In the last post, we explored the use of phrase structure rules in accounting for the internal structure of words and concluded, as we did for phrase structure rules and sentences, that phrase structure rules are not part of the explanatory arsenal of current linguistic theory. The word structures described by phrase structure rules are explained by independent principles. In particular, the “label” of a morphologically complex word or word-internal constituent is a function of the labels of its daughter constituents and general principles, including whatever (non-phrase structural) principles are implicated in explaining “extended projections” of lexical categories.

However, it may turn out to be the case that phrase structure rules can serve to explain how morphologically complex words are recognized in language processing. This post will explore some possibilities for the use of (word-internal) phrases structure rules in word recognition and highlight the issues involved.

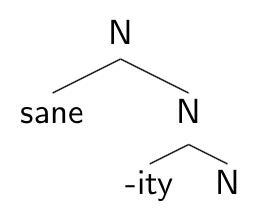

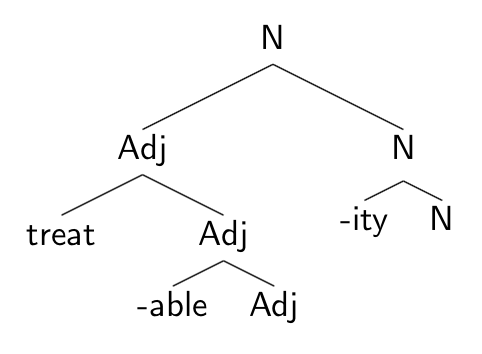

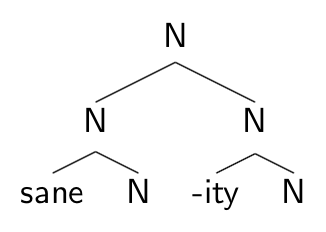

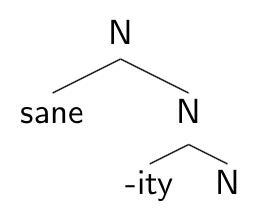

To begin, let’s look at some possible word structures, given our previous discussions of extended projections, c-selection, s-selection, feature-selection, and the possible different types of what have traditionally been called derivational morphemes. First, consider affixes like –ity, which attach to stems of a certain semantic sort (-ity s-selects for a property) and also feature-select for the identity of the head of the stems. For –ity, the set of heads that it feature-selects for include stems like sane and suffixes like –able and –al. The structure of sanity and treatability might look as below:

Rather than place –ity in these trees as a lone daughter to the N node (and –able as the lone daughter of Adj) or give –ityan “N” feature, we show –ity adjoined to N. This would be consistent with the analyses of category heads in Distributed Morphology, with little n replacing N in the trees, and –ity considered a root adjoined to n. This discussion will assume that the details here don’t matter (though they probably will turn out to).

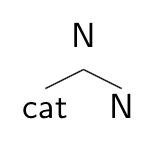

In considering probabilistic context-free phrase structure rules as part of a model of word recognition, the relevant parts of the trees above are at the top. We can ask, for treatability, whether the frequency of all nouns derived from adjectives, independent of any of the specific morphemes in the word, matter for the recognition of the word. In phrase structure rule terms, this would be the frequency of the rule N → Adj + N. For sanity, there are at least a couple different ways to think of its structure in phrase structure terms.  If sane is really a root, rather than an adjective, then it’s not clear that the top phrase structure of sanity is any different from that of cat, consisting of a root adjoined to a category head.

If sane is really a root, rather than an adjective, then it’s not clear that the top phrase structure of sanity is any different from that of cat, consisting of a root adjoined to a category head.

However, one could also ask whether the probability of a derived noun (involving a root like –ity as well as a categorizing head, sketched below) as opposed to a non-derived noun (just the stem and the category suffix, with no additional root) could make a difference in processing.

Some ways, then, in which probabilistic context-free phrase structure rules could be shown to make a difference in word recognition is if processing is affected by:

- frequency of categories (nouns vs. verbs vs. adjectives)

- frequency of derivational frames (when one category is derived from another category)

- frequency difference between non-derived categories (involving only a root and a category affix) and derived categories (involving at least an additional root tied to the category affix)

In visual lexical decision experiments, we know that by the time a participant presses a button to indicate that yes, they saw a real word as opposed to a non-word, the lexical category of the word makes a difference for reaction time above the usual frequency and form variables. In fact, as shown in Sharpe & Marantz (2017), reaction time in lexical decision can be modulated by connections between phonological/orthographic form of a word and how often that word is used as a noun or a verb. What we don’t yet know is if lexical category (by itself) or the sort of variable investigated in Sharpe & Marantz can modulate the “M170” – the response measured at 170ms after visual onset of a word stimuli in the visual word form area (VWFA) associated with morphological processing. Similarly, if we find that reaction time in lexical decision is modulated by the frequency of nouns formed from adjectives, we would still not know whether this variable is implicated specifically in morphological processing or in some later stage of word recognition within the lexical decision experimental paradigm.

However, we do know that certain probabilistic variables that don’t seem to implicate phrase structure rules do modulate visual word recognition at the M170. These include “transition probability,” which for the experiments in question was computed as the ratio of the frequency of a given stem + affix combination to the frequency of the stem in all its uses. So the transition probability from sane to –ity is computed as the ratio of the frequency of sanity to the stem frequency of sane (sane in all its derived and inflected forms). But we should investigate whether transition probability works to explain variance in the M170 because it represents something intrinsic to the storage of knowledge about words, or whether it could correlate with a set of variables related to phrase structure.

Compounds represent another class of morphologically complex words for which probabilistic phrase structure rules might be appropriate. Compound structures are subject to a great deal of cross-linguistic variation, and in work from the 1980’s, Lieber and others suggested that the phrase structure rules of a language might describe the types of compounds available in the language. So in English, rules like N → {Adj, N} + N might describe nominal compounds (green house, book store), while the lack of a compound rule V → X + V might account for the lack of productive verbal compounding. It’s not clear that the category of the non–head constituent in an English compound is categorially constrained (keep off the grass sign, eating place), and in any case the syntactic structure of compounds is probably more complicated than it seems on the surface. Nevertheless, experiments should check whether, say, the general frequency of compounds consisting of noun + noun (yielding a noun) modulates morphological processing independently of the specific nouns involved.

Patterning perhaps with compounds are structures with affixes like –ish. Derivation with –ish is productive, which might seem to put –ish with comparative –er in the extended projection of adjectives (smaller, smallish). However, –ish, like compound heads, is not really restrictive as to the category of its stem (Google-ish, up-ish), and of course also has a use as an independent word (Dating one’s ex’s roommate is so ish, according to Urban Dictionary).

In short, it’s an open and interesting question what the relevant probabilistic structural information is for processing compounds and –ish-type derivatives, but we don’t yet know how general phrase structure knowledge might be relevant.

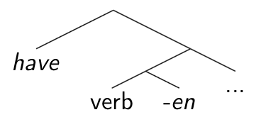

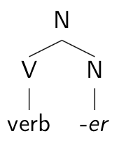

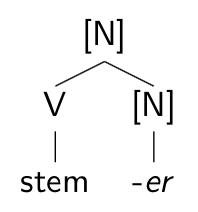

Finally, let’s return to inflection and the derivation we suggested might appear with inflection in the extended projections of lexical categories (e.g., nominalizing –er for verbs). If we treat the category of a word along its extended projection as remaining stable (e.g., Verb, for all nodes along the “spine” of the extended projection of a Verb), then the phrase structure rules for morphemes along extended projections would look something like: Verb → Verb + Tense. Note again that neither phrase structure rules nor standard selectional features are good tools for deriving the (relatively) fixed sequence of functional heads in an extended projection. But we could ask whether encoding knowledge of extended projections in phrase structure rules like Verb → Verb + Tense could aid in explaining morphological processing in some way. That is, could the processing of a tensed verb depend on the frequency of tensed verbs in the language, independently of any knowledge of the particular verb and tense at hand?

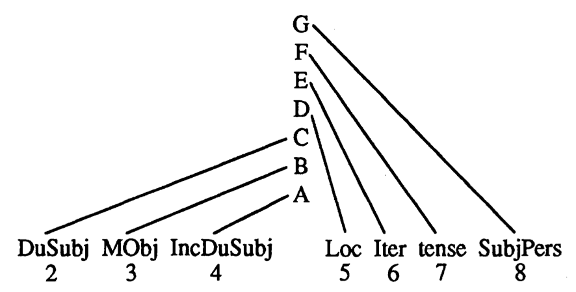

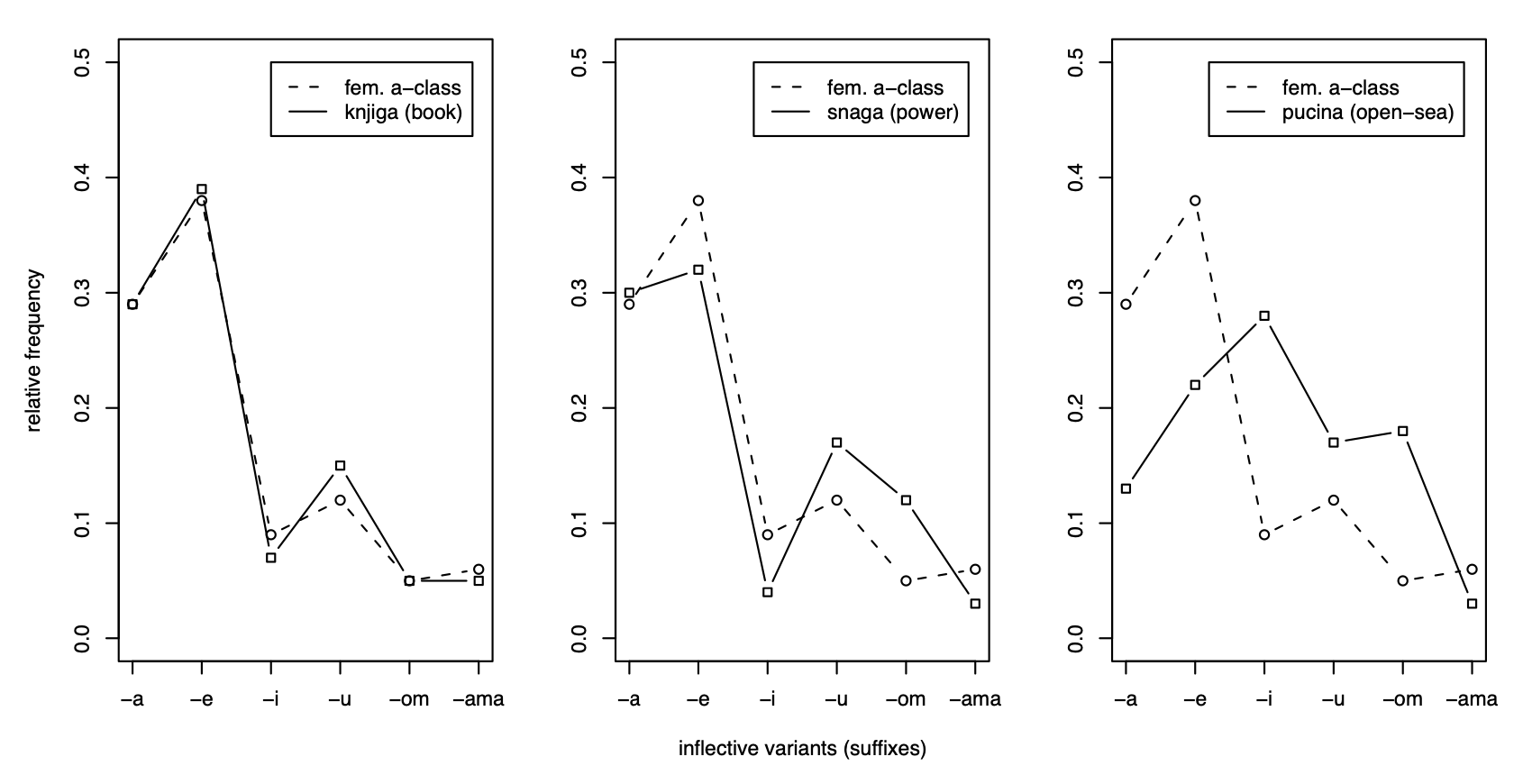

Other than phrase structure-type probabilities, what other probabilistic information about extended projections might modulate the processing of an inflected word independently of the specific morphemes in the word? In an interesting series of papers, Harald Baayen and colleagues have suggested that processing might be modulated by variables associated with probability distributions over paradigms (see, e.g., Milin et al. 2009a,b). In addition to exploring the effects on processing of what we have called transition probability (the probability of the inflected word given the stem, in one direction, or the probability of the inflected word given the affix, in the other), they propose that processing is also affected by the relative frequency of the various inflected forms of a word, computed as “paradigm entropy.” Transition probabilities and paradigm entropy are both variables associated with particular stems. Interestingly, they also employ variables involving probabilities from the language beyond the statistics of particular stems. Milin et al. (2009a) suggest that the relative entropy of the paradigm of a stem also modulates processing. Relative entropy involves a comparison of the paradigm entropy of the stem of a word with the average entropy of all the stems in the same inflectional class. The idea is information theoretic: how much additional information do you gain from identifying a specific stem (with its own paradigm entropy) once you know to which inflectional class the stem belongs? Figure 1 below from Milin et al. (2009a) shows the paradigm entropies of three Serbian nouns (knjiga, snaga, pucina) and the frequencies of the inflectional class (feminine a-class) to which they belong.

Relative entropy is a variable like the one explored in Sharpe & Marantz, which involved a comparison of the relationship between the form of a word and its usage as a noun vs. a verb with the average relationship between forms and usage across the language. What’s particularly interesting in the present context about the sort of paradigm variables identified by Milin et al. becomes clear if we recall the connection between paradigms and extended projections, and the identity between extended projections in the context of inflected words and extended projections in the context of sentences. As I suggested before, sentences in an important sense belong to verbal paradigms, which in English consist of a verb and the set of modals and auxiliaries associated with the “spine” of functional elements as summarized in Chomsky’s Tense-Modal-have-be-be-Verb sequence. If Milin et al. are on the right track, the relative entropy of these extended verbal “paradigms” should also be considered as a variable in sentence processing.

References

Milin, P., Filipović Đurđević, D., & Moscoso del Prado Martín, F. (2009a). The Simultaneous effects of inflectional paradigms and classes on lexical recognition: Evidence from Serbian. Journal of Memory of Language 60(1): 50-64.

Milin, P., Kuperman, V., Kostic, A., & Baayen, R.H. (2009b). Paradigms bit by bit: An information theoretic approach to the processing of paradigmatic structure in inflection and derivation. In Blevins, J.P. & J. Blevins, J. (eds.), Analogy in grammar: Form and acquisition, 214-252. Oxford: OUP.

Sharpe, V., & Marantz, A. (2017). Revisiting form typicality of nouns and verbs: a usage-based approach. The Mental Lexicon 12(2): 159-180.

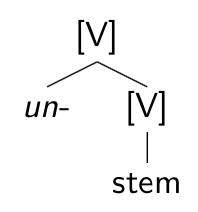

that do not change category would either not be heads (perhaps they would be “adjuncts”) or would be category-less affixes, with the category of the stem “percolating” up by default to be the category of the derived form.

that do not change category would either not be heads (perhaps they would be “adjuncts”) or would be category-less affixes, with the category of the stem “percolating” up by default to be the category of the derived form.