Life jackets and destroyed rubber dinghies left behind by migrants in Lesbos, Greece, in 2015. Credit Mauricio Lima for The New York Times

Every month, we round up all of these stories and then try to come up with a fun list or question that ties them all together to use as a title. This month, it seems like the best frame to put around the collection is a series of questions about how we approach our subjects such as: What stories do we tell? How do we tell them? And who do we share them with? Each piece here is valuable in its own right, but hopefully we’ll also find something more out of seeing them all together. Thanks, as always, for coming along through our journey of bookmarks and taglines.

First, and urgently, two stories about the importance of counting deaths and why they don’t get counted.

Giving a sense of scale to the catastrophic refugee crisis, German Newspaper Catalogs 33,293 Who Died Trying to Enter Europe by Alan Cowell reports at The New York Times

They were the ones who did not make it; the ones who perished seeking a new life in Europe; the ones the people smugglers consigned to frail craft doomed to founder in the Mediterranean Sea.

The German newspaper Der Tagesspiegel has sought to build a monument in print to them, cataloging the 33,293 people who, it said, died between 1993 and 2017 fleeing war, poverty and oppression in their own countries.

But, in the process, The List, as the newspaper called its 48-page tally of the lost, cast a baleful light on a tragedy that runs in parallel to the deaths: Many of them died in anonymity, particularly in recent years.

And with a devastating look at the lives lost in the US war in Iraq, The Uncounted by Azmat Khan and Anand Gopal for The New York Times.

Mohammed Tayeb al-Layla

and Dr. Fatima Habbal

Our own reporting, conducted over 18 months, shows that the air war has been significantly less precise than the coalition claims. Between April 2016 and June 2017, we visited the sites of nearly 150 airstrikes across northern Iraq, not long after ISIS was evicted from them. We toured the wreckage; we interviewed hundreds of witnesses, survivors, family members, intelligence informants and local officials; we photographed bomb fragments, scoured local news sources, identified ISIS targets in the vicinity and mapped the destruction through satellite imagery. We also visited the American air base in Qatar where the coalition directs the air campaign. There, we were given access to the main operations floor and interviewed senior commanders, intelligence officials, legal advisers and civilian-casualty assessment experts. We provided their analysts with the coordinates and date ranges of every airstrike — 103 in all — in three ISIS-controlled areas and examined their responses. The result is the first systematic, ground-based sample of airstrikes in Iraq since this latest military action began in 2014.

Next, let’s turn to current US domestic politics, first, with Rosemary R. Corbett review of Andifundamentalism in Modern America

Watt is a keenly observant commentator who effortlessly blends media analysis with intellectual history, archival work with examinations of contemporary events. His prose is engaging without sacrificing depth or rigor. Perhaps most impressively, Watt is an even-handed and even generous critic of those with whom he disagrees. When it comes to the subject of fundamentalism, such equipoise is almost astonishing. But that is part of the point. Only by ratcheting down the rhetoric can one begin to dismantle the machinery that has built the targeting of ostensible fundamentalists—particularly Muslims, and often violently—into a pillar of statecraft at home and abroad.

Next, we highly recommend Ann Neumann‘s take on Louie and Roy: The hypocrisies of the left and the right fail women for The Baffler

Contemporary iterations of purity ideology continue to shape public policy, from abstinence education that keeps young women vulnerable to the threat of pregnancy and disease, to laws that increasingly restrict access to legal abortion—rendering reproductive health care unthinkable or shameful. It’s this shaming of women for male sexual behavior that allows men to continue predatory sexual behavior without consequence. When women are responsible for male actions—as moral actors, as mothers, as victims—men get a pass and the nation remains sovereign. Instead, women bear the consequences, whether it’s single motherhood, unequal pay, or exclusion from decision-making roles in politics and the workplace.

And our regular installment of Things Ta-Nehisi Coates Is Doing on the Internet is pretty great this month: Ta-Nehisi Coates on education, religion, and Obama a conversation with Michael Eric Dyson in The Washington Post

Q: I was preaching yesterday in Chicago, and I talked about the white ministers with lots of black folk in their congregations who support Trump, like Joel Osteen and Paula White. And I said that two of our greatest writers in this generation, Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jelani Cobb, do not believe in your God, and yet you turn to them for insight that feeds your spirit. I asked the congregation if they could actually say they’ve got more in common with these white ministers who support Trump, and who undercut everything they believe in, than they do with you and Cobb. And they clearly favored you and Jelani.

A: I’m happy to see that. I don’t know how you grow up black in this country and not have tremendous respect for the church, even though I was raised outside of it. So even as I articulate my beliefs, I try to be really respectful. I’m happy that it’s received. I often wonder what is the place where the two things cross? Am I drawing some sort of conclusion, or some sort of feeling, that folks get in church anyway, regardless of their belief in Jesus Christ as their savior? Is there a route that they’re traveling in their religion that leads to a similar place that I go, even with my lack of religion?

The New Yorker featured a couple of useful glimpses into right wing politics this month, first with Birth of a White Supremacist: Mike Enoch’s transformation from leftist contrarian to nationalist shock jock by Andrew Marantz

In the early days, “The Daily Shoah” reserved most of its firepower for its neighbors on the political spectrum, mocking those on the alt-right who reduced all geopolitical issues to a simple Zionist conspiracy. With each episode, though, the co-hosts’ anti-Semitism sounded more sincere. Allusions to gas chambers and ovens became almost a verbal tic. Whenever the co-hosts mentioned a Jewish journalist or politician, they would emphasize the name, pronouncing it in a nasal accent and using a reverb effect. This invention—the Echo, they called it—became one of their signature memes. They approximated it in writing, in the blog and on Twitter, surrounding Jewish names with triple parentheses.

Then, in January, 2015, Enoch read “The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements,” by Kevin MacDonald, a former psychology professor at California State University, Long Beach. The book—published in 1998, heavily footnoted, and roundly debunked by mainstream social scientists—is a touchstone of contemporary intellectualized anti-Semitism. On “The Daily Shoah,” Enoch called it “important and devastating, something I urge everybody to read,” and then offered even higher praise: “It triggered me so hard.” From then on, he began to express his anti-Semitism more frankly. He sometimes spun his Northeastern upbringing as an advantage: having grown up around Jews, he understood the enemy. “You’ll talk to white Americans today, and they don’t actually know if someone’s Jewish or not,” he said. “I have very honed Jewdar. I can tell.”

And second with Jane Mayer‘s The Danger of President Pence

There have been other evangelical Christians in the White House, including Carter and George W. Bush, but Pence’s fundamentalism exceeds theirs. In 2002, he declared that “educators around America must teach evolution not as fact but as theory,” alongside such theories as intelligent design, which argues that life on Earth is too complex to have emerged through random mutation. Pence has described intelligent design as the only “remotely rational explanation for the known universe.” At the White House, Pence has been hosting a Bible-study group for Cabinet officers, led by an evangelical pastor named Ralph Drollinger. In 2004, Drollinger, whose organization, Capitol Ministries, specializes in proselytizing to elected officials, stirred protests from female legislators in California, where he was then preaching, after he wrote, “Women with children at home, who either serve in public office, or are employed on the outside, pursue a path that contradicts God’s revealed design for them. It is a sin.” Drollinger describes Catholicism as “a false religion,” calls homosexuality “a sin,” and believes that a wife must “submit” to her husband. Several Trump Cabinet officials have reportedly attended the Bible-study group, including DeVos, Pompeo, and Attorney General Jeff Sessions. In a recent interview with the Christian Broadcast Network, Drollinger said that Pence “has uncompromising Biblical tenacity” and “brings real value to the head of the nation.”

And in LitHub another helpful dispatch: Science vs. Religion: Travels in the Great American Divide Dinty W. Moore Tries to Find the Mythical Middle Ground in LitHub

For the past year, I’ve been part of a project titled Think Write Publish: Science & Religion, an attempt to use the tools of creative nonfiction to explore the idea that faith and rationality can coexist just nicely, thank you, despite various brouhahas over where we came from, how we got here, and whether the human species is or is not in the process of destroying the planet.

As of late, thanks no doubt to a horrifically contentious election cycle pockmarked by extended, often hyperbolic skirmishes over both science and religion, Americans appear even more divided, locked away in separate, seemingly incompatible camps. That’s the dominant narrative in the media, at least, but my instinct is that it can’t be quite so simple as all that. I’m guessing the truth of it all is more complex, less predictable.

Which led me to Ravenswood, and to other small towns in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and central Ohio, where I had a series of conversations with so-called “real” Americans: folks outside of politics and professional punditry, and apart from the expert, analytical academic bubble where I—a tenured professor, professional skeptic, and inveterate agnostic—spend most of my time.

I wanted to speak to people who were neither steeped in political rhetoric nor provoked into shouting by the presence of television cameras, and my questions were as simple as I could make them: Is the rift between those who favor science and those who follow religion as real and as wide as some suggest? Is there room for more complex, more nuanced views? If so, what do they look like?

Which got us thinking, as we often do, about how academics are engaging with audiences outside of the academy. We especially appreciate these two takes:

First, Adam Kotkso arguing that Public Engagement Is a Two-Way Street: Claiming that academics are failing to engage with the general public is intellectual laziness at best and anti-intellectual posturing at worst in the Chronicle of Higher Education

Claiming that academics are failing to engage with the general public is intellectual laziness at best and anti-intellectual posturing at worst. And that brings me to my second reaction, which is to ask exactly which public we are supposed to engage with. Is it the public that is not willing to run a simple Google search before declaring that public-facing academic work does not exist? Is it the public that so devalues the work of teaching that it doesn’t even occur to them to think of it as a form of public engagement? Or do they have in mind the public that tolerates ever-shrinking public support for higher education and turns a blind eye to the destruction of the profession through adjunctification?

And second, Alan Jacobs asking: Can Evangelicals and Academics Talk to Each Other?: A professor and evangelical Christian on the pervasive misunderstandings between the two groups and how to correct them for The Wall Street Journal (paywalled)

Last year, as the fire and fury of the presidential election were intensifying and people all around me were growing more and more hostile to one another, I was struck by the familiarity of the situation. For all my adult life, I’ve been dealing with the kinds of hostilities and misunderstandings that now dominate American politics, because I belong to two very different and mutually suspicious groups. I am an academic, but I am also an evangelical Christian.

While, within the tower itself, Jon Baskin takes a deep dive look at the influence of one scholar in particular, The Disillusionment of Samuel Moyn: The Yale historian has become a prominent critic of liberalism. But what’s he for? for The Chronicle of Higher Education

While, within the tower itself, Jon Baskin takes a deep dive look at the influence of one scholar in particular, The Disillusionment of Samuel Moyn: The Yale historian has become a prominent critic of liberalism. But what’s he for? for The Chronicle of Higher Education

The beard Moyn had grown the second time we met, at a diner in Manhattan in the summer, did not make him look any older. It did add a hint of rabbinical authority, which seemed appropriate given that Moyn was in town for a conference on the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. Religion is another topic Moyn knows a lot about — his most recent book, published in 2015, is about the Christian roots of human-rights discourse. Our conversation, however, focused on the prospects of political reformation: Where does Moyn think we should go next?

And lastly, a chance to read some really excellent public-academic work published by The Immanent Frame in its new series Recovering the Immanentist Tradition with work by the likes of Laura Levitt, Eboni Marshall Turman, Joseph Blankholm, and others.

The purpose of this forum is to recover a different way of understanding terms such as “immanence,” “naturalism,” “materialism,” and “monism” in order to overcome their parasitic, negative relationship with religious premises and thus shed the negative connotations they have accreted in Christian-centered Western thought. We want, in other words, to reconstruct a positive way of imagining irreligion, on its own terms.

When it comes to writing about religion for public audiences, one would always be wise to heed the advice of Hussein Rashid who wrote this month about the 10 Commandments on Reporting on Islam on Medium

Over the last several years I have been offering a critique of media coverage of Islam and Muslims, and after a decade of doing so, it seems like a good time to offer a summation of what I say in nearly every article. This piece can serve as a handy reference for writers who want to cover Muslims, and perhaps save me from writing the same piece ad nauseam.

And we loved seeing this piece about Sahar Ullah‘s great public-intellectual work in Serena Kutchinsky‘s look at How to make good jokes about the hijab: A Muslim playwright shares her thoughts on turning a religious symbol into comedy gold for the BBC

Sahar has become a myth-busting voice for a minority whose views are seldom heard. But she’s wary of being seen as representative of a broader Muslim identity. For her, the hijab was a personal choice she made in her mid-teens. “It was something I wanted to do but I was afraid of how people would react. Between the ages of 13 and 15, you want to be accepted, so why would you do something that makes you so different?

“I ended up making friends with people who were into alternative music and liked things that were different, so when I started wearing the headscarf they were really excited. Some people made fun of me, but it didn’t last, as my friends would intervene.”

Those reactions to the hijab – whether of excitement or mockery – are what the Hijabi Monologues explore.

“Just like race, the hijab is part of your identity because it’s visible. People respond a certain way to it and that is part of my lived experience.”

The reality is that for those who wear the hijab, it’s often not a big deal. “One of our performers always says that she is passionately dispassionate about the hijab, that she wears it like she wears her underwear.” It’s other people’s reactions that can make it problematic.

Her writing focuses on the paradox of feeling both invisible and hyper-visible in the hijab.

Which is a great segue to Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan‘s post on Islamophobia is not a “phobia”, it’s a way of governing for her blog The Brown Hijabi

For starters, I think the word “Islamophobia” itself can lead to misunderstanding. Unlike claustrophobia or arachnophobia, Islamophobia needs to be understood beyond individual irrational fear of Islam or Muslims. Raising awareness of Islamophobia that puts too much emphasis on individual fear, prejudice or violence is actually, in my opinion, unhelpful. Whilst we do need to bring more attention to street harassment caused by Islamophobia – and I remain consistently antagonised by feminists who continue to be silent on the issue of gendered Islamophobic violence and assault – I believe we also need to understand such acts of violence as more than interpersonal prejudice. Reduction of Islamophobia to “phobia” and prejudice enables people to feel they have no connection to and are not invested in Islamophobia. It enables a false understanding of Islamophobia. Islamophobia is not a phobia, it is a structural and state-sanctioned way of governing.

And Wajahat Ali published this moving op-ed in The New York Times: I Want ‘Allahu Akbar’ Back

I’m 37 years old. In all those years, I, like an overwhelming majority of Muslims, have never uttered “Allahu akbar” before or after committing a violent act. Unfortunately, terrorists like ISIS and Al Qaeda and their sympathizers, who represent a tiny fraction of Muslims, have. In the public imagination, this has given the phrase meaning that’s impossible to square with what it represents in my daily life.

Next, back to more public-academic writing with the excellent Jesus the Aryan: Susannah Heschel on the Reformation’s Troubling Legacy for The Marginalia Review of Books

Theological bulimia enacts a myth with long roots in Western culture. Kronos, fearing the prophecy that his children would overthrow him, swallowed them all except Zeus, and when Zeus grew up he overthrew his father, forcing Kronos to vomit up all the siblings he had swallowed. Kronos, through his regurgitation, restored his children. In the case of Christianity, however, it is the child (Christianity) devouring and vomiting the parent (Judaism), purging itself of the Jewish mother whose presence can never be fully eradicated from Christian theology. The bulimia metaphor captures the deeper conflict within Christian theology, deriving religious identity from the mother religion and yet needing to differentiate from the mother in order to achieve a separate, independent identity. The Christian cannibalization of Judaism safeguards the Jewish through its introjection into Christianity, but the Jewish is later rejected through an attempted theological regurgitation. While the regurgitation can eliminate certain aspects of Jewish presence – such as the Old Testament – it can never erase the memory of the initial birth of Christianity within Judaism, and it is that memory that remains forever haunting.

Elsewhere in Jewish studies, Julia Watts Belser wrote this excellent piece on Disability Studies and Rabbinic Resistance to the Roman Conquest of Jerusalem for the Ancient Jew Review

In antiquity as in modernity, imperial ideology makes frequent use of disability and physical impairment to imagine and refashion the colonized subject. In the cultural grammar of conquest, defeat disables the nation. War itself is indelibly intertwined with disability.[1] Warfare operates through the deliberate production of disability, as the bodies of combatants come to be killed, to bear wounds, to be maimed. Even beyond the ordinary facts of battle, the symbolic discourse of conquest is bound up with disablement. Victors often subjugate the bodies of the conquered through calculated acts of mutilation, through the intentional production of impairment. Wounded, marked, and disabled bodies make tangible the brutal incursions of imperial power. Imperial conquest produces disability, both as a material reality and as a discursive effect. But the victors do not have the final word. In rabbinic narrative, the subjugated body becomes a potent site of resistance, a site for grappling with trauma and violation—a site through which rabbinic storytellers flip the script about disability to challenge Roman dominance over the Jewish body.[2]

And then there’s the beautiful Primed for Mysticism and Scared to Death: A writer reckons with Judaism, the writing life, and the allure of fundamentalism by Arielle Angel for Guernica

I admit that I’m attracted to artists and to stories about artists. In a certain sense, though it shames me, I have trouble fathoming what other people do, how they organize their lives, how they make meaning from its evident meaninglessness.

The more I learned about Chabad Hasidim, set up on American city street corners and in far-flung posts around the world—a uniformed, self-proclaimed army of truth and light—the more I identified with their spiritual orientation, their irrefusable sense of duty. The more I identified with their non-civilianness.

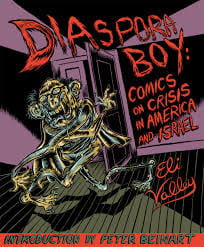

And, as big fans of Eli Valley‘s work, we were very excited to read this interview with him by Nathan Goldman for the Los Angeles Review of Books: Redefining Jewish Authenticity

But even if the comics are hyperbolic and insane, I have very serious intentions with them, and I do aspire to the trajectory of Jewish literary and intellectual culture. And I know it’s a glib answer, but when people ask me who my readership is, the obvious answer is me and my friends, but the longer answer is ghosts from the past and ghosts from the future. As far as the past, I’m mesmerized by the kinds of writings and cultural output that was being created in Central Europe in the early 20th century, and I like to think that my comics are a reflection of and a debate with that. As for the future, who knows what’s going to happen — especially these days — but I like to think that future grad students will be looking at this book, along with a lot of other stuff, in order to figure out what the hell was going on (to paraphrase our horrible nightmare man in charge right now).

But even if the comics are hyperbolic and insane, I have very serious intentions with them, and I do aspire to the trajectory of Jewish literary and intellectual culture. And I know it’s a glib answer, but when people ask me who my readership is, the obvious answer is me and my friends, but the longer answer is ghosts from the past and ghosts from the future. As far as the past, I’m mesmerized by the kinds of writings and cultural output that was being created in Central Europe in the early 20th century, and I like to think that my comics are a reflection of and a debate with that. As for the future, who knows what’s going to happen — especially these days — but I like to think that future grad students will be looking at this book, along with a lot of other stuff, in order to figure out what the hell was going on (to paraphrase our horrible nightmare man in charge right now).

That’s very arrogant, obviously, but it’s not like I mean it to be literal. It’s just a reflection of how seriously I take this work, despite the seeming reckless glibness of the comics themselves.

And one last Judaism item for the month, a fun piece on The Wire That Transforms Much of Manhattan Into One Big, Symbolic Home by Michael Inscoe for Atlas Obscura

Every Thursday and Friday morning, Rabbi Moshe Tauber leaves his home in Rockland County, New York, at about 3:30 a.m. He arrives in Manhattan an hour later and drives the 20-mile length of a nearly invisible series of wires that surrounds most of the borough. He starts at 126th Street in Harlem and drives down, hugging the Hudson River most of the way, to Battery Park and back up along the East River, marking in a small notebook where he notices breaks in the line. Known as an eruv, the wire is a symbolic boundary that allows observant Jews to carry out a range of ordinary activities otherwise forbidden on the Shabbat.

Okay, how about some Christian news now? You know the grotesquely rich guy who just shut down Gothamist and DNA Info because they workers voted to unionize? Well, check this out: Joe Ricketts’ passion project, a 931-acre religious retreat on the Platte, has a chapel, 7 lodges and a 2,500-foot walk by Hailey Konnath for the Omaha World-Herald

“I think it’s kind of healthy for people to think ‘Who am I? What am I? Why am I here? What are the most important things to me in my life, and what are the least important things in my life?’ ” Ricketts said. “You need that environment that leads to contemplation in order to work.”

Next, let’s Meet The “Young Saints” Of Bethel Who Go To College To Perform Miracles by Molly Hensley-Clancy at Buzzfeed

The basic theological premise of the School of Supernatural Ministry is this: that the miracles of biblical times — the parted seas and burning bushes and water into wine — did not end in biblical times, and the miracle workers did not die out with Jesus’s earliest disciples. In the modern day, prophets and healers don’t just walk among us, they are us.

To Bethel students, learning, seeing, and performing these “signs and wonders” — be it prophesying about things to come or healing the incurable — aren’t just quirks or side projects of Christianity. They are, in fact, its very center.

Next up: She led Trump to Christ: The rise of the televangelist who advises the White House by Julia Duin for The Washington Post

White has no title and no official position at the White House but plays several roles. After helping to put together an evangelical council for Trump during the campaign, she is now, she explains to me, the convener and de facto head of a group of about 35 evangelical pastors, activists and heads of Christian organizations who advise Trump. (The White House would not release a list of members, but other names associated with this group include Focus on the Family founder James Dobson, Billy Graham’s son Franklin Graham, Liberty University President Jerry Falwell Jr., conservative political activist Ralph Reed and Dallas-based pastor Robert Jeffress.) She also acts as pastor to the president. And in the words of Johnnie Moore, the evangelical advisory council’s unofficial spokesman and White’s publicist, she serves as “part life coach, part pastor” for White House staff.

And someone else to meet:The Passion of David Bazan: At the Cornerstone Christian rock festival, a fallen evangelical returns to sing about why he broke up with God. by Jessica Hopper for The Chicago Reader

“People used to compare him to Jesus,” says a backstage manager as David Bazan walks offstage, guitar in hand. “But not so much anymore.”

It’s Thursday, July 2, and Bazan has just finished his set at Cornerstone, the annual Christian music festival held on a farm near Bushnell, Illinois. He hasn’t betrayed his crowd the way Dylan did when he went electric—this is something very different. The kids filling the 1,500-capacity tent know their Jesus from their Judas. There was a time when Bazan’s fans believed he was speaking, or rather singing, the Word. Not so much anymore.

Meanwhile, over in Catholicism:

Boy are we excited for The Costume Institute Takes On Catholicism by Vanessa Friedman for The New York Times

“Every show we do at the Costume Institute has that potential,” said Andrew Bolton, the curator in charge. “This one perhaps more than any other. But the focus is on a shared hypothesis about what we call the Catholic imagination and the way it has engaged artists and designers and shaped their approach to creativity, as opposed to any kind of theology or sociology. Beauty has often been a bridge between believers and unbelievers.”

Left: El Greco, Cardinal Fernando Niño de Guevara, circa 1600. Right: Cristobal Balenciaga evening coat, fall 1954–55. Credit Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Metropolitan Museum/digital composite by Katerina Jebb

Also, The war against Pope Francis: His modesty and humility have made him a popular figure around the world. But inside the church, his reforms have infuriated conservatives and sparked a revolt in The Guardian

Pope Francis is one of the most hated men in the world today. Those who hate him most are not atheists, or protestants, or Muslims, but some of his own followers. Outside the church he is hugely popular as a figure of almost ostentatious modesty and humility. From the moment that Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio became pope in 2013, his gestures caught the world’s imagination: the new pope drove a Fiat, carried his own bags and settled his own bills in hotels; he asked, of gay people, “Who am I to judge?” and washed the feet of Muslim women refugees.

But within the church, Francis has provoked a ferocious backlash from conservatives who fear that this spirit will divide the church, and could even shatter it. This summer, one prominent English priest said to me: “We can’t wait for him to die. It’s unprintable what we say in private. Whenever two priests meet, they talk about how awful Bergoglio is … he’s like Caligula: if he had a horse, he’d make him cardinal.” Of course, after 10 minutes of fluent complaint, he added: “You mustn’t print any of this, or I’ll be sacked.”

And the beautiful and tragic piece by Dan Barry for The New York Times: The Lost Children of Tuam

The Tuam case incited furious condemnation of a Catholic Church already weakened by a litany of sexual abuse scandals. Others countered that the sisters of Bon Secours had essentially been subcontractors of the Irish state.

But laying the blame entirely on the church or the state seemed too simple — perhaps even too convenient. After all, many of these abandoned children had fathers and grandparents and aunts and uncles.

The bitter truth was that the mother and baby homes mirrored the Mother Ireland of the time.

Lastly, Religious Leaders Gather to Bless Texas Abortion Clinic: Amid pending litigation over anti-abortion laws, local clergy sang songs and prayed at Whole Woman’s Health in Fort Worth in Thursday by Sophie Novack at The Texas Observer

Anti-abortion advocacy is often inextricably tied to religion, but reproductive rights advocates want to counter that narrative. Late Thursday, clergy gathered at the Whole Woman’s Health abortion clinic in Fort Worth to bless the providers, clinic staff and patients. They sang “Hallelujah.” They prayed.

We admit it, we’re kind of obsessed with witches right now, but we are so not alone:

First, may we all, in every and any form, praise Lindy West, for writing things like Yes, This Is a Witch Hunt. I’m a Witch and I’m Hunting You for The New York Times

When Allen and other men warn of “a witch hunt atmosphere, a Salem atmosphere” what they mean is an atmosphere in which they’re expected to comport themselves with the care, consideration and fear of consequences that the rest of us call basic professionalism and respect for shared humanity. On some level, to some men — and you can call me a hysteric but I am done mincing words on this — there is no injustice quite so unnaturally, viscerally grotesque as a white man being fired.

We know we’re not the only ones always excited to debate this question: Why the Witch Is the Pop-Culture Heroine We Need Right Now by Kathryn VanArendonk for Vulture

The magic of the witch in this particular moment is that both the traditional, villainous witch and her feminist, heroic opposite are equally alive in the cultural consciousness. Of course, the pervasiveness of the evil witch is what gives the newer interpretation its vigor: Even when we try to divorce the witch from any direct implication of injury — when a coven comes together as a self-contained group, a safe community apart from the rest of the world — the traditional vision of witchcraft still lurks in the air. Women gathering together to perform spells? Women gathering to share information in the dark of night? Women gathering? Whether you call it witchcraft or you call it a feminist book club, it will always feel a bit dangerous. Thinking of the witch as a protagonist rather than a villain feels subversive and gutsy when so few women, in fiction or in life, get to hold actual positions of power.

Another good question: What sparked our fear of witches — and what kept it burning so long? by Brunonia Barry for The Washington Post

“The Witch” is an important work, representing more than 20 years of scholarly research. Though not a casual read, for anyone researching the subject, this is the book you’ve been waiting for, one that lays to rest many conflicting theories that emerged in the latter part of the 20th century. It provides a social, historical and religious continuum based on impeccable research. But “The Witch” is more than a historical reference; it’s also a cautionary tale. In Hutton’s words, witch hunts remain “a very live issue in the present world, and one that may well be worsening.” In these tumultuous times, we would do well to learn from the history Hutton depicts.

And another bewitching item: Boring Sarah Is the True Villain of ‘The Craft’: “The Craft” is a story about a trio of chill and fun witches who are minding their own business and casting spells, only to have their fun ruined by an anti-feminist wet blanket by Alana Massey for Broadly.

The thing about The Craft is that its central theme is overwhelmingly common in culture: Girls who attain a modicum of power are inherently untrustworthy and dangerous. What’s disappointing is that our sentimentality for the era and film creates a collective amnesia about what actually happens in the movie, which is misguidedly hailed as subversive feminist cinema. So the next time a friend suggests watching it for nostalgia or whatever, gently decline and suggest almost anything else that actually serves to empower women. Hell, you could even watch The Rugrats.Three-year-old Angelica was a more exemplary witch than the one you’ll find in The Craft.

An excellent report on how Trans and Intersex Witches Are Casting Out the Gender Binary by Lewis Wallace for them.

A growing movement of trans and queer people in the U.S. engaging with paganism and magic makes sense on its face: queer and trans people are often pushed out of our communities of origin, and even the more progressive wings of Christianity are only barely starting to engage with trans issues. Magic and witchery are easy to claim, and they are also associated with a resistance to Christian hegemony. But as I talked to trans people around the country about their magic practices, I also realized there is more to this trans magic revival than the fact that it’s a convenient alternative to institutions that reject us.

And we really want to go see this! North America’s Largest Witchcraft Collection Has Its First Major Exhibition: The first major exhibit on the Cornell University Witchcraft Collection opens Halloween, and explores the persecution of women through its historic objects by Allison Meier for Hyperallergic

Cornell University’s cofounder Andrew Dickson White was a huge bibliophile. With his librarian George Lincoln Burr, he amassed a formidable collection of books, with a special concentration on those that highlighted historic persecution and the experiences of the downtrodden. Out of this personal library came the Cornell University Witchcraft Collection, which holds over 3,000 objects on superstition and witchcraft in Europe, mostly acquired in the 1880s.

“He was interested in people on the margin and the underside of history, so another big collection that he acquired was the anti-slavery collection,” Anne R. Kenney told Hyperallergic. Kenney stepped down as university librarian earlier this year, and said that she wanted to cap off her career at Cornell with an exhibition on the Witchcraft Collection and its connection to women’s history.

Lastly, Revealers, the next time you go decide to take your coven to afloat, please invite us! Our brooms are ready.

Coven Of Paddle Board Witches Spotted On River

Now, how about some artwork?

Spencer Dew writes about “Almost Like Praying”: The Religious Work of “Hamilton” Creator Lin-Manuel Miranda for Religion Dispatches

Surely the underlying prayer of “Almost Like Praying” is not just for Americans to empty their piggy banks in order to help their brothers and sisters in Puerto Rico, but for this song to prompt American citizens to realize that the catastrophe in Puerto Rico predated the storm, and is, indeed, the result of American policy; policy rooted in imperialism and its corollary racism; policy inconsistent with the basic legal ideals of democracy; and policy the result of which is radical injustice.

We were thrilled to see My God Has Another Name by Kameelah Janan Rasheed up at Triple Canopy

Given my upbringing, when I encounter men on the streets of New York lambasting sinners and promoting gospels, I think of the idiosyncratic religious communities—and lineage of black prophecy—to which they belong and which are obscure to most passersby. In order to address the overall conditions and existential concerns of black people, Ali and his contemporaries called on religion, politics, philosophy, art, music, and costume, among other resources; they alloyed fragments of ideologies, scripture, spiritual maxims, and economic agendas. Now, I wonder, what draws black people to the Moorish Science Temple, and what makes them stay? Can these movements—or whichever nascent movements have yet to impinge on my consciousness and have yet to be named—promise a future that outshines those on offer by the National Baptist Convention or African Methodist Episcopal Church? Can they, at least, provide the satisfaction of self-invention and satisfy the will to write one’s own story?

And, speaking of photography, Errol Morris reviewed Peter Manseau‘s new book for The New York Times Book Review in The Man Who Photographed Ghosts

In “The Apparitionists,” Peter Manseau takes us on an expedition through the beginnings of photography and its deceptions. No sooner had people invented a way of creating photographic images (whether it was a daguerreotype, an ambrotype or a hallotype) than people found ways of altering the images — and, even more relevantly, of lying about their contents and how they were obtained. A photograph, as we well know, can’t talk back. It’s like a piece of taxidermy. It can’t say to us, “No, I’m not a picture of Abraham Lincoln.” And often the provenance of a photograph, its causal connection to the world, is hidden. All we’re left with is an image that, for all intents and purposes, could have been given to us by aliens. This is where Manseau comes in. In a world overcome with death and the horrible losses of the Civil War, people turned to photography hoping to be united with deceased loved ones in perpetuity. It’s that strange combination of desire, hope and the presence of an image that seems almost alive that makes us think we’re in contact with a timeless realm that transcends death.

And you can listen to Leonard Lopate interview Manseau in The Photographer Who Captured Ghosts Peter Manseau on WNYC

Lastly, how about a question to bring to your Thanksgiving dinner: What’s your favorite fictional religion?

Lastly, some enlightened tote bags to take on your holiday travels:

Okay, that’s it. We’re off to the annual American Academy of Religion conference (pictured below) in Boston. Come find us!