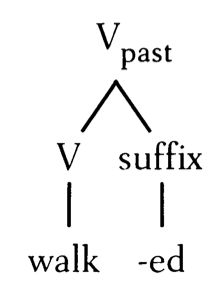

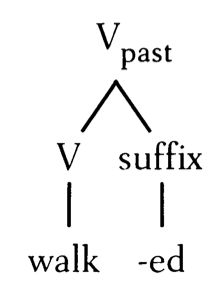

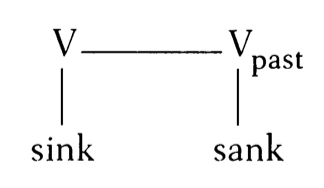

On the general line of thinking in these blog posts, a word like walked is morphologically complex because it consists of at least some representation of a stem plus a past tense feature (more specifically, a head in the extended projection of a verb). This is also true of the “irregular” word taught. Thus there is an important linguistic angle from which walked and taught are equally morphologically complex, whatever one thinks about how many phonological or syntactic pieces there are in either form.

On the general line of thinking in these blog posts, a word like walked is morphologically complex because it consists of at least some representation of a stem plus a past tense feature (more specifically, a head in the extended projection of a verb). This is also true of the “irregular” word taught. Thus there is an important linguistic angle from which walked and taught are equally morphologically complex, whatever one thinks about how many phonological or syntactic pieces there are in either form.

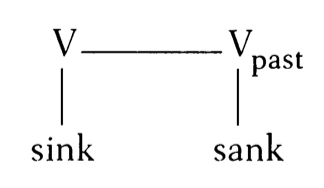

Steven Pinker, in his (1999/2015) Words and Rules work, proposes a sharp dichotomy between morphologically complex words that are constructed by a rule of grammar and thus are not stored as wholes vs. complex words that are not constructed by a rule and thus are stored as wholes. For Pinker, the E. coli of psycho-morphology is the English past tense, which he began to study (in 1988, with Alan Prince) when preparing a response to McClelland and Rumelhart’s (1987) connectionist model. The idea was that the relationship between teach and taught is a relationship between whole words (like that between cat and dog),  while the relationship between walk and walked is rule-governed, such that walked is not stored as a word and must be generated by the grammar when the word is used.

while the relationship between walk and walked is rule-governed, such that walked is not stored as a word and must be generated by the grammar when the word is used.

In point of fact, the English past tense is not a particularly good test animal for theories of morphological processing. The type of allomorphy illustrated by English inflection is limited and it confuses two potentially separable issues: stem allomorphy and affix allomorphy. For example, in the “irregular” past tense felt, we see the special fel- stem, where feel-would be expected, and the irregular –t affix, where –d would be expected (compare peeled). In canonical Indo-European languages with rich inflectional morphology, “irregular” (not completely predictable) forms of a stem can combine with regular suffixes, and unpredictable forms of suffixes can combine with regular stems. From a linguistic point of view, taught could be either a special stem form taught- with a phonologically zero past tense ending, a special stem form taugh- with a special ending –t (a wide-spread allomorph of the English past tense, but not generally predicted after stems ending in a vowel, where –d is the default), or a “portmanteau” form covering both the stem and the past tense – this last option seems to be what Pinker had in mind. Even mildly complex inflectional systems, then, exhibit a variety of types of “irregularity.” The very notion of “irregularity,” that a pattern is not predictable from the general facts of a language, implies that something needs to be learned and memorized about irregular forms. But the conflation of irregularity with stored whole forms, as in Pinker’s analysis of English irregular past tense, obscures important issues and questions for morphology and morphological processing.

A textbook case of irregular stems with regular endings occur in the Latin verb ‘to carry.’ As canonically presented in Latin dictionaries, the three “principal parts” of ‘to carry’ are ferō ‘I carry,’ tulī ‘I carried’ and the participle lātum‘carried’, with three “suppletive” stems. Crucially, each of these stems occurs with endings appropriate for the inflectional class of the stem (for contrasts like indicative vs. subjunctive and for person and number of the subject). It’s not at all obvious what the general Words and Rules approach would say about such cases, but memorization of whole words here doesn’t seem to be a plausible option. Once we sketch out a general theory of “irregularity,” the proper analysis of the English past tense should fall into line with what’s demanded by the general theory.

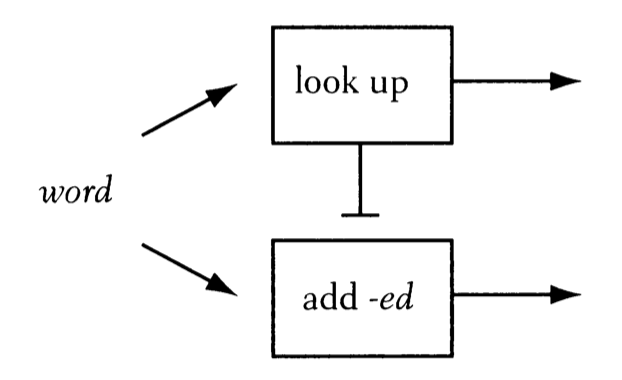

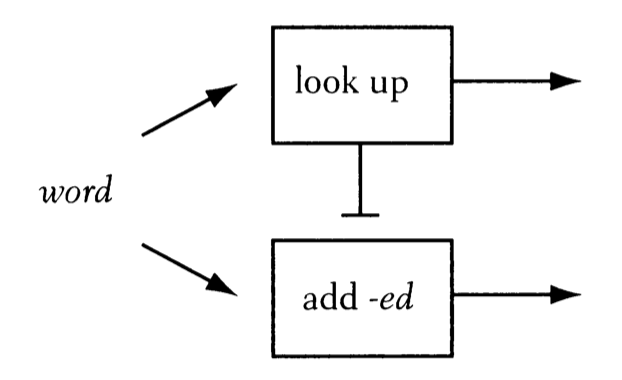

Pinker invokes an “add –ed” past tense rule when explaining his approach in general terms, but in his work he sometimes presents a more explicit account of how a grammar might generate the past tense forms in a Word and Rules universe. Here, the important concept is that a stored, special form blocks the application of a general rule.

The implementation follows the linguistics lead of Paul Kiparsky’s version of Lexical Phonology and Morphology from around 1982. At this point in time, Kiparsky’s notion was that a verb would enter into the (lexical) morphology with a tense feature. At “Level 1” in a multi-level morpho-phonology, an irregular form would spell out the verb plus the past tense feature, blocking the affixation of the regular /d/ suffix at a later level. The pièce de résistance of this theory was an account of an interesting contrast between regular and irregular plurals in compound formation. Famously, children and adults find mice-eater to be more well-formed than rats-eater. Kiparsky’s account put compound formation at a morpho-phonological “level” between irregular morphology and regular inflection, allowing irregular inflected forms to feed compound formation, but having compound formation bleed regular inflection (on an internal constituent). The phenomenon here is fascinating and worthy of the enormous literature devoted to it. However, Kiparsky’s analysis was a kind of non-starter from the beginning. The problem was that if irregular inflection occurs at Level 1 in the morpho-phonology, it should not only feed compound formation but also derivational morphology. So, someone that used to teach could be a taughter on this analysis.

To cut to the chase, the Words and Rules approach to morphology isn’t compatible with any (even mildly current) linguistic theory, and as noted above, it’s difficult to apply beyond specific examples that closely resemble the English past tense, where the irregular form may appear to be a portmanteau covering a stem and affixal features. However, Pinker has always claimed that experimental data support his approach, so it’s important to investigate whether his particular proposal about stored vs. computed words makes interesting and correct predictions about experimental outcomes. Here it’s important to distinguish data from production studies and data from word recognition.

For production, the Words and Rules framework was supposed to make two types of prediction, one for non-impaired populations and another for impaired populations. In terms of reaction time, non-impaired speakers were supposed to produce the past tense of a presented verb stem in a time that, for irregulars, correlated with the surface frequency of the past tense verb and, for regulars, correlated with the frequency of the stem. For impaired speakers, the prediction was a double dissociation: impairment to the memory systems would differentially impair irregulars over regulars, while impairment to the motor sequencing system would differentially impair regulars over irregulars. Michael Ullman took over this research project, using the English past tense as an assay for the type of impairment a particular population might be suffering (see, e.g., Ullman et al. 2005). In his declarative/procedural model, irregulars are produced as independent words, while regulars are produced by the procedural system, which is involved in motor planning and execution. However, for Ullman the story is clearly one about the specifics of production, and not about the grammatical system, as it is for Pinker. For example, his studies find that women are more likely than men to produce regular past tense forms at a speed correlated with surface frequency, which suggests that women memorize these forms, while (most/many) men do not. If Ullman were connecting his studies to the grammatical system, he would predict that women more than men would like rats-eater, for example. But his theory is about online performance rather than grammatical knowledge or use. By sticking with systems like the English past-tense, which confounds morphological affixation with phonological concatenation, Ullman can’t distinguish whether the declarative/procedural divide is about the phonological sequencing of the phonological forms of morphemes or about the concatenation of morphemes themselves.

A nice study by Sahin et al. (2009, which includes Pinker as co-author) does explore the neural mechanisms of the production of inflected forms with an eye to distinguishing phonological and morphological processing. Sahin et al. find stages in processing in the frontal lobe that are differentially sensitive to morphological structure (reflecting, say, the process “add inflection”) and phonological structure (reflecting, say, the process “add an overt suffix”), with the former preceding the latter. Interestingly, Sahin et al. found no difference between regular and irregular inflection.

In short, the conclusion from the production studies, no matter how charitable one is to Ullman’s experiments (see Embick and Marantz 2005 for a less charitable view), is that although phonological concatenation in production may distinguish between forms with overt suffixes and forms with phonologically zero affixes, no data from these studies support the Words and Rules theory when interpreted to be about morphological processing.

But what about processing in word recognition or perception? Here, it’s unclear whether there was ever any convincing support for the Words and Rules approach. Pinker and others cite a paper by Alegre and Gordon (1999) as providing evidence for the memorization vs. rule application distinction in lexical decision paradigms. However, Alegre and Gordon’s experiments and their interpretation, even if taken at face value, would hardly be the type of evidence one would want for Words and Rules. Their initial experiment finds no frequency effects for reaction time in lexical decision for regular verbs and nouns (expanding well beyond the past tense to other verb forms and to noun plurals) – neither “surface” frequency of the inflected form nor a type of base frequency (frequency of the stem across all inflections, which they call “cluster frequency”). In subsequent experiments reported in the paper, and in a reanalysis of their data from the first experiment, Alegre and Gordon claim that regularly inflected forms show surface frequency effects in lexical decision if they occur above a certain threshold frequency. If that were true (and subsequent work has shown that the generalization is incorrect), it would severely undermine Pinker’s theory. We’re not just talking about peas and toes here; “high frequency” and putatively memorized inflected forms include deputies, assessing, pretending and monuments. If the Words and Rules approach were the correct explanation of the data, we’d expect monuments-destroying to be as well-formed as monument-destroying. If we are indeed memorizing these not really so frequent inflected forms as wholes, the notion of “memorization” here must be divorced from any connection to grammatical knowledge.

However, Lignos and Gorman (2012) show that Alegre and Gordon’s results and interpretation can’t be taken at face value, pointing out a number of problems in the paper, including the reliance on frequency counts inappropriate for their study. The more robust finding is that the surface frequency effect is stronger, not weaker, in the low surface frequency range for morphologically complex words. Recent work in this area paints a complex picture of the variables modulating reaction time in lexical decision, which include both some measure related to base frequency and some measure related to surface frequency, but no current research in morphologically complex word recognition supports the key predictions of the Words and Rules framework, at least as laid out by Pinker and colleagues.

Recall that if you know the grammar of a language – if you’ve “memorized” or “learned” the rules – you have, in an important sense, memorized all the words (and all the sentences) that are analyzable or generatable by the grammar, even the ones you haven’t heard or spoken yet. That is, the “memorized” grammar generates words that you have already encountered or used in the same way it generates words that you haven’t (yet) encountered or used. In other words, when you’ve “memorized” the grammar, you’ve “memorized” both sets of words. From the standpoint of contemporary research in morphological processing, this understanding of “memorization” should replace the thinking of the Words and Rules framework, which makes speakers’ prior experience with words a crucial component of their internal representation.

However, it should be noted that Pinker’s main concern in Words and Rules was on language acquisition and the generalization of “rules” to novel forms. Recent work by Charles Yang (2016), Tim O’Donnell (2015) and others recasts the Words and Rules dichotomy between memorization vs. constructed as an issue of words following unproductive rules or generalizations, for which you have to memorize for each word that the rule or generalization applies (or memorize the output without reference to the generalization) vs. words following productive rules or generalizations, for which the output is predicted. Key data for these investigations come from wug tests of rules application to novel forms. An issue to which we will return soon is how these theories of productivity of morphological rules tie into models of morphological processing in word recognition.

References

Alegre, M., & Gordon, P. (1999). Frequency effects and the representational status of regular inflections. Journal of memory and language, 40(1), 41-61.

Embick, D., & Marantz, A. (2005). Cognitive neuroscience and the English past tense: Comments on the paper by Ullman et al. Brain and Language, 93(2), 243-247.

Kiparsky, P. (1982). From cyclic phonology to lexical phonology. The structure of phonological representations, 1, 131-175.

Lignos, C., & Gorman, K. (2012). Revisiting frequency and storage in morphological processing. In Proceedings from the Annual Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, 48(1), 447-461. Chicago Linguistic Society.

O’Donnell, T. J. (2015). Productivity and reuse in language: A theory of linguistic computation and storage. MIT Press.

Pinker, S. (1999/2015). Words and rules: The ingredients of language. Basic Books.

Pinker, S., & Prince, A. (1988). On language and connectionism: Analysis of a parallel distributed processing model of language acquisition. Cognition, 28(1-2), 73-193.

Rumelhart, D. E., & McClelland, J. L. (1987). Learning the past tenses of English verbs: Implicit rules or parallel distributed processing?. In B. MacWhinney (ed.), Mechanisms of language acquisition, 195-248. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Sahin, N. T., Pinker, S., Cash, S. S., Schomer, D., & Halgren, E. (2009). Sequential processing of lexical, grammatical, and phonological information within Broca’s area. Science, 326(5951), 445-449.

Ullman, M. T., Pancheva, R., Love, T., Yee, E., Swinney, D., & Hickok, G. (2005). Neural correlates of lexicon and grammar: Evidence from the production, reading, and judgment of inflection in aphasia. Brain and Language, 93(2), 185-238.

Yang, C. (2016). The price of linguistic productivity: How children learn to break the rules of language. MIT Press.

On the general line of thinking in these blog posts, a word like walked is morphologically complex because it consists of at least some representation of a stem plus a past tense feature (more specifically, a head in the extended projection of a verb). This is also true of the “irregular” word taught. Thus there is an important linguistic angle from which walked and taught are equally morphologically complex, whatever one thinks about how many phonological or syntactic pieces there are in either form.

On the general line of thinking in these blog posts, a word like walked is morphologically complex because it consists of at least some representation of a stem plus a past tense feature (more specifically, a head in the extended projection of a verb). This is also true of the “irregular” word taught. Thus there is an important linguistic angle from which walked and taught are equally morphologically complex, whatever one thinks about how many phonological or syntactic pieces there are in either form. while the relationship between walk and walked is rule-governed, such that walked is not stored as a word and must be generated by the grammar when the word is used.

while the relationship between walk and walked is rule-governed, such that walked is not stored as a word and must be generated by the grammar when the word is used.

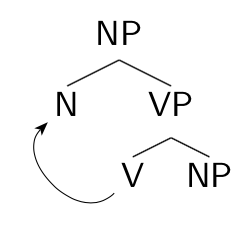

A popular account of what Grimshaw called “complex event nominalizations” (cf. John’s frequent destruction of my ego) involves postulating that these nominalizations involve a nominalizing head taking a VP complement. When the head V of the VP moves to merge with the nominalizing head, the resulting structure has the internal syntactic structure of an NP, not a VP. For example, there’s no accusative case assignment to a direct object, and certain VP-only complements like double object constructions (give John a book) and small clauses (consider John intelligent) are prohibited (*the gift of John of a book, *the consideration of John intelligent).

A popular account of what Grimshaw called “complex event nominalizations” (cf. John’s frequent destruction of my ego) involves postulating that these nominalizations involve a nominalizing head taking a VP complement. When the head V of the VP moves to merge with the nominalizing head, the resulting structure has the internal syntactic structure of an NP, not a VP. For example, there’s no accusative case assignment to a direct object, and certain VP-only complements like double object constructions (give John a book) and small clauses (consider John intelligent) are prohibited (*the gift of John of a book, *the consideration of John intelligent).

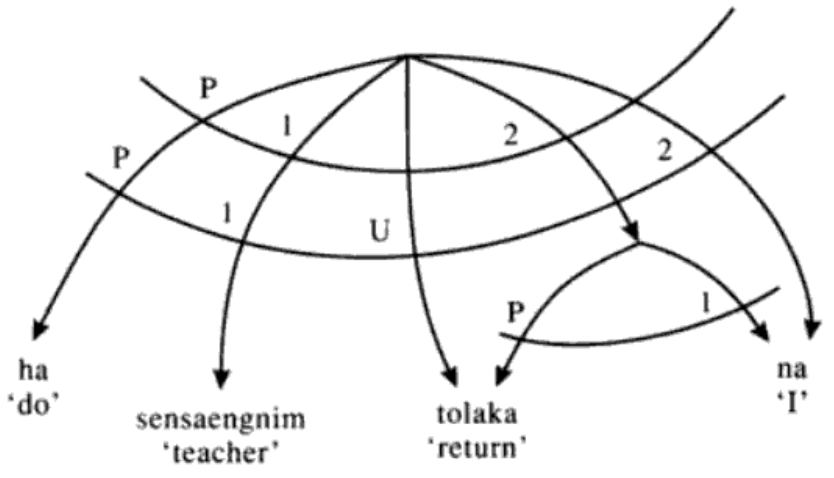

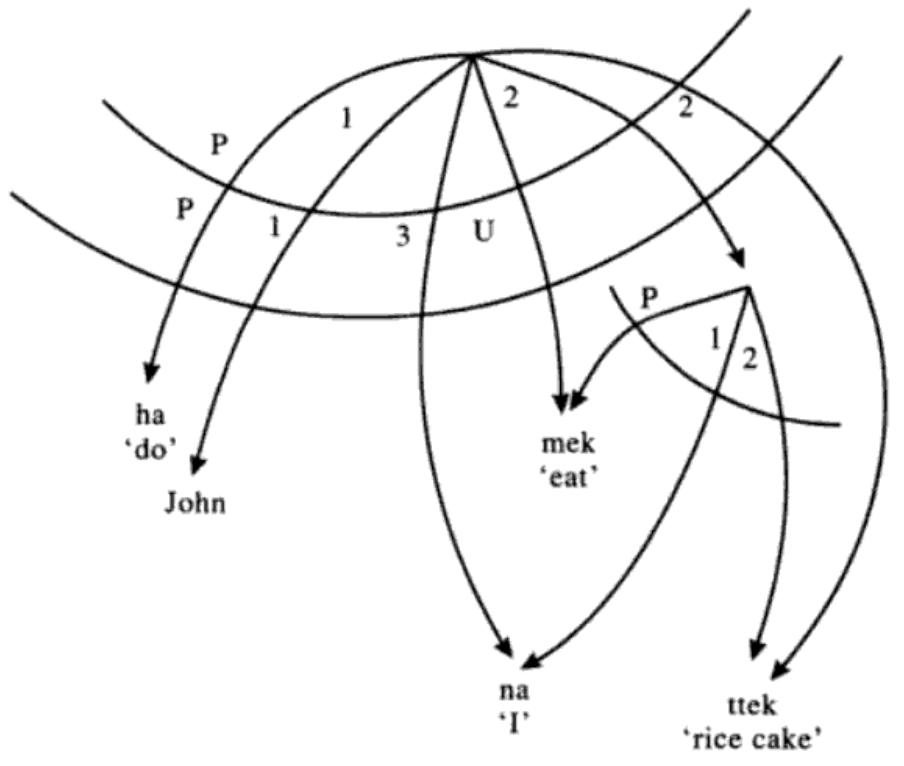

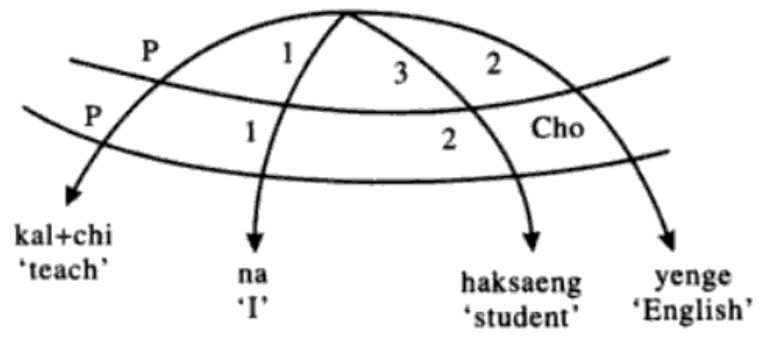

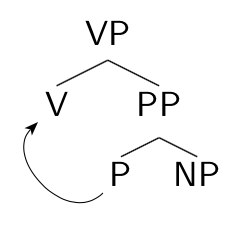

Within the Marantz (1981, 1984) framework, applicative constructions involve a PP complement to a verb, with the applicative morpheme as the head P of the PP. Morphological merger of the P head with the verb collapses the VP and PP together and puts the object of the P, the “applied object,” in a position to be the direct object of the derived applicative verb.

Within the Marantz (1981, 1984) framework, applicative constructions involve a PP complement to a verb, with the applicative morpheme as the head P of the PP. Morphological merger of the P head with the verb collapses the VP and PP together and puts the object of the P, the “applied object,” in a position to be the direct object of the derived applicative verb.