never overwhelmingly African or Black, so “locals” of the neighborhood are mostly non-Black. This complicates the idea of who has the right to the city and policy decisions. If political officials ask “locals” of Afrikanisches Viertel about their opinion on renaming streets, does that mean they are engaging with those impacted by the legacy of German colonialism? I would argue no. However, despite the disappointments, perhaps it makes sense that the SPD, one of the first influenced parties in the world, felt this way. After all, Marx’s work never had a deep analysis of race.

What Germany did in Namibia to the Herero and Nama people was genocide, but not in the legal terms. While Germany stated that they were “sorry” for the genocide in 2004, it was only a sorry in the political and historical terms. There are no legal documents that have used the seemingly forbidden word: genocide. One of the fellows from the Goethe Institute echoed how often this tactic is used in the realm of politics. He is from California and mentioned how California’s governor apologized for California’s genocide against Native Americans. He called it a genocide, expressed remorse… but now what?

Recognizing their own genocide, the Herero and Nama people filed a lawsuit in 2017 that would have required Germany to pay damages over genocide and property seizures. The lawsuit further asserts that a racial extermination campaign was led by the German Empire in present-day Namibia. The lawsuit, Rukoro et al. v. Federal Republic of Germany, was denied by a U.S. judge in March of this year. The key question under consideration was whether a US federal court has jurisdiction to hear the case, brought by the indigenous people who seek compensation for their ancestors’ suffering. Before reading this court case, I did not look into a lot of legal framework around genocide and renaming of streets, but this was a great start.

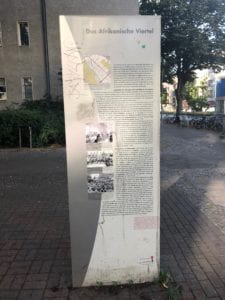

Das Afrikanische Viertel.

The most fascinating part of the tour for me was the end. Christian showed us a two-sided panel about Das Afrikanische Viertel and Das „Afrikanische Viertel“. In my eyes, it is both literature and art. The panel is two-sided to present two histories. There was no English translation because both sides presented their version of history in Germany, but I recently stumbled upon this text published by the Pro African Quarter Initiative which I believe is the text of the panel. To the best of my ability and with much thanks to DeepL, I translated the text for my own understanding. One side of the panel is the history of the Afrikanische Viertel written by the government.

Das “Afrikanische Viertel”.

The other side is the history of the “Afrikanische Viertel” written by NGOs, including Berlin Postkolonial. (Fun fact: when the panel was first unveiled, it was positioned to where one side was facing the sidewalk for everyone to read while the other side faced a tree. Guess which side was facing the sidewalk?)

While doing a literature review for my research, I often found citations to work published on Berlin Postkolonial’s website. It wasn’t until the end of Wednesday’s tour that I learned why I couldn’t access the website. It was hacked! Was it hacked by a racist or someone living in the Afrikanisches Viertel who was tired of Berlin’s colonial past being critiqued? (Another fun fact: Berlin Postkolonial isn’t beloved by everyone in the neighborhood. Just last year, Mboro was leading a tour with refugees, but it only lasted ten minutes because the neighbors called the police and 3 cars came. He is used to “locals” coming up to him and yelling racist things, but this was a step up from what he’s seen.) While it’s not known exactly who hacked the website, what everyone is sure about is that ten years worth of digitzed work was lost and ruined.

During the tour, Christian passed out some visuals about the neighborhood. I am adding them below for anyone who might be interested.

Depiction of the Berlin Conference. The man cutting the cake / Afrique is Otto von Bismarck. Photo courtesy of Berlin Postkolonial.

Togo became a German colony in 1884. The background of this stamp is the Kaiser’s yacht. Without ships and the German navy, there probably would not be German colonies in Africa. Photo courtesy of Berlin Postkolonial.

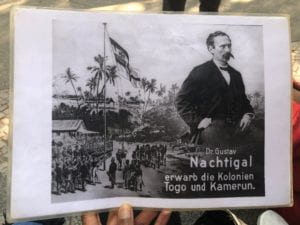

Dr. Gustav Nachtigal was sent to West Africa by Otto van Bismarck to mak contracts with African countries and ultimately to acquire colonies. This photo specifically glorifies the work he did in Togo and Cameroon. Photo courtesy of Berlin Postkolonial.

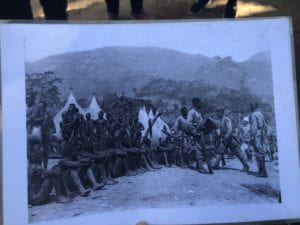

Life under the rule of the German Empire in one of their African colonies. Colony unknown. Photo taken in the early 20th century. Photo courtesy of Berlin Postkolonial.

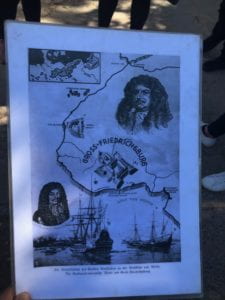

Now in present-day Ghana, this map details Groß-Friedrichsburg within the Gold Coast. Photo courtesy of Berlin Postkolonial.

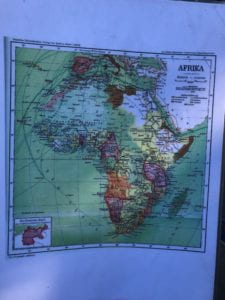

A map of Africa in the eyes of the German Empire. Photo courtesy of Berlin Postkolonial.

The interview can wait; this was obviously an extremely valuable experience for you. Do you also have the text of the NGO version of the panel, by the way? I’d be interested in reading that. I’m also curious about the history of the panel in general. Do such neighborhood history panels exist in other neighborhoods or just this one? How is it that there are two diverging histories on the panel? Was this a compromise between city government and NGOs like Berlin Postkolonial? This is particularly interesting to me for three reasons: 1) historical markers are such a major feature of Berlin as a city, unlike most, that tries to make (at least some of) its layers of history visible in contemporary interactions with the urban landscape, 2) historical markers produced by CBOs are having a little resurgence in NYC and are often used as a way for communities to “claim place” in the face of displacement pressures, 3) neighborhood signage like this has also been (unsurprisingly) co-opted by neoliberal/design-oriented city governments who are trying to make the city more “legible” to tourists or wealthy newcomers. This latter process can be a way of authenticating a neighborhood’s history as a consumer product, rather than providing the necessary investment to keep people in their homes or small businesses in their commercial spaces. So, in other words, this signage can be just as problematic as the street signs. Another quick comment: I’d like to hear more about the political or inter-ethnic tension in Afrikanische Viertel. I’d understood this as a mostly immigrant section of the city. Is the anti-Black tension coming from particular ethnic groups? What does this say about how race operates in Berlin in contrast (or comparison) with how it operates in the U.S., where, as we often say, part of immigrant assimilation involves adopting anti-Black racism?

I just emailed you the text of the panel! Happy reading and I can’t wait to hear your thoughts.

That’s an interesting question. I’ve seen a lot of panels in Berlin for historical spots such as the Berlin Wall, Tempelhof, and the earliest concentration camps, but not particularly in neighborhods. I think Afrikanisches Viertel is special. The talks of the panel started when there was a resurgence of talks to rename the streets in the neighborhood. When it became clear early on that the government was not excited to have these conversations, the idea of a panel came up. Originally, the government was charged with writing the text of the panel which would be sent to the NGOs for approval. Their first draft was horrendous, and so was their second draft. The NGOs were displeased and a compromise arose: the government and NGOs would write their two very different histories of the neighborhood and that would become the panel. Your point about neighborhood signage being co-opted by neoliberal/design-oriented city governments is what I think almost happened with this panel. Wedding has a large immigrant population and although it is centrally located, it is not very “attractive” to tourists and wealthy business owners from what I have seen. However, I don’t think the history of Afrikanische Viertel itself is what deters tourstis and investors from the neighborhood – it’s the immigrants, many of who are not Black Africans.

I’m going to continue talking to Black people in the neighborhood to understand where the anti-Black tension is coming from in the neighborhood (if at all). I do believe there is some, and my guess would be that it comes from the two largest minority groups in Berlin: Turkish and Vietnamese immigrants. Both groups primarily came to Berlin as temporary contract workers and many have settled roots here and experienced tension with Germans because of their immigration. For example, many Vietnamese people living in Berlin lost their legal residence status and job after the wall fell because they were only allowed to live in East Germany, even post-unification. For the Turkish immigrants, they were seen as outcasts in Germany and many political parties wished for them to return to Turkey. It seems as though the influx of African immigrants came a few decades after the Turkish and Vietnamese influx, so my theory as of now is that the anti-Black tension is stemming from Africans making a lot of noise because of the injustice they are experiencing. Meanwhile, for other immigrants groups, it may seem as though the injustices they went through have been overlooked while the newer immigrant group is having their concerns heard. I’m not sure if there’s a name for this, but I have seen this before in the U.S. and this might be the case here in Berlin. (And on top of this, there is a layer of good ole anti-Black racism.)