Transnational Memory Making Among New York’s Japanese “Old Left”

Today’s post is authored by Melissa Redwood, a doctoral candidate focusing on Asian American history and the transnational study of race and gender in the 20th century at Yale University and a Cold War Dissertation Fellow at the Tamiment Library.

The Tamiment Library is home to a valuable repository of materials made by and for the Japanese immigrant community in New York City, especially in the post-World War II period. In particular, the Isaku and Emi Kida Papers and the Karl Ichiro Akiya Papers both contain a wealth of Japanese-language newspaper clippings and correspondence shared between the Japanese American cultural and intellectual left. These papers testify to an effort among this small community to play an active role in the terms by which their work and identity would be remembered.

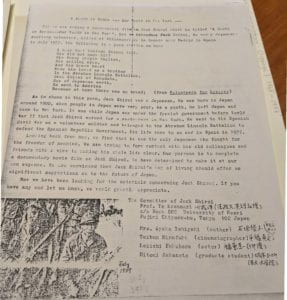

Flyer titled “A Death in Spain—Our Youth in New York” that was produced in an effort to find information on Jack Shirai. Karl Ichiro Akiya Papers (TAM.236).

In browsing these papers, I was particularly struck by the communal effort to recover and publicize the memory of Jack Shirai, a cook who lived in Greenwich Village in the 1930s who would go on to fight and die in the Spanish Civil War. As a member of the Japanese Workers’ Club, a group affiliated with the Japanese language section of the Communist Party USA, Shirai felt a strong commitment to fighting against fascism on both the local and global stage. Moreover, as the only Japanese national to fight and die in the Spanish Conflict, his conspicuous presence on the roster would go on to hold a unique symbolic significance for both the Japanese and Japanese American left.

As Japan began its wartime mobilization in the 1930s, Shirai and other like-minded Japanese nationals spoke out against their home government at great personal risk. Even while living abroad, they faced political pressure and surveillance from the Japanese government and Japanese American social institutions. While those who lived in New York were more insulated from the Japanese immigrant center of power on the west coast, according to Ayako Ishigaki (a friend and contemporary of Shirai’s), they remained subject to aggressive physical intimidation from a patriotic political group. At the same time, Ishigaki wrote about the mutual support of the Japanese American “old left” community in face of this harassment; when she was targeted for her particular visibility as a Japanese woman in the antiwar movement, Ishigaki noted the role which Shirai and others played in defending and protecting her from her would-be assailants.[1]

Karl Akiya’s papers include several letters in Japanese from Ishigaki and others regarding an effort to retrieve and contact Shirai’s former acquaintances who might still be living in New York. The aim was to put together a documentary film to broadcast on Japan’s national broadcasting network, NHK.

![Article titled “Sono shi ga ima toikakeru mono wa [What that death asks us now]” by Seki Kōzō, from an unidentified periodical, 1983. From the Karl Ichiro Akiya Papers (TAM.236).](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wp.nyu.edu/dist/d/2418/files/2020/03/folder-26-ishigaki-Page-107-232x300.jpg)

Article titled “Sono shi ga ima toikakeru mono wa [What that death asks us now]” by Seki Kōzō, from an unidentified periodical, 1983. Karl Ichiro Akiya Papers (TAM.236).

As the “Old Left” generation was aging and growing thinner, recovering this history thus served as a way of documenting their own values of communal struggle against—and in the face of—political repression. As the majority of these documents are in Japanese, and in many ways contradict the “model minority” stereotype, they are often left out of “traditional” narratives of Japanese American history. These papers, therefore, provide a significant window into the historical self-fashioning of this political cohort of the 1930s, and the position which they envisioned for themselves at the margins of nationalist histories.

[1] Ayako Ishigaki, Supein de tatakatta Nihonjin [The Japanese Who Fought in Spain] (Tokyo: Asahi Bunko, 1989) p. 34-35.

[2] “A Death in Spain—Our Youth in New York,” undated; Karl Ichiro Akiya Papers; TAM 236; Box 2, Folder 26; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

[3] Seki Kōzō, “Sono shi ga ima toikakeru mono wa [What that death asks us now],” Unlabeled periodical, 17 July 1983; Karl Ichiro Akiya Papers; TAM 236; Box 2, Folder 26; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.