By Don Jolly

Salem Kirban, the author of 666, was forty-two when he flew to Vietnam. It was 1967. His son, Dennis, had enlisted the previous fall, and within six-months he’d been posted to the coastal city of Nha Trang. Back home, the war was everywhere: on television, in the paper, shaped in rough paint on picket signs. Again and again, Salem saw the human cost of war reduced to numbers: “body counts.” He was worried that Dennis might be killed, but he was equally worried that Dennis might be forced to kill someone else.

The Kirbans were a “fundamentalist” family. Salem, his wife Mary and their five children attended services at the evangelical Church of the Open Door, in a suburb of Philadelphia. Salem sang in the choir. He wasn’t sure why the United States was in Vietnam: the official story didn’t make sense to him and he wasn’t sure if the domino theory was true or just propaganda. It seemed grotesque to murder someone for no reason at all when the word of God in Exodus 20:13 was clear: “Thou shalt not kill.” In a letter to Dennis, his mother wrote: “shoot to wound.” It became a family issue. They talked it over at the dinner table.

About a week ago, I spoke to the oldest of Kirban’s daughters, Doreen, by telephone. She was around fifteen when Dennis shipped out, but now she’s near retirement age. Her voice was bright and boisterous. Even though they went to Church, she said, her family didn’t have much of a religious identity while she was growing up. Church was just what you did, a part of the routine. “Dad was into advertising, making money,” she continued. Things began to change in 1966. “Dad served in World War Two,” Doreen explained. “So he wasn’t big into war. Vietnam bothered him. It became personal when Dennis went over. That’s when he took out the ad.”

On July 12th, 1967, a fourteen-inch advertisement appeared on an interior page in the Washington Post. Its title, “GOODBYE MR. PRESIDENT,” was printed at the top of the box in bold letters. Below it, in eight-point font, Salem Kirban explained that his son was in Vietnam and he didn’t know why, exactly. He’d asked for a private meeting with Lyndon Johnson, a chance to explain things, but had been turned down. “So I decided to do the next best thing,” Salem wrote. “Fly to Viet Nam, Israel, Egypt, Jordan and Russia and prepare a Citizen’s Report on the Search for Peace.” He invited Johnson to see him off at Philadelphia International Airport in four days. The President never appeared.

Kirban visited Japan, Vietnam, Lebanon, Jordan and Israel on his tour, returning in mid-August. He met with a Japanese progressive journalist with ties to the Vietnamese communist party, attended a briefing from General Westmoreland and traveled all around war-torn Vietnam, talking to soldiers and priests and mortuary attendants. His happiest days, however, were spent in Nha Trang, with Dennis.

Upon his return, he wrote a book on the subject. Goodbye Mr. President was published before the end of the year, by a private press. In it, Kirban argued that the official stories about Vietnam were lies; conditions there were worse than anybody let on. Responses to the war were also a problem. “It’s easy to be a protest marcher or a mere flag waver spouting patriotism,” he wrote. Neither addressed the fundamental issue. “Many people seem to forget first that America was a nation founded under God,” continued Kirban. “This neglect may be at the root of all our rapidly multiplying problems.”

In 1968, Kirban wrote his second book: Guide To Survival (which you can read about here in last month’s column). In it, he repurposed many of the photographs and first-hand reports employed in Goodbye Mr. President. This time, however, he saw a pattern running through them all. The children ravaged by napalm, the refugees in rags, the wall of aluminum caskets sitting matter-of-factly on a Saigon airfield — all had been foretold in the book of Revelation. It was evidence that the current age, or dispensation, of biblical time was ending. Soon, Kirban predicted, the last few faithful Christians would disappear in the Rapture. After that, the faithless churches that remained would join together into a one-world religion. There would be global government, too: a dictatorship, with the Anti-Christ at its head.

“Dad didn’t get into God until he saw those caskets,” said Doreen. “But once he got going with the whole thing, he thought he needed to wake people up.” Salem started traveling to speak about biblical prophecy in churches and rented conference rooms. His books, which he sold by mail-order, did respectable business.

“When he wrote the novel, I was shocked,” Doreen told me, a note of amazement intruding on her tone. “I didn’t think he had it in him.”

The novel, 666, was released in 1970. In it, Salem rendered his interpretation of current events and biblical prophecy through a globe-spanning adventure story, set in the not-too-distant future. Initially, the protagonist, a journalist named George Omega, has little use for Kirban’s brand of “fundamentalism.” After his wife vanishes in the Rapture, though, he begins to reconsider. As the reign of the Anti-Christ wears on, and conditions grow more dangerous and bizarre, Omega, along with two of his children, is born again.

“This book — 666 — is a novel. Therefor, much of it is fiction,” Kirban wrote. “However, it is important to note that very much of it is also FACT.”

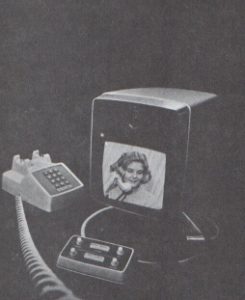

He continued: “Using the scripture as our basis… it is a fact that there will be Rapture… It is a fact that after this occurrence there will be at least a seven year period of great trials and tribulation.” The science-fictional technology of 666 was also based on truth, he said. “Such items as the picturephone, the ruby laser and the flying belt … already exist, although they have not always been perfected to the point we relate them in our novel”

The book begins with eleven pages of newspaper clippings that support its author’s claims. A selection of those headlines:

Army Orders Witnesses Not to Discuss Massacre

Newsmen Receive Vatican Warning

Monkey Brains Kept Alive Outside Skull

Kirban’s youngest daughter, Dawn, was around eleven when 666 was issued. Like Doreen I caught her on the phone. In some ways, she remembered her father differently from her sister. Faith was a bigger part of her life. After dinner, she said, Salem would read to the family from the Bible and talk about current events. He spent a lot of time working, putting together projects about the end-times. “Dad wrote the words to a cantata,” she recalled. “A big, hour-long show called ‘The Day of Judgment.’ There was an album and everything, and we put it on with the choir at church.” She remembered having to be quiet when he was doing research for his Reference Bible, a new edition of the text with full commentary by Kirban and his friend Gary G. Cohen. The Rapture was taken for granted in their household. “I never expected to grow up,” she said.

“I remember, I used to have a recurring nightmare,” Dawn continued. “I had to choose if I would take the mark of the Anti-Christ, 666, or get my head cut off. I’d be lead over the guillotine and there were all these men, pushing me around, and they’d shove my head in the little hole and I was so scared — but I wouldn’t do it, I wouldn’t take the mark, and so they’d get ready to kill me. Then I’d wake up.” She paused. “It was all right out of dad’s book.”

In 666, the Anti-Christ reinstates the guillotine as a punishment for those who refuse to be tattooed with his number, a literary construct built out of Kirban’s interpretation of Revelation 13, in which it is stated that the Beast “causeth all, both great and small … to receive a mark in their right hand, or in their foreheads,” allowing them to “buy and sell.” Bill Sanders, one of the novel’s main characters, refuses to take the mark, and is executed in public. As Bill walks up the steps to the guillotine, looking out at the mob of Americans calling for his head, he reflects about the state of the world. “It seemed like bad dream … a nightmare,” Kirban wrote. “Down there, wherever he looked … upturned faces, sneering, scoffing, all bearing the brilliant red 666 on their foreheads. ‘What happened to humanity?’ [Bill] thought. ‘Have they all turned into a pack of wild animals?’”

The logic of Kirban’s story is, deliberately, the logic of a dream. Its reality is fluid: a whorl of surprise remembrances and snap alternations of setting and character. At one point, Kirban’s protagonist suddenly remembers, sixty-six pages into the story, that he has an adult daughter living in New York City. At another, he travels to the moon for the span of a few sentences. The effect is disorienting.

As in any fitful sleep, 666 is suffused with elements from more conventional reality, presented in disguise or in random order. The newspaper clippings at the start of the book are all accounted for: even the monkey brains make sense, once the Anti-Christ is shot and his scientists have to remove his brain to keep him alive.

The biggest influence on 666, however, is Kirban’s interpretation of biblical prophecy. Almost every element of the novel’s plot can be traced to a specific reading of a passage from Ezekiel or Revelation. Kirban’s interpretation of Revelation 6, for instance, was fairly literal. To him, the four horsemen of the apocalypse must, naturally, ride horses. So, in 666, the author has to explain why a modern army would do the same thing, forgoing tanks and jeeps and helicopters. Kirban solves this problem with the character of Alexi Bazenoff, the Soviet Premier. Bazenoff, Kirban explains, was the grandson of a biblical scholar named Pop Pop Koschenov, and Koschenov raised him on passages from Ezekiel and Job about the power of the horse as a weapon of war. So, when the grown-up Bazenoff invades Israel, he does it on a red horse, just like in Revelation. It fits Kirban’s prophetic scheme, of course, but it does something else, too: by giving so much thought to Alexi’s motivation, the author makes this little corner of his apocalypse more about a boy trying to live up to his grandfather’s expectations than any kind of divine machinery. It’s surreal — but sweet, too.

Kirban’s approach to interpreting prophecy wasn’t original. He picked it up, like most American evangelicals, from more than century of writing and preaching about dispensational premillennialism, a theology of history that contained the Rapture and the idea of apocalypse arriving at time of God’s choosing, no matter what humankind got up to. He wasn’t the first one to write a novel about these ideas, either, although 666 easily outsold its predecessors. Evangelicals were breaking into American pop-culture in a major way at the beginning of the seventies. In the same year as Kirban published 666, the authors Hal Lindsey and Carole C. Carlson put out The Late, Great Planet Earth: an accessible book of end-times prophecy that would go on to sell more copies than any other non-fiction book of its decade. “Kirban’s 666 sold half a million copies in its first three years, and, for a time, its sales must have been almost as impressive as those of Lindsey’s market-defining text,” wrote the historian Crawford Gribben in his 2009 survey Writing the Rapture: Prophecy Fiction in Evangelical America. “The large sales of 666 — unprecedented in the genre [of prophecy fiction],” he continued, “indicated the extent to which the prophecy novel was becoming a key component of fundamentalism’s [pop-culture.]”

Later books would be even more successful. The sixteen-volume Left Behind series by evangelical minister Tim LaHaye and popular author Jerry B. Jenkins has sold more than 63 million copies since its first book was released in 1995. A new film adaptation is due this October, starring Nicholas Cage. A lot has been written about Left Behind, and scholars seem to agree that it’s one of the most significant cultural products to come out of American evangelicalism in the twentieth century. Could it have happened without Kirban? Who knows.

At the end of 666, the main characters have to go into hiding from the Anti-Christ, so they fly to Vietnam, and hole up in an old V.C. bunker south of Saigon, at Xuan-Loc. There, Kirban writes, “besides the small supply of man-made provisions they’d managed to collect, they had brought only one thing with them… their Bible.” Until Satan discovers them, his characters spend their days singing. To me, the sequence seems to be the closing of some strange, and personal, circuit. Whatever meaning 666 might have in evangelical pop-culture is just a shadow of the meaning that it held for its author, and his family, in one of the strangest times of America’s last century.

After 666, Kirban kept writing.

“Dad had a listening heart,” Dawn told me. “He related to people, had a lot of hobbies. He was always doing something, always trying something out. He was a gardener, he played baseball in the street. He was interested.”

I asked Doreen about her father’s later life. “He was gung-ho for years,” she said. “He was speaking at churches, writing newsletters. In 2003, he took a trip around the country.” She paused. Then, somberly: “That same year, mom started to go downhill. The year she broke she her hip. The more she lost her memory, the worse he got. He was very attentive to her. He died in 2010, when he was in his eighties.” He’d written more than fifty books. His children are married now, with children of their own.

When I open my paper in the morning, I see American soldiers overseas for reasons I’ve given up understanding. I see messianic predictions about new technologies, and the ways in which they will cure and strengthen and extend us. Over coffee, I read about famine and war.

The world persists, regardless.

***

This article would have been impossible without the participation of Dennis Kirban, Dawn Adkins, and Doreen Frick. Many thanks to everyone in the Kirban family.

***

“The Last Twentieth Century Book Club” is a monthly column about religious ephemera. Prior columns can be read here:

Guide to Survival (Salem Kirban, Part 1)

***

Don Jolly is a Texan visual artist, writer, and academic. He is currently pursuing his master’s degree in religion at NYU, with a focus on esotericism, fringe movements, and the occult. His comic strip, The Weird Observer, runs weekly in the Ampersand Review. He is also a staff writer for Obscure Sound, where he reviews pop records. Don lives alone with the Great Fear, in New York City.