By Nathan Schradle

The Revisionaries, a documentary filmed throughout the course of the 2009-2010 Texas State Board of Education hearings on high school curriculum revisions, saw its American debut at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival and is on the festival circuit this year. I went in fully expecting to be horrified by director Scott Thurman’s portrayal, having spent three years working as a Special Education teacher in public school classrooms, including two in the Vallejo City Unified School District. The district had been subject to intense monitoring and mandatory curriculum guidance by the California State Board of Education due to poor performance on state tests (a system developed as the direct result of another Texas lawmaker’s policy, George W. Bush’s “No Child Left Behind” program). During that time, it was obvious to me that the textbooks were both almost impossible for the students I was working with to relate to and almost entirely whitewashed. From neutered versions of “the Most Dangerous Game” and even “the Odyssey”(don’t expose the children to violence!), it was clear that there was more at stake in what went into the textbooks than a simple assessment of what literature or concepts students needed to learn. In one of my co-taught classes, we made the decision to skip the textbook’s explanation of evolution because it was nonsensical and overly complicated.

Hovering behind this frustration was my fellow teachers’ common assumption that, in spite of the words “California Edition,” emblazoned along the top of each book, the content of the textbooks had actually been decided in settings far removed from the one in which we taught. Teachers didn’t feel enabled by the textbooks—we felt hamstrung. So I came to “The Revisionaries” with certain expectations. I expected it to give me a deeper and better-informed loathing of the way that the Texas State Board of Education (SBOE) has managed to overhaul high school curricula to conform to the standards of a particular brand of hard-line Creationism and political conservatism shared by a small fraction of the population, even in traditionally conservative Texas. It is a testament to the film’s quality and the filmmakers’ perceptiveness that it gave me my anticipated dose of horror, but not at all in the way I’d expected.

To explain exactly how Thurman and his team accomplished this, it is best to look at what Thurman, in a Q & A after the screening, described as the main purpose of the project. “This story has received a lot of media coverage, both good and bad,” he said, “but what hasn’t been shown is that these are real people making these decisions. I wanted to make a film about getting to know the characters involved in the story.” While this isn’t revolutionary docu-speak, this one statement neatly sums up exactly what the film does well, and exactly what I left the theater thinking about: the people, both those on the SBOE and those representing more liberal, dissenting interests throughout the proceedings. It is fair to say that the film had a “main character” as well: Don McLeroy, president of the SBOE during the proceedings regarding the science standards and active member during the deliberations over the social studies curriculum.

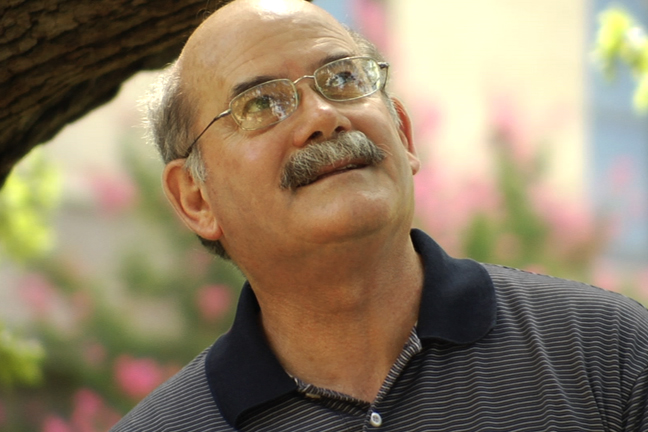

What makes McLeroy so compelling is that even while he presides over some of the most jaw-dropping distortions of scientific and historical fact (he states repeatedly that he knows the Earth is only 6,000 years old, that dinosaurs were on Noah’s Ark, and that this is what every child should learn in school) he seems, plain and simple, like one of the most genuinely kind, friendly people on the planet. In scenes following him in daily life, Thurman’s camera paints a picture of a balding, bespectacled local dentist. He seems down-to-earth. He makes his patients laugh. He carries himself with an infectious affability. Not even the attack ads taken out on liberal radio stations following the vote on the science standards, which cast him as a religious nut in the moral minority with no place in Texas politics, provoke him to lash out. He just smiles, picks up the phone, and calls his friends to say, “do you hear what they’re saying about me?”

Film still from "The Revisionaries": Don McLeroy, Texas State Board of Education member. Source: Scott Thurman/The Revisionaries.

McLeroy’s nature is best exemplified in a scene where he’s teaching Sunday school. He announces to the room full of elementary-aged children that the “secular humanists” are, at this very moment, trying to fill peoples’ heads with the idea that there is no truth, no God, and that we “just evolved.” He goes so far as to say that these secular humanist principles are “contrary to those on which the country was founded.” Then, he takes the entire group out into the sunshine and has them name every species of animal they can think that would have been on Noah’s Ark. The only thing is, he names more species than the kids do, and his ear-to-ear grin seems to suggest he might be having more fun than anyone else involved.

Of course, the film also showcases plenty of unproblematically easy targets for a healthy liberal ire. One, Cynthia Dunbar (who until recently held both a professorship in law at the Jerry Falwell-founded Liberty University in Virginia and a seat on the Texas SBOE), is particularly easy to revile. Watching her prevaricate instead of answering well-intentioned questions, then turn around and make under-the-table deals to force her initiatives through, is a lesson in brazenly corrupt conservative politics. Outside of the council chamber, Dunbar is clear that religion is one of the cornerstones, if not the very foundation, of our educational system. Inside, she rarely mentions religion, instead turning to the well-worn assertion that “evolution is just a theory,” which she attributes to the “scientific experts,” ignoring those very experts’ impassioned pleas to the council regarding the difference between scientific theories and the idea of “theory” in its common usage. Her deployment of these rhetorical elisions almost always leaves the liberal camp both dumbfounded and grasping at straws. During an unrelated prayer rally, Dunbar announces that “truth isn’t a thing, it’s a person,” and calls for Jesus to “invade our schools, homes, and country.” Not the most effective way to make friends who believe in a healthy separation of church and state, but the point is that Dunbar and company don’t care, and don’t need, to consider that type of politesse. And for every moment when Dunbar and her ilk rise to the fore, there is another McLeroy scene lurking right around the corner, ready to charm you with an infectious smile and what every viewer can tell is a firm handshake.

Thus, Dunbar and McLeroy are shown to employ particularly frustrating political strategies that serve to obscure the actual subject of debate. Into the middle of this obfuscation, McLeroy injects a little of his charisma, and most of the board happily falls in line, even as they–sometimes knowingly–have almost no grasp of what they are agreeing to. In this fashion, the conservative bloc on the board moves down the list of items on the agenda, winning victory after victory one standard at a time. As the film progresses, it starts to feel inevitable – McLeroy is always just one more friendly conversation away from another deceptive revision of history. The ire his actions provoke from the more liberal voices participating in the hearings seems destined to fall on deaf ears. Their anger and frustration are no match for his cheery, good-natured efficiency.

Fittingly, the liberal foils to the conservative characters are not nearly so charming. What is most apparent from the get-go is their need to explain the events taking place to the viewer, to make sure that anyone watching later will understand what a travesty is taking place. The most active of them is Dr. Ron Wetherington, an anthropologist (expert in human evolution, not so incidentally) who is called as an expert witness during the hearings. Ron’s incredulity at the outrageousness of the standards being put into law by the SBOE mirrors that of all the liberal voices throughout the film. Ron and the other dissenters come across as more than a little fatalistic – his incredulity is reserved not only for the present moment and the current “bone-headed” decisions (his word, not mine), but the litany of those to come, as well. To hear him tell it, the travesties conceived in the revisions of the social studies standards were the logical conclusion to a tale begun with the science standards and the abuse of the theory of evolution. And to be fair, he may be right.

Opponents of proposed SBOE curriculum revisions demonstration to "Stand Up for Science." Source: Texas Freedom Network.

It really is pretty stomach churning to watch as some of their decisions unfold. The board votes down a proposal to ensure that the concept of institutional racism is taught in government classes. They also make sure to highlight the importance of teaching the superiority of the “Free Enterprise System” over that of “Communist Command.” McLeroy himself cuts several civil- and union rights leaders out of a standard on important individuals in American History to make way for Phyllis Schlafly—yes, that Phyllis Schlafly—presenting no argument, but simply introducing a motion and waiting for it to pass. In perhaps the most amusing of these decisions, McLeroy asks that “Hip-Hop” be replaced with “Country Western music” in a standard describing the significance of the arts in the formation of American culture.

Adding to the discomfort of watching McLeroy, he seems blithely unconcerned with the consequences of his decisions. While what he sees himself as doing is rewriting the way history will be taught in Texas, he is actually, as the film demonstrates, rewriting the way it will be taught nationwide. Textbook editors appear throughout the film describing the way the Texas Standards, being the most censorious and representing the second-largest textbook market in the nation, define the way that textbook companies drafting their curricula. For all but the most politically conservative audiences outside of Texas, the news is not good. Essentially, textbooks are written to appease lawmakers in Texas, and only slightly modified for distribution in other markets in the nation. What is written for Texas ultimately becomes what is available to California, and to New York. So, while McLeroy’s claims about the relative historical importance of Cesar Chavez and Phyllis Schlafly, or hip-hop and country western, evidence a discomfiting position on the relationship between race and American culture, they become even more upsetting when one understands that those claims are on their way to nationwide enshrinement as historical fact.

Yet, despite the shocking ease with which he twists fact to conform to his own notion of truth, I couldn’t help but like McLeroy. His appeal is undeniable. He says what he means, and he does what he says. The sincerity of his belief leads to an authenticity of action that is hard to fault, even if the actions carried out may seem unconscionable from a different point of view.

What’s more, McLeroy is the shining example of one of the film’s most interesting undertones. Even as the liberal camp laments its position and watches it interests crumble in the face of a superior (better organized, more unified) political front, McLeroy also experiences some hard times. Between the hearings on the science and the social studies standards, he’s voted out as President of the SBOE. The last scene of the movie shows McLeroy walking with a long-time friend and discussing the election. He says that there was something serendipitous about his loss, since, by stripping him of his administrative authority but giving him the right to introduce his own motions to the panel, the demotion allowed him “to do so much good work with the social studies standards.” Not only does he use religious language to describe the situation, he also attributes his ability to rebound from his “little setback” to his faith. It’s as if, in Don’s mind, there’s no way he can lose. Unfortunately, the film narrative seems to speak the same truth. In the end, “The Revisionaries” raises a troubling possibility: the cure for the near-fatalism that has plagued the liberals throughout the SBOE process is, to hear McLeroy and Dunbar tell it, religion. The same religion that inspires the curriculum revisions so horrifying to a liberal sensibility also insulates its champions from susceptibility to logical argument and from self-doubt. Food for thought, even if a little difficult to swallow.

Nathan Schradle is a graduate student in the Religious Studies Program at NYU.

The Revisionaries will screen next at the AFI-Discovery Channel Silverdocs Festival on June 22 & 23—catch it if you’re in the Washington, DC area and check the film website for more screening dates as they are added!