Maggie Zhang

Inhibitory control and emotional regulation have long term implications for academic achievement and social functioning starting in early childhood (Anzman-Frasca, Francis, & Birch, 2015; Blandon, Calkins, & Keane, 2010; Carlson & Wang, 2007; Fan, Liberman, Keysar, & Kinzler, 2015; King, Lengua, & Monahan, 2013; Oades-Sese et al., 2011; Rhoades, Greenberg, & Domitrovich, 2009). Both emotional regulation and inhibitory control have underpinnings in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, suggesting that there may be a link between these two processes (Blair, 2002; Martin & Ochsner, 2016; Ochsner & Gross, 2005). Inhibitory control is a cognitive skill that refers to the ability to control one’s thoughts and actions and facilitates children’s emotional regulation, which allows an individual to respond appropriately in social situations (Carlson & Wang, 2007; Hudson & Jacques, 2014; Šimleša, Cepanec, & Marta Ljubešić, 2017). Past research has highlighted the potential advantages of early exposure to or fluency in more than one language for inhibitory control, suggesting that early childhood bilinguals exhibit greater inhibitory control than monolinguals (Bialystok, 2017; Bialystok, Martin, & Viswanathan, 2005). Thus, it seems plausible that early childhood bilingualism might strengthen the relation between inhibitory control and emotional regulation. Therefore, the current review explores the following research question: Does inhibitory control enriched by early childhood bilingualism promote positive emotional regulation development? This paper focuses on research conducted with bilingual participants, in English and another language, who were exposed to both languages at home, at school, or with family members at least 10-25% of the time every day since birth (Byers-Heinlein & Lew-Williams, 2013). Emotional Regulation and Inhibitory Control

The development of inhibitory control and emotional regulation begins in early childhood (Anzman-Frasca et al., 2015; Carlson & Wang, 2007; Rhoades et al., 2009). Researchers exploring the relation between inhibitory control and emotional regulation typically create a scenario where the child receives a disappointing gift at the end of participating in a research study and have found that children who had higher levels of inhibitory control were significantly better at regulating their emotions and masking their disappointment by still reacting positively when receiving the gift (Carlson & Wang, 2007; Hudson & Jacques, 2014). By contrast, children with lower levels of inhibitory control had difficulty hiding their negative emotionality and looked or acted visibly upset over the gift (Carlson & Wang, 2007; Hudson & Jacques, 2014).

Emotional regulation is essential for child development and has implications for academic achievement and social functioning (Birch & Ladd, 1997; Eisenberg et al., 1995; English et al., 2012; Graziano, Reavis, Keane, & Calkins, 2007; Gumora & Arsenio, 2002; Rydell, Thorell, & Bohlin, 2007; Trentacosta & Shaw, 2009; Valiente et al., 2010). Beginning in early childhood, emotional regulation predicts preschoolers’ academic achievement; students who display more emotional regulation have stronger relationships with their teachers, which, in turn, contributes to higher rates of early academic success and productivity (Birch & Ladd, 1997; Graziano et al., 2007; Gumora & Arsenio, 2002; Valiente et al., 2010). Emotional regulation also impacts social behaviors starting in preschool, with teachers and peers viewing students who have a greater ability to self-regulate and positive social relationships, more favorably (Birch & Ladd, 1997; Blair, Denham et al., 2004; Eisenberg et al., 1996; Graziano et al., 2007; McDowell, Kim, O’Neil, & Parke, 2002). Thus, inquiry into the mechanisms that enrich the associations between inhibitory control and emotional regulation is of particular importance. Once such mechanism might be childhood bilingualism.

Early Childhood Bilingualism Enriches Inhibitory Control

The Bilingual Inhibitory Control Advantage (BICA) argument speculates that bilinguals perform better than monolinguals on tasks that require inhibitory control (Green, 1998). This argument is supported by research that has found that bilinguals demonstrate more instances of inhibitory control than monolinguals (Bialystok et al., 2005; Bialystok, 2017). One possible explanation for this advantage is that bilinguals simultaneously use one language while inhibiting interferences from the other language (Esposito, Baker-Ward, & Mueller, 2013; Hannaway, Opitz, & Sauseng, 2019). The active suppression of the second language, while using the intended one, demonstrates inhibitory control.

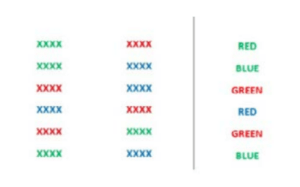

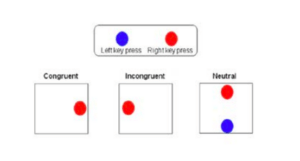

The most common method for measuring the relation between bilingualism and inhibitory control is through tasks such as the Stroop and Simon Tasks (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Both tasks require participants to focus on one aspect of the task while ignoring irrelevant information, a core element of inhibitory control (Stevens & Bavelier, 2012). Supporting the BICA hypothesis, bilinguals were found to have higher instances of inhibitory control compared to monolinguals on both tasks, such that bilinguals were better able to suppress contradictory stimuli (e.g., the color of the word) and reacted faster than monolinguals (Bialystok et al., 2005; Bialystok, 2017; Blumenfeld & Marian, 2011; Esposito et al., 2013; Hartanto & Yang, 2019). Literature Reviews | 7 OPUS (2020) 11:1

Given that bilinguals outperform monolinguals on tasks such as the Simon and Stoop Tasks, it is important to explore how early childhood bilingualism could be a factor that enhances inhibitory control and emotional regulation in children raised in bilingual households (Fan et al., 2015; Oades-Sese et al., 2011). In fact, greater inhibitory control is associated with greater social skills and academic achievement in bilingual children, due to their ability to control or adjust their behaviors in response to challenging situations and thereby more easily self-regulate (Carlson & Wang, 2007; Hartanto & Yang, 2019; Hilchey & Klein, 2011; Liu et al., 2019; Lukasik et al., 2018; Rhoades et al., 2009). Since early childhood bilingualism enriches inhibitory control and inhibitory control is linked with emotional regulation, growing up in a bilingual household could promote emotional regulation and effective communication (Fan et al., 2015; Oades-Sese et al., 2011). In fact, bilingual children as young as four-years-old have a greater ability to inhibit negative emotions in social settings and show more flexibility when responding to social situations, such as reacting calmly and positively to a disagreement (Carlson & Wang, 2007; Denham et al., 2003; Fan et al., 2015; Oades-Sese et al., 2011). Both emotional regulation and inhibitory control are necessary for bilinguals to restrain their own thoughts and actions in frustrating moments, enabling them to appear more emotionally regulated and deemed as likeable by their peers (Fan et al., 2015). Early childhood bilingualism thus appears to serve as a moderator for the relation between inhibitory control and emotional regulation, although more research on this topic is needed.

Conclusion

Past findings support the BICA hypothesis, with bilinguals exhibiting greater inhibitory control and emotional regulation compared to monolinguals (Bialystok et al., 2005; Bialystok, 2017; Blumenfeld & Marian, 2011; Esposito et al., 2013; an et al., 2015; Hartanto & Yang, 2019; Oades-Sese et al., 2011). These advantages in inhibitory control and emotional regulation are noteworthy, because early childhood bilingualism could potentially offer an explanation for the greater academic achievement and social functioning in bilinguals compared to their monolingual peers (Fan et al., 2015; Oades-Sese et al., 2011).

Although a robust amount of literature has examined early childhood bilingualism, future research should examine how the development of inhibitory control differs for people bilingual in English and another written language, such as Spanish, compared to people bilingual in character based languages (e.g., Chinese). Additionally, to see the long term effects of early childhood bilinguals, more longitudinal studies should be conducted in order to see how early childhood bilingualism impacts the development of inhibitory control throughout their life, rather than conducting comparison studies for one age group at a time. These findings can have implications in practice and policy by emphasizing the importance of offering different language exposure in schools. Given the growing amount of bilingual children in the United States, research should support the importance of bilingual schooling, especially in communities with large immigrant populations.

References

Anzman-Frasca, S., Francis, L. A., & Birch, L. L. (2015). Inhibitory control is associated with psychosocial, cognitive, and weight outcomes in a longitudinal sample of girls. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 1(3), 203-216.

Bialystok, E. (2017). The bilingual adaptation: How minds accommodate experience. Psychological Bulletin, 143(3), 233-262.

Bialystok, E., Martin, M. M., & Viswanathan, M. (2005). Bilingualism across the lifespan: The rise and fall of inhibitory control. International Journal of Bilingualism, 9(1), 103–119.

Birch, S. H., & Ladd, G. W. (1997). The teacher-child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology, 35(1), 61-79.

Blair, K. A., Denham, S. A., Kochanoff, A., & Whipple, B. (2004). Playing it cool: Temperament, emotion regulation, and social behavior in preschoolers. Journal of School Psychology, 42(6), 419-443.

Blair, C. (2002). School readiness. American Psychologist, 57(2), 111-127. Blandon, A. Y., Calkins, S. D., & Keane, S. P. (2010). Predicting emotional and social competence during early childhood from toddler risk and maternal behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 119-132.

Blumenfeld, H. K., & Marian, V. (2011). Bilingualism influences inhibitory control in auditory comprehension. Cognition, 118(2), 245-257.

Byers-Heinlein, K., & Lew-Williams, C. (2013). Bilingualism in the early years: What the science says. LEARNing Landscapes, 7(1), 95-112. Carlson, S. M., & Wang, T. S. (2007). Inhibitory control and emotion regulation in preschool children. Cognitive Development, 22(4), 489-510.

Denham, S. A., Blair, K. A., DeMulder, E., Levitas, J., Sawyer, K., Auerbach-Major, S., & Queenan, P. (2003). Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence? Child Development, 74(1), 238-256.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Murphy, B., Karbon, M., Smith, M., & Maszk, P. (1996). The relations of children’s dispositional empathy-related responding to their emotionality, regulation, and social functioning. Developmental Psychology, 32(2), 195-209.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Murphy, B., Maszk, P., Smith, M., & Karbon, M. (1995). The role of emotionality and regulation in children’s social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development, 66(5), 13-60.

English, T., John, O. P., Srivastava, S., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Emotion regulation and peer-rated social functioning: A four-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(6), 780-784.

Esposito, A. G., Baker-Ward, L., & Mueller, S. T. (2013). Interference suppression vs. response inhibition: An explanation for the absence of a bilingual advantage in preschoolers’ stroop task performance. Cognitive Development, 28(4), 354-363.

Fan, S. P., Liberman, Z., Keysar, B., & Kinzler, K. D. (2015). The exposure advantage. Psychological Science, 26(7), 1090-1097.

Graziano, P. A., Reavis, R. D., Keane, S. P., & Calkins, S. D. (2007). The role of emotion regulation in children’s early academic success. Journal of School Psychology, 45(1), 3-19.

Green, D. W. (1998). Mental control of the bilingual lexicosemantic system. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1(2), 67-81.

Gumora, G., & Arsenio, W. F. (2002). Emotionality, emotion regulation, and school performance in middle school children. Journal of School Psychology, 40(5), 395-413.

Hannaway, N., Opitz, B., & Sauseng, P. (2019). Exploring the bilingual advantage: Manipulations of similarity and second language immersion in a stroop task. Cognitive Neuroscience, 10(1), 1-12.

Hartanto, A., & Yang, H. (2019). Does early active bilingualism enhance inhibitory control and monitoring? A propensitymatching analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 45(2), 360-378.

Hilchey, M., & Klein, R. (2011). Are there bilingual advantages on nonlinguistic interference tasks? Implications for the plasticity of executive control processes. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18(4), 625-658.

Hudson, A., & Jacques, S. (2014). Put on a happy face! Inhibitory control and socioemotional knowledge predict emotion regulation in 5- to 7-year-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 123, 36-52. King, K.,

Lengua, L., & Monahan, K. (2013). Individual differences in the development of self-regulation during pre-adolescence: Connections to context and adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(1), 57-69.

Liu, C., Yang, C., Jiao, L., Schwieter, J. W., Sun, X., & Wang, R. (2019). Training in language switching facilitates bilinguals’ monitoring and inhibitory control. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 18-39.

Lukasik, K. M., Lehtonen, M., Soveri, A., Waris, O., Jylkkä, J., & Laine, M. (2018). Bilingualism and working memory performance: Evidence from a large-scale online study. PLoS One, 13(11), 1-16.

Martin, R. E., & Ochsner, K. N. (2016). The neuroscience of emotion regulation development: Implications for education. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 10, 142- 148. References Literature Reviews | 9 Bilingualism, Inhibition and Emotion

McDowell, D. J., Kim, M., O’Neil, R., & Parke, R. D. (2002). Children’s emotional regulation and social competence in middle childhood. Marriage & Family Review, 34(3-4), 345-364.

Oades-Sese, G. V., Esquivel, G. B., Kaliski, P. K., & Maniatis, L. (2011). A longitudinal study of the social and academic competence of economically disadvantaged bilingual preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 47(3), 747- 764.

Ochsner, K. N., & Gross, J. J. (2005). The cognitive control of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(5), 242-249.

Rhoades, B. L., Greenberg, M. T., & Domitrovich, C. E. (2009). The contribution of inhibitory control to preschoolers’ social–emotional competence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(3), 310-320.

Rydell, A., Thorell, L. B., & Bohlin, G. (2007). Emotion regulation in relation to social functioning: An investigation of child self-reports. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 4(3), 293-313.

Šimleša, S., Cepanec, M., & Ljubešić, M. (2017). The role of executive functions in language comprehension in preschool children. Psychology, 8(2), 227-245.

Stevens, C., & Bavelier, D. (2012). The role of selective attention on academic foundations: A cognitive neuroscience perspective. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 2(1), S48.

Trentacosta, C. J., & Shaw, D. S. (2009). Emotional self-regulation peer rejection, and antisocial behavior: Developmental associations from early childhood to early adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(3), 356- 365.

Valiente, C., Lemery-Chalfant, K., & Swanson, J. (2010). Prediction of kindergartners’ academic achievement from their effortful control and emotionality. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 550-560.

Figure 1. The Stroop Task presents the word of the color associated with a different color. For example, the word presented is “red” but the color of the ink is in green. Participants are then asked to say the color of the ink instead of the word.

Figure 2. The Simon Task has participants press the left key if the blue circle appears and the right key if the red circle appears.

Leave a Reply