I think I might have a problem with the international language of music

I consider myself fortunate for participating in Yo-Yo Ma’s workshop with The Silk Road Ensemble a couple of days back. I found it quite humbling when my oud professor – a class I had started taking only two short months ago – recommended me for the two-day rendezvous with incredibly talented musicians, some of whom had visited Yugoslavia long before I was even born. It was truly an honor, as I am a firm believer that music can act as a catalyst of dialogue that outgrows language and verbal communication.

However, reading excerpts from “Rebel Music” on jazz ambassadors during the Cold War and the international language of music with my background (or ‘professional deformation’) of a Political Science student, I could not help but wonder about the number of contested boxes the concept of an international language of music is hidden inside. I believe this concept comes with political baggage and I will try to unpack some aspects of it in this blog.

***

Music is a powerful tool and quite an impactful conveyor of particular messages; namely, the one that the Silk Road Ensemble had in mind was that music can be made anywhere with anything and that is where its indigenous beauty hides. It easily surpasses man-made borders and penetrates artificially mandated walls. Given that words can, at times, be more impactful than physically hitting a person, so can music turn out to be more powerful, at times, than cold weapons.

The excerpt from “Rebel Music” we have read last week focuses on precisely this concept of musical ambassadorship in the harshest of times for the international community. In the historical moment of political deafness, the tool you use to revive one’s voice and sense of hearing would definitely be music. What I saw in the Silk Road Ensemble is precisely that musical/cultural diplomacy with remnants from the Cold War jazz ambassadorship, but repacked into a finer tuned box of neoliberalist visionary because the Cold War version had expired in 1989.

The first similarity I saw was the diversity from the mainstream that makes the body of the ensemble. For jazz ambassadors, being African-American and representing the openness of the United States in the world was more than an accomplishment at such a peculiar time in history. Those musicians representing a very particular niche in music were chosen and ‘guided’ by the U.S. State Department to paint a different picture of the U.S. in the world when the global audience was anxiously anticipating which side would pull the trigger first. The U.S. pulled a cultural diplomacy card from its sleeve and put it on the table in the form of African-American jazz musicians. It also pulled the same card on its own domestic audience, as one cannot go without the other. It was diplomacy without a par on both the domestic and the international level.

Today, along the same lines, the Silk Road Ensemble musicians represent a cultural diversity that differs from mainstream representations in music and the American society. The musicians bring their cultural legacies with them and regionally acknowledged instruments to make a barzakh between Western-style/classical and other, more traditional, musical traditions.

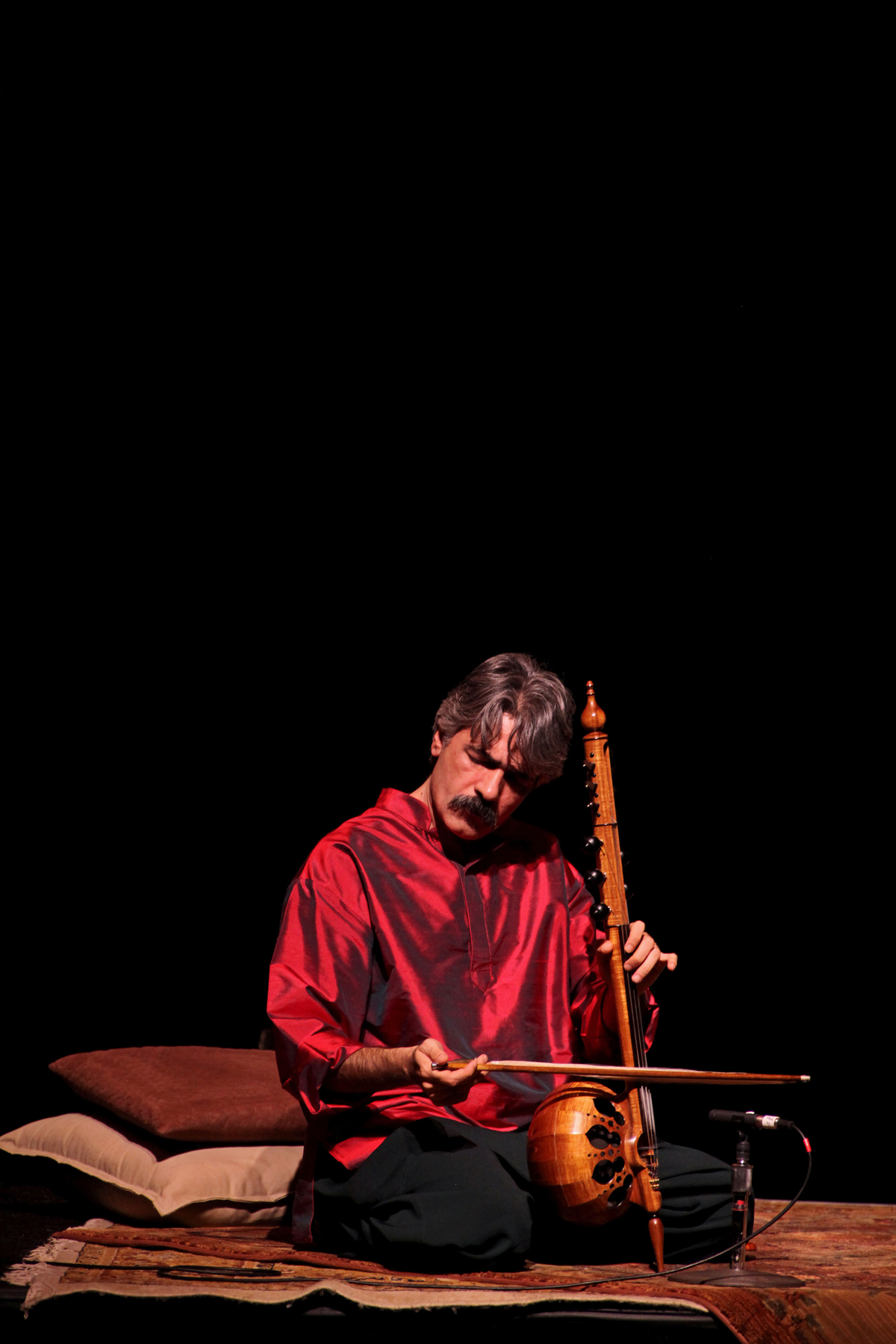

The musicians I had the chance of working with come from Syria (Kinan Azmeh), Japan (Wu Tong), Iran (Kayhan Kalhor) and India (Sandeep Das), among many others. I had no idea that instruments called shang or kamancheh existed before being exposed to them during the workshop. I also had no idea they went so well with the violin or the bass. Or that one can play Johan Sebastian Bach’s sonatas along with a traditional Taiwanese love song. The ensemble speaks to this by saying that the Western and the non-Western musical traditions shared a lot more historically than they do now and that people should not forget that.

The Silk Road Ensemble on a tour

What I have to note in regards to diversity of musicians in the Silk Road Ensemble is that, at the end of the day, they all reside, work or teach in the U.S. They have mostly been musically educated in their own traditions, but how much of their own authentic legacies they represent by being a part of a U.S.-funded and a U.S.-guided orchestra that works in such a way that their traditions are being adjusted to Western standards in one way or another. How does that orchestra speak to a global language of music, then? Many of them finished their musical education in the U.S. and now work and reside in the U.S. How much justice do they do to their regional musical streams, then?

I suppose equality of all players should be discussed before the game starts. This brings me to my next point – neoliberal musicality or jazz ambassadorship Vol. 2.

Even though I risk being too extreme in my view, I believe there is no global language of music that incorporates all of its regional diodes equally. The power play between different regions in establishing the supremacy over that language will never stop being active. We can clearly see that ‘flight of the bumblebee’ rollercoaster in jazz ambassadorship during the Cold War.

This power play exists even today and has no close expiration date. Until then, I firmly believe that the international language of music establishes and further realizes hegemonic grips, in cultural terms or otherwise, of Western-style musicalities over all others. The fact that this barzakh of genres is being present to global audiences worldwide does not make it less Western, given that all of the non-Western traditions had to be adjusted, to differing extents, to the Western paradigm of musical thought. The Indian tabla musician, Sandeep Das, had to conquer the skill of musical notations, even though there is no such thing as a rhythm or a written musical system in the musical family of tabla.

His popularity as a tabla musician is, therefore, confined to solo concerts mostly in India, whereas his talent in the U.S. and worldwide has been primarily heard within the context of the Silk Road Ensemble. One other member, Cristina Pato, started a festival in her local Galician community in Spain because of the wind that her work with the Ensemble gave her globally. To that extent, I do have to acknowledge that regional and local instruments, such as the Indian tabla and the Iranian kamancheh, are being globally advertised through such international tours.

Keyhan Kalhor with his camancheh

However, the kamancheh instrument still needs to be presented in the context of a Western-assembled ensemble and along the name of Western-acclaimed Yo-Yo Ma to establish a platform of representation for itself to the audience. Does that not speak to neoliberalist rhetoric of Western powers that insidiously penetrate local customs and cultures under the ‘we are all equal, come join us’ banner? To this extent, the West also benefits from having such an ensemble, as it can say it is being inclusive and globally aware. Such initiatives of bridging cultural gaps usually come from the West nowadays. Diversifying and expanding beyond Western mainstream tradition of classical music is the key to achieving universality, in this case. This quite strongly resembles the U.S. State Department narrative with jazz ambassadorship from the Cold War.

To an extent, I saw a clear connection with jazz ambassadors of the Cold War who went out and preached about American openness and diversity to the world, but the musicians themselves were being almost fetishized by the system/the government of the time that funded them. Their music was being used by powers that far outgrew them. They had a political agenda that encapsulated the free will of their music. Obviously, they became known through their tours and greatly benefited from the program. Not to say that they haven’t gotten anything out of it, to the contrary, but the fact remains that their ‘subculture jazz exoticism’, as jazz was never fully a mainstream genre at the time, was used in a slightly culturally perverted way. And I saw elements of that in the Silk Road Ensemble. I, obviously, respect their work tremendously, buy I cannot help but wonder about the politics-free nature of their mission and the rhetoric of the international language of music they are spreading across the globe. What if we are seeing the same box from the Cold War, just repackaged to fit our current times with the expired date just being covered by the new one? And if this is the case, what is the alternative to it? What international language should I believe in, then?

At the end, I have to add that the Silk Road Ensemble forms an incredible barzakh between different musical traditions and that their work does cross political walls and national boundaries; however, they do not have to roll under the paradigm of an international language of music as an ambassadorship to achieve what they are achieving. Their work speaks for itself, I believe.

Sources:

Leave a Reply