The title of this post is also the title of a tutorial I’m giving at ISMIR 2016 with Jan Van Balen and Dan Brown. The conference is organized by the International Society for Music Information Retrieval, and it’s the fanciest of its kind. You may be wondering what Music Information Retrieval is. MIR is a specialized field in computer science devoted to teaching computers to understand music, so they can transcribe it, organize it, find connections and similarities, and, maybe, eventually, create it.

So why are we going to talk to the MIR community about hip-hop? So far, the field has mostly studied music using the tools of Western classical music theory, which emphasizes melody and harmony. Hip-hop songs don’t tend to have much going on in either of those areas, which makes the genre seem like it’s either too difficult to study, or just too boring. But the MIR community needs to find ways to engage this music, if for no other reason than the fact that hip-hop is the most-listened to genre in the world, at least among Spotify listeners.

Hip-hop has been getting plenty of scholarly attention lately, but most of it has been coming from cultural studies. Which is fine! Hip-hop is culturally interesting. When humanities people do engage with hip-hop as an art form, they tend to focus entirely on the lyrics, treating them as a subgenre of African-American literature that just happens to be performed over beats. And again, that’s cool! Hip-hop lyrics have literary interest. If you’re interested in the lyrical side, we recommend this video analyzing the rhyming techniques of several iconic emcees. But what we want to discuss is why hip-hop is musically interesting, a subject which academics have given approximately zero attention to.

Much of what I find exciting (and difficult) about hip-hop can be found in Kanye West’s song “Famous” from his album The Life Of Pablo.

The song comes with a video, a ten minute art film that shows Kanye in bed sleeping after a group sexual encounter with his wife, his former lover, his wife’s former lover, his father-in-law turned mother-in-law, various of his friends and collaborators, Bill Cosby, George Bush, Taylor Swift, and Donald Trump. There’s a lot to say about this, but it’s beyond the scope of our presentation, and my ability to verbalize thoughts. The song has some problematic lyrics. Kanye drops the n-word in the very first line and calls Taylor Swift a bitch in the second. He also speculates that he might have sex with her, and that he made her famous. I find his language difficult and objectionable, but that too is beyond the scope. Instead, I’m going to focus on the music itself.

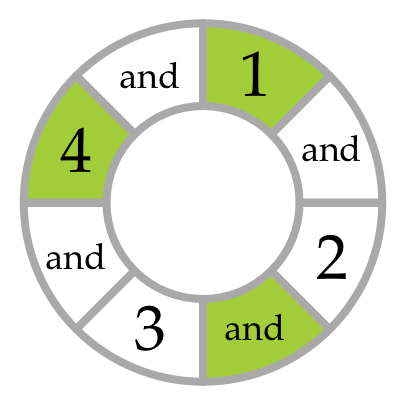

“Famous” has a peculiar structure, shown in the graphic below.

The track begins with a six bar intro, Rihanna singing over a subtle gospel-flavored organ accompaniment in F-sharp major. She’s singing few lines from “Do What You Gotta Do” by Jimmy Webb. This song has been recorded many times, but for Kanye’s listeners, the most significant one is by Nina Simone.

Next comes a four-bar groove, a more aggressive organ part over a drum machine beat, with Swizz Beatz exclaiming on top. The beat is a minimal funk pattern on just kick and snare, treated with cavernous artificial reverb. The organ riff is in F-sharp minor, which is an abrupt mode change so early in the song. It’s sampled from the closing section of “Mi Sono Svegliato E…Ho Chiuso Gli Occhi” by Il Rovescio della Medaglia, an Italian prog-rock band I had never heard of until I looked the sample up just now. The song is itself built around quotes of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier–Kanye loves sampling material built from samples.

Verse one continues the same groove, with Kanye alternating between aggressive rap and loosely pitched singing. Rap is widely supposed not to be melodic, but this idea collapses immediately under scrutiny. The border between rapping and singing is fluid, and most emcees cross it effortlessly. Even in “straight” rapping, though, the pitch sequences are deliberate and meaningful. The pitches might not fall on the piano keys, but they are melodic nonetheless.

The verse is twelve bars long, which is unusual; hip-hop verses are almost always eight or sixteen bars. The hook (the hip-hop term for chorus) comes next, Rihanna singing the same Jimmy Webb/Nina Simone quote over the F-sharp major organ part from the intro. Swizz Beatz does more interjections, including a quote of “Wake Up Mr. West,” a short skit on Kanye’s album Late Registration in which DeRay Davis imitates Bernie Mac.

Verse two, like verse one, is twelve bars on the F-sharp minor loop. At the end, you think Rihanna is going to come back in for the hook, but she only delivers the pickup. The section abruptly shifts into an F-sharp major groove over fuller drums, including a snare that sounds like a socket wrench. The lead vocal is a sample of “Bam Bam” by Sister Nancy, which is a familiar reference for hip-hop fans–I recognize it from “Lost Ones” by Lauryn Hill and “Just Hangin’ Out” by Main Source. The chorus means “What a bum deal.” Sister Nancy’s track is itself sample-based–like many reggae songs, it uses a pre-existing riddim or instrumental backing, and the chorus is a quote of the Maytals.

Kanye doesn’t just sample “Bam Bam”, he also reharmonizes it. Sister Nancy’s original is a I – bVII progression in C Mixolydian. Kanye pitch shifts the vocal to fit it over a I – V – IV – V progression in F-sharp major. He doesn’t just transpose the sample up or down a tritone; instead, he keeps the pitches close by changing their chord function. Here’s Sister Nancy’s original:

And here’s Kanye’s version:

The pitch shifting gives Sister Nancy the feel of a robot from the future, while the lo-fidelity recording places her in the past. It’s a virtuoso sample flip.

After 24 bars of the Sister Nancy groove, the track ends with the Jimmy Webb hook again. But this time it isn’t Rihanna singing. Instead, it’s a sample of Nina Simone herself.It reminds me of Kanye’s song “Gold Digger“, which includes Jamie Foxx imitating Ray Charles, followed by a sample of Ray Charles himself. Kanye is showing off here. It would be a major coup for most producers to get Rihanna to sing on a track, and it would be an equally major coup to be able to license a Nina Simone sample, not to mention requiring the chutzpah to even want to sample such a sacred and iconic figure. Few people besides Kanye could afford to use both Rihanna and Nina Simone singing the same hook, and no one else would dare. I don’t think it’s just a conspicuous show of industry clout, either; Kanye wants you to feel the contrast between Rihanna’s heavily processed purr and Nina Simone’s stark, preacherly tone.

Here’s a diagram of all the samples and samples of samples in “Famous.”

In this one track, we have a dense interplay of rhythms, harmonies, timbres, vocal styles, and intertextual meaning, not to mention the complexities of cultural context. This is why hip-hop is interesting.

You probably have a good intuitive idea of what hip-hop is, but there’s plenty of confusion around the boundaries. What are the elements necessary for music to be hip-hop? Does it need to include rapping over a beat? When blues, rock, or R&B singers rap, should we retroactively consider that to be hip-hop? What about spoken-word poetry? Does hip-hop need to include rapping at all? Do singers like Mary J. Blige and Aaliyah qualify as hip-hop? Is Run-DMC’s version of “Walk This Way” by Aerosmith hip-hop or rock? Is “Love Lockdown” by Kanye West hip-hop or electronic pop? Do the rap sections of “Rapture” by Blondie or “Shake It Off” by Taylor Swift count as hip-hop?

If a single person can be said to have laid the groundwork for hip-hop, it’s James Brown. His black pride, sharp style, swagger, and blunt directness prefigure the rapper persona, and his records are a bottomless source of classic beats and samples. The HBO James Brown documentary is a must-watch.

Wikipedia lists hip-hop’s origins as including funk, disco,

‘electronic music, dub, R&B, reggae, dancehall, rock, jazz, toasting, performance poetry, spoken word, signifyin’, The Dozens, griots, scat singing, and talking blues. People use the terms hip-hop and rap interchangeably, but hip-hop and rap are not the same thing. The former is a genre; the latter is a technique. Rap long predates hip-hop–you can hear it in classical, rock, R&B, swing, jazz fusion, soul, funk, country, and especially blues, especially especially the subgenre of talking blues. Meanwhile, it’s possible to have hip-hop without rap. Nearly all current pop and R&B are outgrowths of hip-hop. Turntablists and controllerists have turned hip-hop into a virtuoso instrumental music.

It’s sometimes said that rock is European harmony combined with African rhythm. Rock began as dance music, and rhythm continues to be its most important component. This is even more true of hip-hop, where harmony is minimal and sometimes completely absent. More than any other music of the African diaspora, hip-hop is a delivery system for beats. These beats have undergone some evolution over time. Early hip-hop was built on funk, the product of what I call The Great Cut-Time Shift, as the underlying pulse of black music shifted from eighth notes to sixteenth notes. Current hip-hop is driving a Second Great Cut-Time Shift, as the average tempo slows and the pulse moves to thirty-second notes.

Like all other African-American vernacular music, hip-hop uses extensive syncopation, most commonly in the form of a backbeat. You can hear the blues musician Taj Mahal teach a German audience how to clap on the backbeat. (“Schvartze” is German for “black.”) Hip-hop has also absorbed a lot of Afro-Cuban rhythms, like the omnipresent son clave. This traditional Afro-Cuban rhythm is everywhere in hip-hop: in the drums, of course, but also in the rhythms of bass, keyboards, horns, vocals, and everywhere else. You can hear son clave in the snare drum part in “WTF” by Missy Elliott.

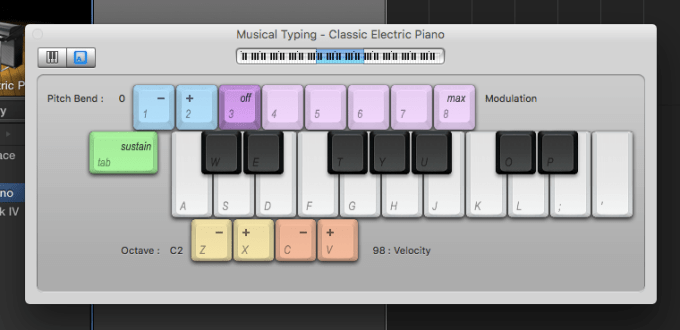

The NYU Music Experience Design Lab created the Groove Pizza app to help you visualize and interact with rhythms like the ones in hip-hop beats. You can use it to explore classic beats or more contemporary trap beats. Hip-hop beats come from three main sources: drum machines, samples, or (least commonly) live drummers.

Hip-hop was a DJ medium before emcees became the main focus. Party DJs in the disco era looped the funkiest, most rhythm-intensive sections of the records they were playing, and sometimes improvised toasts on top. Sampling and manipulating recordings has become effortless in the computer age, but doing it with vinyl records requires considerable technical skill. In the movie Wild Style, you can see Grandmaster Flash beat juggle and scratch “God Make Me Funky” by the Headhunters and “Take Me To The Mardi Gras” by Bob James (though the latter song had to be edited out of the movie for legal reasons.)

The creative process of making a modern pop recording is very different from composing on paper or performing live. Hip-hop is an art form about tracks, and the creativity is only partially in the songs and the performances. A major part of the art form is the creation of sound itself. It’s the timbre and space that makes the best tracks come alive as much as any of the “musical” components. The recording studio gives you control over the finest nuances of the music that live performers can only dream of. Most of the music consists of synths and samples that are far removed from a “live performance.” The digital studio erases the distinction between composition, improvisation, performance, recording and mixing. The best popular musicians are the ones most skilled at “playing the studio.”

Hip-hop has drawn much inspiration from the studio techniques of dub producers, who perform mixes of pre-existing multitrack tape recordings by literally playing the mixing desk. When you watch The Scientist mix Ted Sirota’s “Heavyweight Dub,” you can see him shaping the track by turning different instruments up and down and by turning the echo effect on and off. Like dub, hip-hop is usually created from scratch in the studio. Brian Eno describes the studio as a compositional tool, and hip-hop producers would agree.

Aside from the human voice, the most characteristic sounds in hip-hop are the synthesizer, the drum machine, the turntable, and the sampler. The skills needed by a hip-hop producer are quite different from the ones involved in playing traditional instruments or recording on tape. Rock musicians and fans are quick to judge electronic musicians like hip-hop producers for not being “real musicians” because sequencing electronic instruments appears to be easier to learn than guitar or drums. Is there something lazy or dishonest about hip-hop production techniques? Is the guitar more of a “real” instrument than the sampler or computer? Are the Roots “better” musicians because they incorporate instruments?

Maybe we discount the creative prowess of hip-hop producers because we’re unfamiliar with their workflow. Fortunately, there’s a growing body of YouTube videos that document various aspects of the process:

Before affordable digital samplers became available in the late 1980s, early hip-hop DJs and producers did most of their audio manipulation with turntables. Record scratching demands considerable skill and practice, and it has evolved into a virtuoso form analogous to bebop saxophone or metal guitar shredding.

Hip-hop is built on a foundation of existing recordings, repurposed and recombined. Samples might be individual drum hits, or entire songs. Even hip-hop tracks without samples very often started with them; producers often replace copyrighted material with soundalike “original” beats and instrumental performances for legal reasons. Turntables and samplers make it possible to perform recordings like instruments.

The Amen break, a six-second drum solo, is one of the most important samples of all time. It’s been used in uncountably many hip-hop songs, and is the basis for entire subgenres of electronic music. Ali Jamieson gives an in-depth exploration of the Amen.

There are few artistic acts more controversial than sampling. Is it a way to enter into a conversation with other artists? An act of liberation against the forces of corporatized mass culture? A form of civil disobedience against a stifling copyright regime? Or is it a bunch of lazy hacks stealing ideas, profiting off other musicians’ hard work, and devaluing the concept of originality? Should artists be able to control what happens to their work? Is complete originality desirable, or even possible?

We look to hip-hop to tell us the truth, to be real, to speak to feelings that normally go unspoken. At the same time, we expect rappers to be larger than life, to sound impossibly good at all times, and to live out a fantasy life. And many of our favorite artists deliberately alter their appearance, race, gender, nationality, and even species. To make matters more complicated, we mostly experience hip-hop through recordings and videos, where artificiality is the nature of the medium. How important is authenticity in this music? To what extent is it even possible?

The “realness” debate in hip-hop reached its apogee with the controversy over Auto-Tune. Studio engineers have been using computer software to correct singers’ pitch since the early 1990s, but the practice only became widely known when T-Pain overtly used exaggerated Auto-Tune as a vocal effect rather than a corrective. The “T-Pain effect” makes it impossible to sing a wrong note, though at the expense of making the singer sound like a robot from the future. Is this the death of singing as an art form? Is it cheating to rely on software like this? Does it bother you that Kanye West can have hits as a singer when he can barely carry a tune? Does it make a difference to learn that T-Pain has flawless pitch when he turns off the Auto-Tune?

Hip-hop is inseparable from its social, racial and political environment. For example, you can’t understand eighties hip-hop without understanding New York City in the pre-Giuliani era. Eric B and Rakim capture it perfectly in the video for “I Ain’t No Joke.”

Given that hip-hop is the voice of the most marginalized people in America and the world, why is it so compelling to everyone else? Timothy Brennan argues that the musical African diaspora of which hip-hop is a part helps us resist imperialism through secular devotion. Brennan thinks that America’s love of African musical practice is related to an interest in African spiritual practice. We’re unconsciously drawn to the musical expression of African spirituality as a way of resisting oppressive industrial capitalism and Western hegemony. It isn’t just the defiant stance of the lyrics that’s doing the resisting. The beats and sounds themselves are doing the major emotional work, restructuring our sense of time, imposing a different grid system onto our experience. I would say that makes for some pretty interesting music.