In Syntactic Structures, Chomsky (1957) provides an analysis of the English auxiliary verb system that explains both the order of auxiliary verbs, when more than one are present, and the connection between a given auxiliary and the morphological form of the auxiliary or main verb that follows. For example, progressive be follows perfect have and requires the present participle –ing suffix on the verb that follows it, as in John has been driving recklessly. Subsequent work on languages that load more “inflectional” morphology on verbs and use fewer independent auxiliary verbs has revealed that the order of tense, aspect, and modality morphology cross-linguistically generally mirrors the order of English auxiliaries: tense, modal, perfect, progressive, passive, verb (or, if these are realized as suffixes, verb, passive, progressive, perfect modal, tense). Work on the structure of verb phrases and noun phrases has revealed a set of “functional” categories (for nouns, things like number, definiteness and case) that form constituents with the noun and appear in similar hierarchies across languages.

Grimshaw (1991) was concerned with puzzles that involve the apparent optionality of these functional categories connected to nouns and verbs. For example, a verb phrase may appear only with tense, as in John sings, or it may appear with a number of auxiliaries, in which case tense appears on the top/left most auxiliary: John was/is singing, John has/had been singing, etc. If tense c-selects for a (main) verb, does it optionally also c-select for the progressive auxiliary, perfect auxiliary, etc.? The proper generalization, which was captured by Chomsky’s (1957) system in an elegant but problematic way, is that the functional categories appear in a fixed hierarchical order from the verb up (Chomsky had the auxiliaries in a fixed linear order, rather than a hierarchy, but subsequent research points to the hierarchical solution). There’s a sense in which the functional categories are optional – certainly no overt realization of aspect or “passive” is required in every English verb phrase. Yet there is also a downward selection associated with these categories. The modal auxiliaries, for example, require a bare verbal stem, while the perfect have auxiliary requires a perfect participle to head its complement, and the progressive auxiliary requires a present participle for its own complement.

Grimshaw suggested that noun, verbs, adjectives and prepositions (or postpositions) anchor the distribution of “functional” material like tense or number that appears with these words in larger phrases. To borrow her terminology, a “lexical” category (N, V, Adj, P) is associated with an “extended projection” of optional “functional” (non-lexical) heads. This fixed hierarchy of heads is projected above the structure in which the “arguments” of lexical categories, like subjects and objects, appear.

What emerges from this history of phrase structure within generative syntax since the 1950’s is an understanding of the distribution of morphemes and phrases in sentences that is not captured by standard phrase structure rules. Lexical categories are associated with an “extended projection,” the grammatical well-formedness of which is governed by a head’s demands for the features of the phrases that they combine with; for example, the perfective auxiliary wants to combine with a phrase headed by a perfect participle, and the verb rely wants to combine with a phrase headed by the preposition on. The requirements of heads are thus governed by properties related to semantic compositionality (s-selection) and not directly by subcategorization (c-selection). The “arguments” of lexical categories similarly have their distribution governed by factors of s-selection and other properties (e.g., noun phrases need case), rather than by c-selection of a particular item or by phrase structure generalizations that refer directly to category (e.g., VP → V NP, where NP is the category of the verb’s direct object).

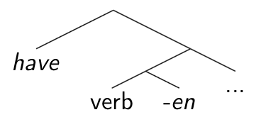

How does this discussion of constituent structure relate to morphology and the internal structure of words? First, note that the formal statement of a selectional relation between one constituent and a feature of another constituent to which it is joined in a larger structure describes a small constituent structure (phrase structure) tree. For instance, to return to an example from Syntactic Structures, the auxiliary have in English selects for a complement headed by a perfect participle (often indicated by the form of one of the allomorphs of the perfect participle suffix –en). Chomsky formalized this dependency by having have introduced along with the –en suffix, then “hopping” the –en onto the adjacent verb, whatever that verb might be (progressive be, passive be, or the main verb). In line with contemporary theories, we might formalize the selectional properties of have with the feature in (1). This corresponds to, and could be used to generate or describe, the small tree in (1). We can suppose that the “perfect participle” features of –en are visible on the verb phrase node that contains verb-en.

(1) have : [ __ [ verb+en … ] ]

Extrapolating from this example, we can note that by combining various mini-trees corresponding to selectional features, one can generate constituent structure trees for whole sentences. That is, sentence structure to some extent can be seen as a projection of selectional features.

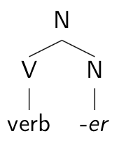

Here we can see the connection between the structure of sentences and the internal structure of words. It is standard practice in generative grammar to encode the distributional properties of affixes in selectional features. For example, the suffix –er can attach to verbs to create agentive or instrumental nouns, a property encoded in the selectional feature in (2) with its corresponding mini-tree.

(2) –er : [N verb __ ]

The careful reader may notice an odd fact about the selectional feature (4): –er, of category N, appears to c-select for the category V. Yet in our discussion of lexical categories above in the phrasal domain, we noted that nouns, verbs and adjectives don’t generally c-select for their complements; rather, lexical categories “project” an “extended projection” of “functional” heads, and s-select for complements.

The term “derivational morphology” can be used to refer to affixes that appear to determine, and thus often appear to change, the category of the stems to which they attach. Derivational affixes in English fall into at least two (partially overlapping) categories: (i) those that are widely productive and don’t specify (beyond a category specification) a set of stems or affixes to which they like to attach, and (ii) those that are non- or semi-productive and only attach to a particular set of stems and affixes. Agentive/instrumental –er is a prime example of the first set, attaching to any verb, with the well-formedness of the result a function of the semantics of the combination (e.g., seemer is odd). The nominalizer –ity is of the second sort, creating nouns from a list of stems, some of which are bound roots (e.g., am-ity), and a set of adjectives ending specifically in the suffixes –al and –able. For this second set of derivational affixes, we can say that they s-select for their complement (-ity s-selects for a “property”) and further select for a specific set of morphemes, in the same way that, e.g., depend selects for on.

But for –er and affixes that productively attach to a lexical category of stems like verbs, we do seem to have some form of c-selection: the affixes seem to select for the category of the stems they attach to. But suppose this is upside-down. Suppose we can say that being a verb means that you can appear with –er. This is very similar to saying that the form verb-er can be projected up from the verb, in the same way that (tensed) verb-s and verb-ed are constructed. That is, –ercan be seen as part of the extended projection of a verb.

Extended projections are frequently analyzed as morphological paradigms when the functional material of the extended projection is realized as affixes on the head. By performing an extended projection and realizing the functional material morphophonologically, one fills out the paradigm of inflected forms of the head. On the proposed view that productive derivational morphology associated with categories of stems involves the extended projections of the stems themselves, forms in –er, for example, would then be part of the paradigm of verbs. (This discussion echoes Shigeru Miyagawa’s (1980) treatment of Japanese causatives in his dissertation.) I’ll fill in the details of this proposal, as well as explain the contrast that emerges between the two types of derivation (productive-paradigmatic vs. semi-productive-selectional), in a later post.

Finally, remember that extended projections can be phrasal. That is, the structure of an English sentence, with its possible auxiliary verbs and other material on top of the inflected main verb, is the extended projection of the verb that heads the verb phrase in the sentence. If we view the paradigms of inflected verbs and nouns as generated from the extended projections of their stems, we can view sentences in languages like English as paradigmatic – cells in the paradigm of the head verb generated via the extended projection of that verb. When we look at phonological words in agglutinative languages like Yup’ik Eskimo, we see that these words (i) can stand alone as sentences translated into full phrasal sentences in English and (ii) have been analyzed as part of the enormous paradigm of forms associated with the head verbal root of the word. These types of examples point directly to the connection between parsing words and parsing sentences.

References

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic Structures. Walter de Gruyter.

Grimshaw, J. (1991). Extended projection. Brandeis University: Ms. (Also appeared in Grimshaw, J. (2005). Words and Structure. Stanford: CSLI).

Miyagawa, S. (1980). Complex verbs and the lexicon. University of Arizona: PhD dissertation.

Can I ask for a clarification on the terminology you’re using? You seem to be using “c-selection” to refer to any instance in which the selector selects for an entire category (e.g. “my complement should be a verb phrase”), and “s-selection” for instances in which the selector selects for a narrower set of members of that category. Is that correct?

If it is, I must say that it confuses me, on two fronts. First, calling the latter “s-selection” (and in a couple of places in the post, you explicitly refer to this as “semantic composition”) suggests that it is not a sui generis syntactic requirement. I.e., it can be subsumed under the requirements of semantic composition. This strikes me as empirically incorrect: as many L2 speakers of English will attest, there is no way to reason from the meaning of a verb like _rely_ to whether it takes an _on_-phrase or, as it does in many other languages, a _from_-phrase. The same is true, writ much larger, in the domain of extended projections. As has been noted by others, there’s actually no *semantic* reason as such for why clausal structure involves an “argument domain” (vP area), from which arguments then move into a “tense domain” (TP/middlefield area), and from there into a “discourse domain” (CP area), as opposed to these three domains being arranged in some other order (e.g. generate arguments in a discourse domain according to their discourse roles, move them through a tense domain, and finally, land them in thematic positions). In many semantic treatments, the contributions of these different domains end up related to one another via conjunction (certainly, when it comes to the semantic contributions of the argument domain on the one hand, and the tense domain on the other). And since conjunction is commutative, I don’t see how semantics is going to tell you that TP is above vP rather than the other way around.

Second, if one subscribes to Bare Phrase Structure, there aren’t really a privileged set of “category features” that set them apart from other features. So to the extent that _put_ selects any old PP as its locative argument (which, I take it, you would characterize as “c-selection”), but _rely_ selects an _on_-phrase as its argument (“s-selection”), they both just amount to selection for a feature.

(Side note: I imagine that from the perspective of a true DMer, _on_ has no features that distinguish it from _from_, as they are both just instances of ROOT embedded in the functional structure that creates a PP. Phrased this way, my point on s-selection of _on_/_from_ in the earlier paragraph can be recast as a reason to doubt such an approach to the difference between _on_ and _from_.)

By the way, I love the point about Yup’ik. I remember asking Michelle Yuan a version of this question: if we ignore orthography, what is it exactly that makes Inuktitut “polysynthetic” but English “not polysynthetic”? (I’m not saying there’s no coherent answer to this question, but it is a lot less obvious than it might appear at first glance.)

Thanks,

– Omer

Sorry for the possible unclarity in my post. I’m not proposing a 2-way distinction between s-selection and c-selection but a 3-way distinction: s-selection, c-selection, and feature selection, which I didn’t provide a name for but which is, I believe, what most people mean by default these days when they talk about heads selecting for things.

So you’re absolutely correct. I meant to say that the selection for “on” by “rely” is not s-selection but feature selection. Moreover, I meant to say that, as far as I knew, there was no real “explanation” for the order of heads in an extended projection — not obviously semantic in any case, although the usual intuition is that the order has something to do with scope. So the order of heads in an extended projection wasn’t supposed to fall under any of the 3 categories of “selection” in the story I was outlining.

And you’ve also put your finger on something I thought I was saying, but perhaps didn’t highlight: As you point out, a category feature like “n (or N)” and “v” are, in many versions of current theories, just like other features (e.g., whatever feature perfect participles have that makes them “perfect”). So it’s an observation, begging a theory of lexical categories, that (particular) nouns, verbs, and adjectives don’t c-select for the category of their complements, while they do feature select for things (as in “rely” feature-selecting for “on” to head its PP complement). Oh, and you could be right — the selection for “on” COULD be the selection for a root. In derivational morphology (see future posts), at the moment it does seem as if affixes select for roots (e.g., -ity selects for -al and -able).

So, I’m in entire agreement (I think) with your critiques. Do you have some suggestions for terminology we could use to make the (possible) distinctions among different types of “selection” clear? The c-selection vs. s-selection contrast is historically rooted. We could interpret c-selection to mean “feature selection,” and raise the question of whether selection for lexical category, among the various possible selected features, is a special form of c-selection.

Thanks for your reply. This helps clarify a lot for me.

I don’t quite know about what to do with terminology. On my own and with my students, I have been using “s-selection” to mean “selection that can ultimately be reduced to semantic composition (and therefore is not syntactic at all), and “c-selection” for selection that is syntactic. This suggests that either there is just one kind of morphosyntactic selection, or at least that if there are different kinds, they form a natural class such that “c-selection” can pick out that class. That is a substantive hypothesis, of course. Fwiw, I lean towards the view that it’s all one thing, transiting through the Bare Phrase Structure assumption that category features are just features.

Merchant (2019, TLR) revives Pesetsky’s (1991) term “l(exical)-selection” which the latter used to refer to those instances where a selector selects for something smaller than a category, up to and including selection for a particular item. This codifies the assumption that there was something natural about selection for categories and something special about selection for any smaller set, a view which as just noted, may not hold water anymore. But since the c- in c-selection invokes “category”, it would indeed be weird to use c-selection to refer to the other stuff (which falls under Pesetsky’s l-selection) *unless* one thought that it was just one thing.

Sorry, I don’t think this has all been that helpful, more of me talking myself through how I understand the terms. Oh well…

I’m definitely looking forward to hearing more about the difference between productive and semi-productive derivational affixes.

The notion of a derivational paradigm has been proposed from time to time in a variety of frameworks and approaches, even though it never really ‘took off’, right? There was a relatively recent special issue of Morphology on this: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11525-019-09344-3

Where are we now on how the optionality of extended projections are modeled in the grammar? (Assuming we don’t adopt the Cinquean perspective that everything is always there, whether inert or not.) Peter Svenonius has recent work modeling extended projections as finite state machines, and David Adger’s ‘self-merge and label’ system does something similar. But where are we in a more mainstream ‘merge and project’ system? Is it all semantic compositionality? Martina Wiltscko’s Universal Spine Hypothesis is interesting in this regard, in that it is (I hope I am getting this right) a kind of underspecified semantic compositionality. For example, you have to anchor an event to a speech event, but you can in principle use time or location to do that. The position of “Tense” in English and other languages is a consequence of what it does, but other things could in principle have done what Tense does. But it is not clear to me if the entirety of language-specific or universal extended projection hierarchies can be modeled in this way.

Thanks, Jim, for the references. Note that the novelty here is not in suggesting that derivational morphology could be paradigmatic but in saying that only a particular subset of derivational morphology should be considered paradigmatic.