Amy Levin: Those who find religion scholars to be an insular grouping of armchair academics, out of touch with the “real world” (a term said scholars enjoy deconstructing), might have been surprised to hear some of the panels at this year’s American Academy of Religion (AAR) Conference in San Francisco. Though the conference followed suit from previous years in its diversity of religions, ideas, and (inter)disciplines, many of the discussions trended towards a mix of religion, politics, the public sphere, democracy, grassroots organizing, peacebuilding, and secularism. You know, the “real stuff.”

Lisa Miller, an editor at Newsweek and keeper of the weekly Belief Watch column, taps into the academic space of public politics in this week’s column, “Is the black church the answer to liberal prayers?” She opens the conversation with the following: “As the American left continues to seek a coherent way to articulate its moral priorities in these days of political stalemates and widening income gaps, it might look to the most unlikely of places — the academy — for guidance and inspiration.” While I would hesitate to suggest that the “American left” and “the academy” have been in a long distance relationship up until now, Miller’s point is well taken.

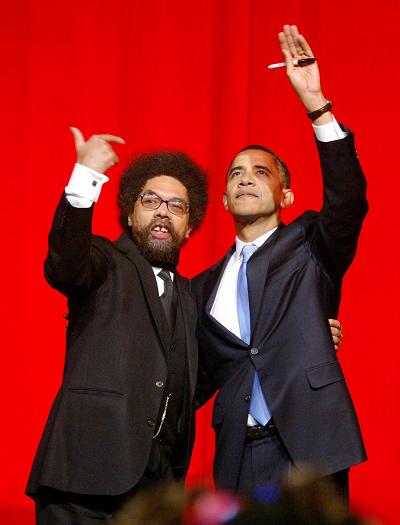

Miller’s “black church” is representative of a particular kind of African American liberal Christian intellectual, dedicated to the cause of “justice” as a public morality to fuel democracy – the most visible and outspoken of which include Cornel West, Rev. Jeremiah Wright, and Obery Hendricks. Miller interviews Hendricks between AAR panels in San Francisco, who described his hermeneutic of justice in his interpretation of the bible. Hendrick’s arguments resonate with other liberation theologians and progressive Christians who say that Jesus was a “class warrior” whose foremost concern is with inequality, and that true Christians are those that support government programs that help people.

So why the sudden turn toward academic religionists to help give voice to liberals? And what exactly does academia offer that non-academic public discourse cannot? Can we, and why do we separate the two? Hendricks doesn’t exactly tell us, but seems to say that liberals have too easily passed the moral baton to Christian conservatives, claiming that liberals, “have ceded the moral ground and the religious ground to the Christian conservatives who violate the very faith they purport to support.”

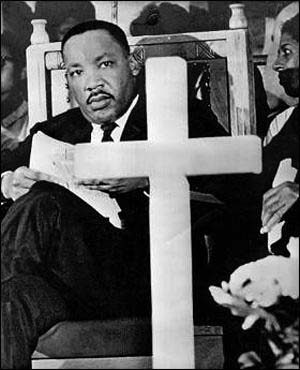

But Miller does offer up reason for why the particular politics of academia might better serve a moral liberal platform for our current all-too-secular, or so we hear, democrats. “Politicians have to be pragmatic, but preachers and professors do not,” Miller says. “The social justice message of the black church, framed by culture’s outsiders and forged through hardship, might help guide the diffuse and disconsolate left through troubled times.”

Academic liberal theology reminds us that if we’re reaching for true democracy as a nation, we should be listening equally to all sides of the coin, and that includes the religious, whether progressive or conservative. That conservatives are much better at making use of their faith-in-common than liberals is without doubt. But are the liberal theologies of these intellectuals descriptively “academic” by virtue of, say, Cornel West-as-professor? What contributions to the public discourse does academia legitimize — more than, say, grassroots, faith-based liberal coalitions? Before we decide how to best mobilize liberals to speak faithfully, we might want to consider who exactly in our country holds the power, and whether or not liberals needs more faith, or just more organizing.

Amy Levin is a graduate student in Religious Studies at New York University and a regular contributor to The Revealer. She is a permablogger at Feminism and Religion.