Dear Readers,

We have been putting these links roundups together for a while now, and this one has been by far the most daunting yet. This last month, so many people have had so much to process and, thus, have written so much. We have spent the weeks since our last issue swinging between a compulsion to click every headline, read every word, reach for every life raft of critique or insight and just wanting to shut it all down, close the laptop, click the big red circle with the “x” in it, and clear our heads — sometimes selfishly, and sometimes just to get it ready to keep processing, keep getting ready for what’s next. Also, you know, we had some editing to do, some of our own contributions to add. And we had a blog to launch and a new channel to open, but that’s not the point right now. The point is that we always want our “In the News” feature to be useful, and now, we really, really want it to be useful. So this month, we’re not just including articles, lots of brilliant, brilliant articles, but also a couple of guides made by other folks of things to do and advice on how to do them. Because if all this reading has convinced of us of anything, it’s that we have a lot of work to do, it needs to be done right, and reading will always be a big, crucial, part of it. Also, GIFS. We don’t want to be a part of any revolution that doesn’t have GIFs.

Sincerely,

The Editor/ Link Hoarder in Chief/ Most Grateful Servant of Our Lord The Evernote

***

THE ELECTION: WHAT HAPPENED & WHAT NOW?

There are a few clarion voices whose work we especially rely on for clear and incisive thinking. Fortunately, these writers have rallied and shared with us some crucial insights in the last few weeks. Here is a selection of work from them.

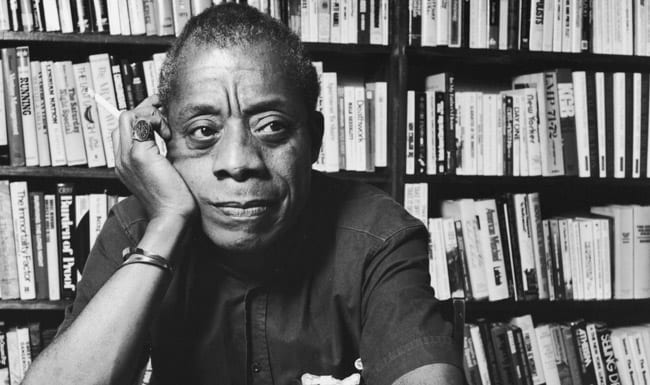

Published just a few days before the election, Scott Korb wrote about Baldwin in the Obama Years for Guernica.

And yet, as I consider teaching Baldwin again this fall—in the wake of a new election—he once again advises, in ways I’ve realized I’d long ignored, against assuming that white Americans are “in possession of some intrinsic value that black people need, or want.” Yet not too long ago, I scratched the name “obama” alongside the very example Baldwin offers of how this assumption “is revealed in all kinds of striking ways,” including “Bobby Kennedy’s assurance that a Negro can become President in forty years.” The same “obama” appears in the margins a few lines above there, as well, alongside this line: “He is the key figure in his country, and the American future is precisely as bright or as dark as his.”

That is a terrible reading, exactly the opposite of what Baldwin says. And it only became clear to me as I taught the book over the past few years—Niebuhr now nowhere to be found—following the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland,Philando Castile, Alton Sterling, as we discussed the protests in Ferguson and the renewed vigor and revolutionary moment captured by Black Lives Matter, that Obama is not the key figure in this country. I had been wrong: the American future is precisely not as bright or as dark as his.

Diane Winston published this valuable statement at Religion Dispatches first thing on the morning of November 9: Might, Right, and White Privilege: It’s Morning in America, The Sequel.

The 2016 election will be sliced and diced for years to come. We will debate whether the outcome was due to sexism, racism, economics, health care, anti-globalization, Clinton’s campaign decisions, anti-incumbency, and a host of other reasons. But let’s not forget the role of religion. And let’s not assume religion, in its evangelical Christian form, is a Sunday-only, simple piety, scripturally unsophisticated business. Conservative evangelicalism, like all other forms of religion, is entwined with all aspects of human existence.

It is unlikely that we are the first in your online world to tell you that Masha Gessen‘s perspective is indispensable. Even if you’ve already read it, though, maybe reread her two recent essays for The New York Review of Books.

Autocracy: Rules for Survival:

Rule #1: Believe the autocrat. He means what he says. Whenever you find yourself thinking, or hear others claiming, that he is exaggerating, that is our innate tendency to reach for a rationalization. This will happen often: humans seem to have evolved to practice denial when confronted publicly with the unacceptable.

And, Trump: The Choice We Face:

Realism is predicated on predictability: it assumes that parties have clear interests and will act rationally to achieve them. This is rarely true anywhere, and it is patently untrue in the case of Trump. He ran a campaign unlike any in memory, has won an election unlike any in memory, and has so far appointed a cabinet unlike any in memory: racists, Islamophobes, and homophobes, many of whom have no experience relevant to their new jobs. Patterns of behavior characteristic of former presidents will not help predict Trump’s behavior. As for his own patterns, inconsistency and unreliability are among his chief characteristics. …

We cannot know what political strategy, if any, can be effective in containing, rather than abetting, the threat that a Trump administration now poses to some of our most fundamental democratic principles. But we can know what is right. What separates Americans in 2016 from Europeans in the 1940s and 1950s is a little bit of historical time but a whole lot of historical knowledge. We know what my great-grandfather did not know: that the people who wanted to keep the people fed ended up compiling lists of their neighbors to be killed. That they had a rationale for doing so. And also, that one of the greatest thinkers of their age judged their actions as harshly as they could be judged.

Similarly, Kelly J. Baker is an expert on an horrifyingly relevant phenomenon, The Ku Klux Klan. Here are three articles in which she shares her critical knowledge:

Nice, decent Folks on her blog Cold Takes:

What I struggled with book after book was the apparent shock that racists could appear nice and decent. Why did these ethnographers not realize that niceness doesn’t equate with anti-racist? Someone can appear nice and still be a bigot. Someone can claim that they are decent and good and still be racist. Nice and decent don’t preclude bigotry. Smiles and small talk are very good at hiding (masking?) it. …

What I realized was how tired I am of hearing how “nice” and “decent” the people are who voted for Trump. I’m so damn tired of this particular excuse because so-called nice and decent white voters put bigotry in office. “Nice” and “decent” don’t necessarily negate racism. Klan members can seem nice and still be racist. And “nice” and “decent” is often only extended by white people to other white people. This is pretty much only a shock to white people.

White-Collar Supremacy in The New York Times:

While it might seem newsworthy that today’s alt-right members wear suits and profess academic-sounding racism, they are an extension of these previous white supremacist movements, dressed up in 21st-century lingo, social media and fashion. We ignore that continuity at our peril: Focusing on their respectability overlooks their racism, but more pressingly, by convincing ourselves that they are taking a new, mainstream turn, it makes white supremacy appear normal and acceptable.

And The Klan Never Ends for Killing the Buddha:

And yet, the reaction to my Klan book suggests to me that white readers often make that mistake again and again. White supremacy is a structure of our lives. The Klan, at least, tends to admit that crucial fact as they fight to maintain it. So, yes, you be upset, angry, or heartbroken that folks are Googling the Klan, but also recognize that white supremacy is not contained in these movements. White supremacy never was. The Klan might seem to end at certain historical moments, but racism doesn’t go away simply because the Klan does. The targets, victims, and survivors of Klan terrorism know this.

Photo by Duardo Munoz/ Reuters)

Likewise, Ajay Singh Chaudhary and Raphaële Chappe went in depth on The Supermanagerial Reich for the Los Angeles Review of Books.

With the global rise of demagogues of the far-right like Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, Viktor Orban, Narendra Modi, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, “fascism” is on the tip of everyone’s tongues. Water-cooler conversations turn around these strongmen or strongmen-in-waiting and their potential to tower over the political landscape of the 21st century. Second- and thirdhand versions of Hannah Arendt and Theodor Adorno have become a welcome addition to the American media landscape. We are all deeply invested in the ideology and psychology of fascism.

Yet, for all this talk of fascism in the air, it’s remarkable how much we have come to accept predominantly ideological and psychological — as opposed to formally political and economic — frames for our arguments. Few people want to talk about how fascist societies like Nazi Germany actually functioned, how they were built, who made them work, and why. But when we do, a much sharper image emerges, in which an idiosyncratic economic and political structure is more clearly visible.

In Nazi Germany, economic history shows us a rapid change in the distribution of income and the emergence of a managerial elite who obtained an outsized share of national income, not just the now-proverbial one percent, but the top 0.1 percent. These were Nazi Germany’s equivalent to today’s so-called “supermanagers” (to use Thomas Piketty’s now famous term). This parallel with today’s neoliberal society calls for a closer examination of the place of supermanagers in both regimes, with illuminating and unsettling implications.

With Chaudhary later going on to articulate What a Proper Response to Trump’s Fascism Demands: A True Ideological Left at Quartz:

Are you thinking: This is not the America I know? We have always been getting better? The Obama years were all grace and beauty? If you are someone who—in earnest—thought about Clinton’s experience in government as anything other than part of all that the immiseration above? Then it is you who are in a bubble. Put down your screeds about rural whites or minority turn out. There is more than one kind of class politics; class does not always mean “working class” and race is also sometimes class. If you were under the strange impression that life has been getting better for the past 40 years, you must understand that neoliberalism—in all its already existing racist glory, with its vicious class warfare against the poor and working class—was working for you. It is your class politics; it is your race politics. And those politics—barely sputtering through the Obama years—have finally crashed. …

Every liberal commentator and political actor must understand that even the slightest inch given to Trump helps legitimize and normalize not only him but the acts that will come in his name, just as their feckless collaboration with George W. Bush in the Iraq War and Obama’s drone campaigns and deportations made those gross crimes part of “acceptable” everyday life. Instead, even ideologically committed liberals should hope for something that they can barely seem to stomach: a true Left. The time is now.

And Katherine Franke takes up the work of critiquing liberals and liberalism in her scorchingly on point rebuttal to Mark Lilla, Making White Supremacy Respectable. Again, for the Los Angeles Review of Books Blog:

Let me be blunt: this kind of liberalism is a liberalism of white supremacy. It is a liberalism that regards the efforts of people of color and women to call out forms of power that sustain white supremacy and patriarchy as a distraction. It is a liberalism that figures the lives and interests of white men as the neutral, unmarked terrain around which a politics of “common interest” can and should be built. And it is a liberalism that regards the protests of people of color and women as a complaint or a feeling, ignoring the facts upon which those protests are based — facts about real dead, tortured, raped, and starved bodies. The liberalism Lilla espouses reduces these facts of human suffering and the systems of power that produce that suffering as beside the point. What matters are liberal values and the idea of America as a “shining city on a hill” that deserves our allegiance, not our protest. The ways that racial inequality has been baked into liberalism through the structural disadvantage of black people found in the GI Bill, discriminatory lending policies, redlining, inferior education for people of color, and — oh right — the refusal to provide reparations to formerly enslaved people, are just glitches and not actual features of the splendors of liberal governance for the likes of Lilla.

And they don’t come any sharper or smarter than Kathryn Lofton who wrote:

Trumping Reality for The Immanent Frame:

Power is a discourse, and Trump wields it like the boss of bosses, like the infant Jesus, like you if you get to be unhinged from the rules of engagement. In the wake of Trump’s candidacy, we could do better in examining accounts of this unhinged authority—however fantastical, however absurd—to understand the story of his ascent rather than to obsess about supporters’ self-delusion. We might also reflect on the strange circulation of strange ideas. If the history of religions teaches us anything, it is that a dose of absurdity does nothing to diminish the potency of a call to power. If anything, it is the missing ingredient, the yeast of effervescence.

And Understanding is Dangerous for The Point Mag:

To be a scholar of religion is to participate in a hermeneutics of the incomprehensible. That isn’t exactly right: what scholars of religion do is account for why groups of people consistently agree to things that other people think are incomprehensible, irrational, even senseless. Images illegible relative to contemporary notions of geometry or perspective; abstractions so abstract they twist the brain; doctrines so specific they seem impracticable; myths so fantastic they seem extraterrestrial. Through documentary engagement, linguistic specificity, historical and sociological and economic analysis—scholars of religion make those things legible as human products of human need.

It is therefore unsurprising that I, a scholar of religion, am invested in an account of Trump that renders his absurdity less so.

Image via The Washington Post

We also wanted to share two critiques from within the world of religious studies. The American Academy of Religion, the main scholarly association for academics of religion in the humanities, met last month for its annual meeting. The Revealer was there, hosting a panel on Writing Religion Online (video forthcoming). The theme this year was “Revolutionary Love.” Two scholars we respect published responses to the conference in the Bulletin of the Study of Religion (which had hosted a year-long forum on the theme, all of which is worth checking out).

Revolutionary Love, and the Colonization of a Critical Voice: An Outsider’s Reflections by Laura Levitt:

If this is radical love, I want no part. Here in the words of this most compelling social critic [Michelle Alexander], I no longer felt welcome. The universal proclamation of this session and its revolutionary love had no place for Jews or Muslims, for Hindus or Buddhists, and certainly not for the many atheists and agnostics of any and all stripes who are part of this scholarly organization. In our bounded differences from these well-meaning and progressive Christians, we were, it seems no longer welcome.

And, Why I was scared to attend the AAR this year by Hussein Rashid:

The AAR’s theme this year is belied by their actions. There is no love. There is not empathy. There is no compassion. It may not be the academic way, and I am happy to say that I am doing academia wrong. I believe in a mission of the humanities that allows students to see the worth in themselves and in other people; to be curious and to explore. When I hear from students from the various institutions I have taught at that they want to talk about the recent election of Donald Trump, but none of their faculty are talking about it, I believe they have been failed. What they are being taught does not match up with their experiences.

We also appreciated this all too relevant Public Statement from the Society for Classical Studies Board of Directors:

The mission of the Society for Classical Studies is “to advance knowledge, understanding, and appreciation of the ancient Greek and Roman world and its enduring value.” That world was a complex place, with a vast diversity of peoples, languages, religions, and cultures spread over three continents, as full of contention and difference as our world is today. Greek and Roman culture was shared and shaped for their own purposes by people living from India to Britain and from Germany to Ethiopia. Its medieval and modern influence is wider still. Classical Studies today belongs to all of humanity.

For this reason, the Society strongly supports efforts to include all groups among those who study and teach the ancient world, and to encourage understanding of antiquity by all. It vigorously and unequivocally opposes any attempt to distort the diverse realities of the Greek and Roman world by enlisting the Classics in the service of ideologies of exclusion, whether based on race, color, national origin, gender, or any other criterion. As scholars and teachers, we condemn the use of the texts, ideals, and images of the Greek and Roman world to promote racism or a view of the Classical world as the unique inheritance of a falsely-imagined and narrowly-conceived western civilization.

And, because truly no one is immune from Godwin’s law, we should all read this clipping that BoingBoing dug up, Hitler’s Only Kidding About the Jews:

“Several reliable, well-informed sources confirmed the idea that Hitler’s anti-Semitism was not so genuine or violent as it sounded, and that he was merely using anti-Semitic propaganda as a bait to catch masses of followers and keep them aroused, enthusiastic, and in line for the time when his organization is perfected and sufficiently powerful to be employed effectively for political purposes.”

“You can’t expect the masses to understand or appreciate your finer real aims. You must feed the masses with cruder morsels and ideas like anti-Semitism. It would be politically all wrong to tell them the truth about where you really are leading them.”

But please do read it along side Dania Rajendra‘s important call in: Max Goldberg’s “Would you Hide Me?” Gets it Wrong at Jewschool.

This a moment where we, as Jews, must harness our legitimate concern to do better, in public and in private, than gatekeeping new friends. It is both a moral and practical imperative that we open ourselves, our communities, our lives to our non-Jewish friends and family.

Lastly, our good religion-publication-editor-friend Brook Wilensky-Lanford wrote a list we probably all dream of writing and enforcing in her piece, Election History, Second Draft, at Killing the Buddha:

When I was in seventh grade, my English teacher forbade us from using the words “very” and “interesting” because they were meaningless, and worse–because they took up space that could be used actually trying to explain the thing in question. In that spirit, I humbly offer a list of words and phrases that I would like to see eliminated from the election story in favor of more evocative constructions.

Want more lists in your list? Great! Keep reading.

FORUMS

Not done yet? Good. There’s a lot more, The New Yorker (Aftermath: Sixteen Writers on Trump’s America), n+1 (The Election: Responses to the 2016 presidential election), and The Boston Review (Trump Says Go Back, We Say Go Forward) each published forums on the aftermath of the Election. We recommend all of them.

RESOURCES

Okay, now you’re really probably done reading about the election. (Thank you for sticking it out. We promise, there are memes at the end!) Here are a few action guides we thought were especially useful. We’d love to hear about others if you have any to recommend.

A Time for Treason a reading list compiled by the editors of The New Inquiry.

The Trump Syllabus 2.0 at Public Books

The Oh Crap! What now? Survival Guide an epically extensive collaborative effort

Wall of Us which offers “four concrete acts of resistance delivered to your inbox each week”

And hollaback! has created a very useful and important collection of Bystander Resources

NON-ELECTION RELATED

Much as there is happening here, it’s probably a good idea to check in some other places every once in a while, because, for instance, this is happening: China Takes a Chain Saw to a Center of Tibetan Buddhism by Edward Wong for The New York Times.

The chain saw, wielded by workers demolishing a row of homes, signaled the imminent end of thousands of hand-built monastic dwellings here at Larung Gar, the world’s largest Buddhist institute.

Since its founding in 1980, Larung Gar has grown into an extraordinary and surreal sprawl — countless red-painted dwellings surrounding temples, stupas and large prayer wheels. The homes are spread over the walls of this remote Tibetan valley like strawberry jam slathered on a scone.

Larung Gar has become one of the most influential institutions in the Tibetan world, the teachings of its senior monks praised, debated and proselytized from here to the Himalayas. In recent years, disciples have popularized a “10 new virtues” movement based on Buddhist beliefs, spreading its message across the region.

A Buddhist nun with a prayer wheel in Larung Gar, a monastic camp where thousands of nuns and monks live and study, in Sichuan Province, China. Credit Gilles Sabrié for The New York Times

A good bit closer to home, Kiera Feldman did some remarkable reporting for Harper’s, With Child: The right to choose in Rapid City.

“Getting doctors is the number-one problem everywhere,” Alexander Sanger, the president of Planned Parenthood of New York City, told the New York Times in 1992. The restrictive laws that have swept the country since then have exacerbated long-standing issues of access. Today, many secular hospitals are merging with tax-exempt religiously affiliated facilities, many of which refuse to do abortions even in cases of nonviable fetuses. In a Catholic hospital, the termination of a fetus without a brain, for example, is still deemed an elective procedure.

The Black Hills clinic is across the street from a soaring Catholic cathedral, where churchgoers reportedly were once urged to boycott the practice because Marvin Buehner had voiced opposition to South Dakota’s attempts to ban abortion. No one in the building performs elective abortions, yet protesters still visit, carrying signs that proclaim real doctors don’t kill babies. Buehner explained that adding surgical or medication abortion to the clinic’s list of services would make it difficult to provide any other services and possibly jeopardize the practice. Women seeking a Pap smear or an IUD insertion don’t want to have to brave throngs of screaming protesters.

Another local ob-gyn said that the mere fact that she was pro-choice would be enough to prevent other doctors, if they knew, from referring patients to her.

And, right here at home in Manhattan, Whores and Hell Beasts: An Earth-Shaking Treatise Is in New York.

New Yorkers can choose from dozens of cultural institutions when they want to lay their eyes on exquisite antiquities and masterworks of art. But a case could be made that, right now, a single sheet of paper in a room on Madison Avenue is the most compelling object in the city.

The room is at The Morgan Library and Museum. It is host to an exhibition with the lackluster title, “Word and Image: Martin Luther’s Reformation.” But the artifacts and manuscripts are sublime, especially those that illuminate the lengthy print war between the German monk and Pope Leo X. Each party commissioned artists to portray the other as a whore or hell beast, the smear of choice among Christian believers in the years after 1517, when Luther first publicly charged the Pope and the Vatican with corruption.

Meanwhile, Ann Neumann and James Sprankle traveled to Pennsylvania to report on Faith and Its Limits for The Virginia Quarterly Review.

Amish and many Mennonites don’t have insurance. It’s theological; when your history, your belief, is shaped by a marauding government that slaughtered—martyred—your ancestors, chasing your founders across the ocean on ships (what are ships to farmers?), you foster separateness. You know there are no absolutes; you vote sometimes, you avoid the military, you pay some taxes. Still, you’d prefer to take care of your own.

Photo by James Sprankle for the Virginia Quarterly Review

Something we definitely need to talk about: Can Television Be Fair to Muslims? by Melena Ryzik for The New York Times

Less than two weeks after Election Day, five showrunners gathered in New York to discuss the representation of Muslims on TV. Howard Gordon, the showrunner and executive producer of “24” and “Homeland,” has faced these issues the longest; after “24” emerged as a lightning rod for its stereotyped depictions, he engaged with Islamic community groups to broaden his understanding. (Mr. Gordon is an executive producer of the rebooted “24: Legacy,” debuting in February.) Joshua Safran is the creator of “Quantico,” an ABC series about F.B.I. operatives.

Aasif Mandvi, an actor and former correspondent for “The Daily Show,” is adapting his comedy “Halal in the Family” for an animated series. Zarqa Nawaz is the creator of the Canadian series “Little Mosque on the Prairie” (available on Hulu). Cherien Dabis, a filmmaker known for her 2009 indie “Amreeka,” about a Palestinian single mother who emigrates to the United States, was a writer on “Quantico” and now works on “Empire.” She took part via FaceTime from Los Angeles.

The conversation was thoughtful, anxious and determined. All seemed well aware of the stakes. “It’s really popular culture that impacts how people feel about one other,” said Sue Obeidi, the director of the Hollywood bureau of the Muslim Public Affairs Council, which works with networks and studios to promote Islamic voices.

Also urgent: The refugee crisis and religion: Beyond physical and conceptual boundaries edited by Erin K. Wilson and Luca Mavelli at The Immanent Frame.

What seems to have been forgotten in the dominant narratives around the refugee crisis is that, to put it simply, refugees are people. Commentaries that overly emphasize religious identity or focus predominantly on whether someone is a “genuine refugee” or an economic migrant—a distinction that is largely meaningless on the ground—willingly or unwillingly neglect the complexities that make up human beings who are currently displaced. They are not just Muslims or refugees—they are parents, children, brothers and sisters, doctors, lawyers, teachers, engineers, citizens, activists, friends. Their identities are complex and cannot be reduced to simplified categories of Muslim or refugee.

Scholars and public intellectuals must continue to stress the diverse nature of Islam, de-link Muslim, refugee, and terrorist in broader public consciousness, and remind people of the humanity of those who are currently displaced. And, we must push our politicians, policymakers, and media to do the same. We must contribute to the creation of safe spaces for difficult conversations and encounters with “others.” Most crucially, we must ensure that the advice and experiences of refugees themselves is a central component of these public conversations. Shifting focus from religious identity to solidarity with fellow human beings whose survival is at stake would be a significant step in shifting dominant discourses and attitudes to the crisis, generating greater space for alternative political and societal responses.

And we’d be remiss if we didn’t tell you that The Baffler has a beautiful bunch of religion writing for you in its thirty-second issue, Muzak of the Spheres:

Rare it is that the careworn American public casts its collective gaze heavenward—unless in desperate prayer for debt relief, affordable housing, non-extortionate college instruction, or any of the other fugitive comforts that our grand neoliberal consensus has catapulted into the unreachable empyrean. In the hushed and reverent darkness of the Baffler observatory, however, we hew closely to the counsel of that great socialist bon vivant Oscar Wilde: “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

Lastly, seriously, Leonard Cohen’s death was just the absolute last thing we needed this year. At least we have these perfect eulogies.

My Friend Leonard Cohen: Darkness and Praise by Leon Wieseltier for The New York Times:

Eliezer was his Hebrew name. We sometimes read and studied together, Lorca and midrash and Eluard and Buddhist scriptures and Cavafy. We could get quite Talmudic, especially with wine. In Judaism there is a custom to honor the dead by pondering a text in their memory. Here, in memory of Eliezer ben Nisan ha’Cohen, is a passage on frivolity by a great rabbi in Prague at the end of the 16th century. “Man was born for toil, since his perfection is always being actualized but is never actual,” he observed in an essay on frivolity. “And insofar as he attains perfection, something is missing in him.

Traveling Light: Farewell to Leonard Cohen by Anahid Nersessian in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

I grew up in a secular household, but my family had two saints: Freud and Leonard Cohen. Both my parents are psychoanalysts, so we believed in self-scrutiny, the diagnostic power of dreams, and that nothing is more universal than perversion. To explain the almost scriptural role Leonard Cohen’s songs played and still play for me, I have to say something about New York City in the 1980s, as it sounded to a girl with orange-yellow skin and, in that pre-Kardashian era, an unintelligible name.

COMIC RELIEF

You made it! We thank you for your faith, even if it is faithless, like these Atheist Shoes, which are a real thing:

And we’re not done laughing at Joe Biden and Barack Obama Memes:

***

-Kali Handelman, Editor, The Revealer

***

You can find previous “In the News” round-ups here.