| About the Show | Events | Installation Views | Show Materials |

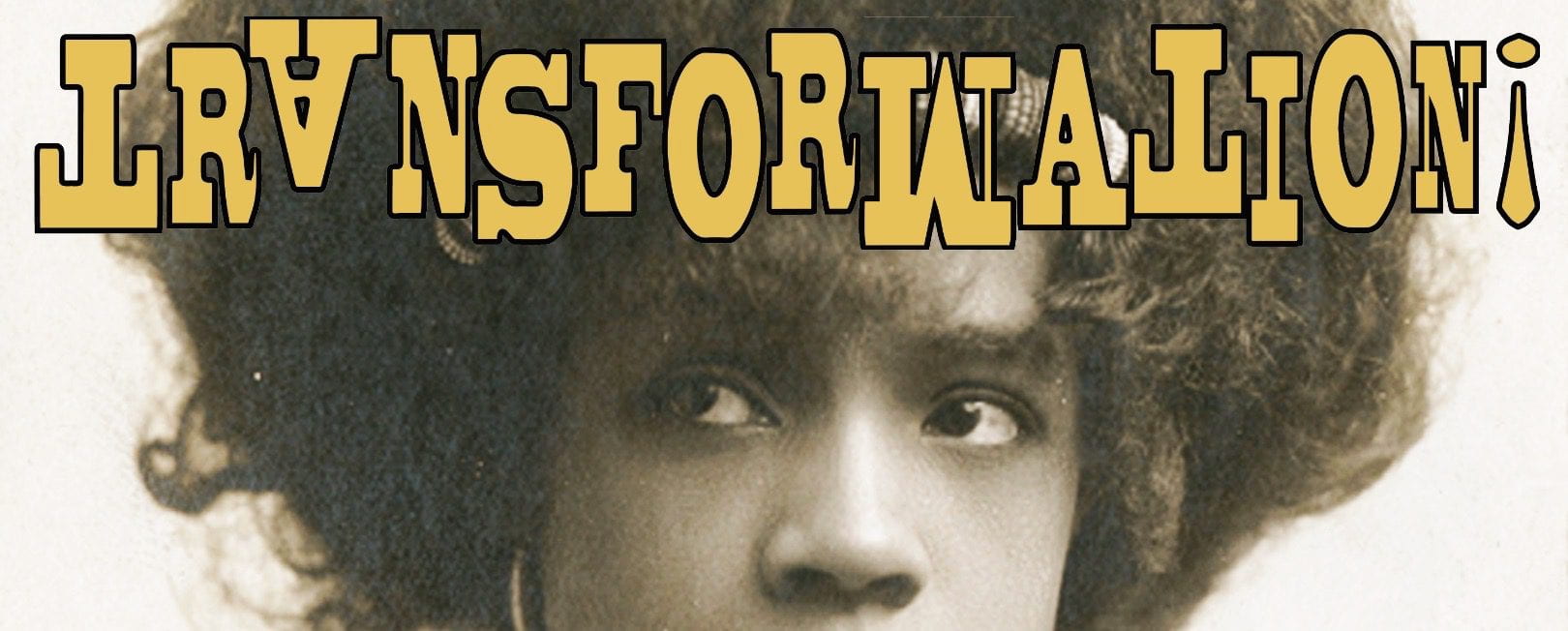

African American Theater 1821-1921 and Beyond

January 31 – March 18, 2022

Curated by Cheyenne Bryant, Jasmine Buckley, Michael Dinwiddie, Keith Miller, and Gabriela Perez

Curator’s Statement

In 1821, at the intersection of Mercer and Bleecker streets, a retired West Indian steward named William Brown opened the African Grove Theater, the first known Black theater in the United States. Although it was only open for two years, it offered a vision of what a national theater could be in the newly formed country. A century later, in 1921, Shuffle Along became the first all-Black hit Broadway show, introducing modes of song and dance that revolutionized musical theater. Between the opening of the African Grove Theater and the last performance of Shuffle Along, African American actors reshaped the American stage. Transformation! is an exploration of some of the key moments, figures, and places of that turbulent period.

As a reflection of the ongoing struggles for emancipation, 1821–1921 was filled with performers who challenged what was possible on the stage and in the public imagination through complex performative gestures. Minstrel shows, particularly those performed by Black Americans in blackface, took place alongside great feats of talent and perseverance in which performers overcame dehumanizing categorization and racist hurdles. Along the way, imaginative responses from the performers were reflective not only of the United States as it was, but, more importantly, as it could be.

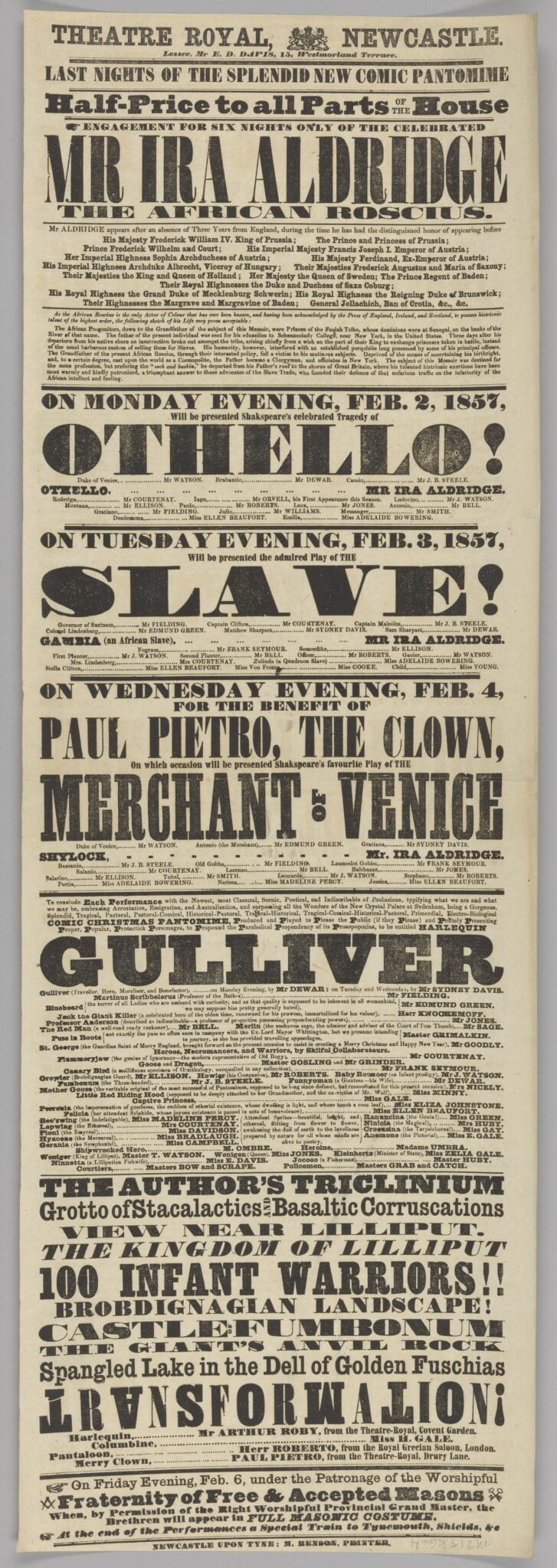

Transformation! is divided into several sections which look at the history of Black theater, beginning with the founding of The African Grove Theater—which opened six years before the abolition of slavery in New York State and almost forty years before the start of the Civil War and moving on to consider Black theatrical traditions including minstrelsy and blackface, all the while honoring celebrated performers and shows that defined and redefined the period. This section includes images and posters of the great Ira Aldridge, who began his professional career on the African Grove’s stage and was the first Black American international theater star. The exhibition goes on to look at minstrelsy, cakewalk, and blackface, which made a burlesque of Black musical traditions while also providing African American actors and musicians with new opportunities.

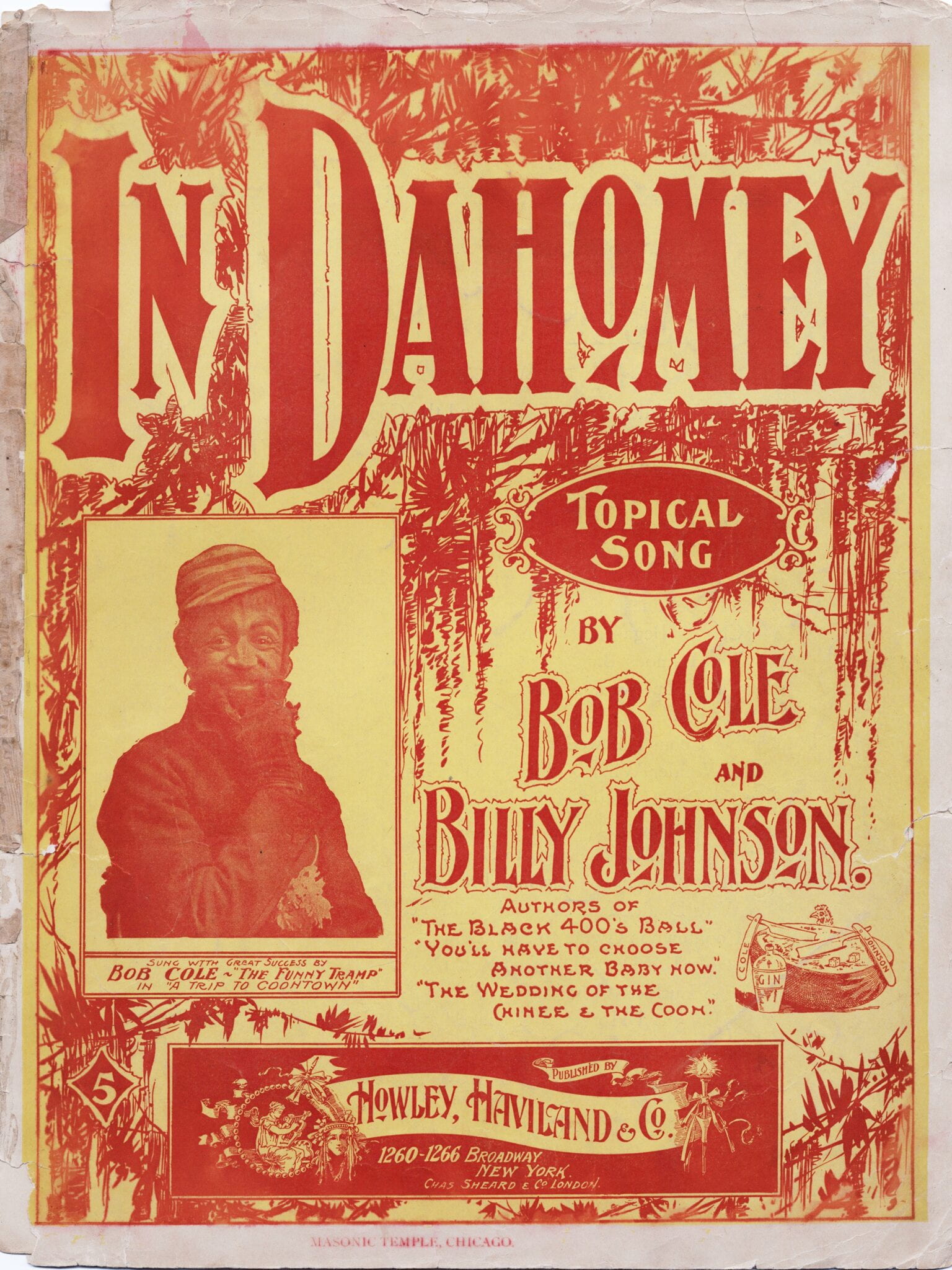

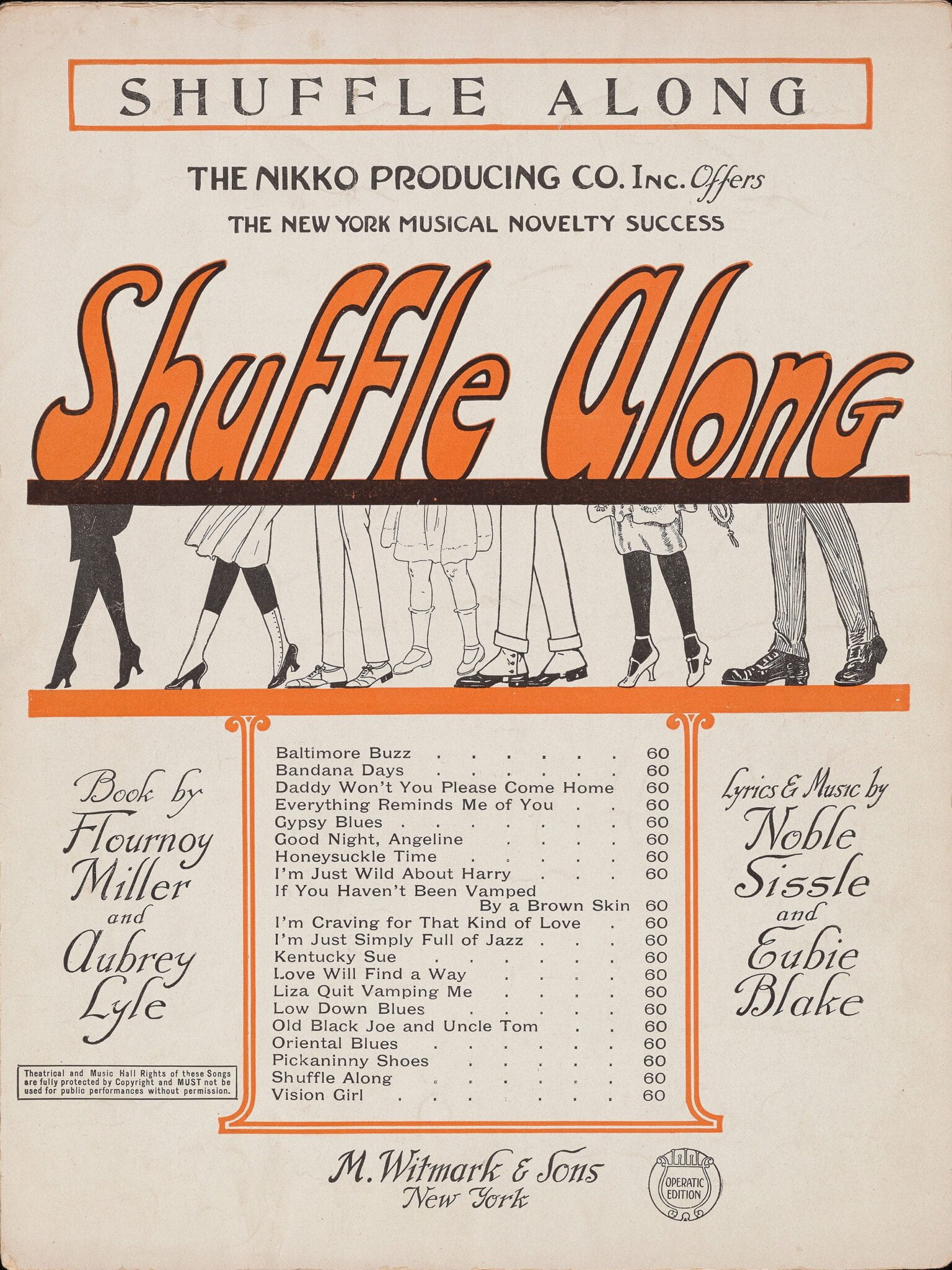

Women played a central role in the movement away from minstrelsy and blackface. The Hyers Sisters, Sissieretta Jones, Aida Overton Walker and others challenged racial and gender stereotypes and were central to the theater’s progress as it worked through the stages of becoming and creating a space for original Black voices. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these voices were becoming known throughout the country and in Europe; so, too, the opportunities for expression were broadened by groups including Cole and Johnson and Williams and Walker. In 1903, the musical In Dahomey, featuring music by Will Marion Cook and lyrics by Paul Laurence Dunbar, became the first Broadway musical written and starring a Black cast. And finally, in 1921, Shuffle Along opened in the northern edge of the so-called Great White Way. With music by Eubie Blake and lyrics by Noble Sissle, Shuffle Along drew people from the heart of Broadway, making a theatrical splash. It is a great privilege for us to present Transformation! only a few blocks north of the former site of The African Grove Theater.

MORE On this Page: Minstrelsy and Blackface • Racial Terms • African Grove: Background • Legacy • Ira Aldridge • Minstrelsy • Black Skin, Blackface, Whiteface • Cakewalk • Some Minstrel Troupes • Williams and Walker • Bert Williams • Aida Overton Walker • In Dahomey • Shuffle Along

Minstrelsy and Blackface in Transformation!

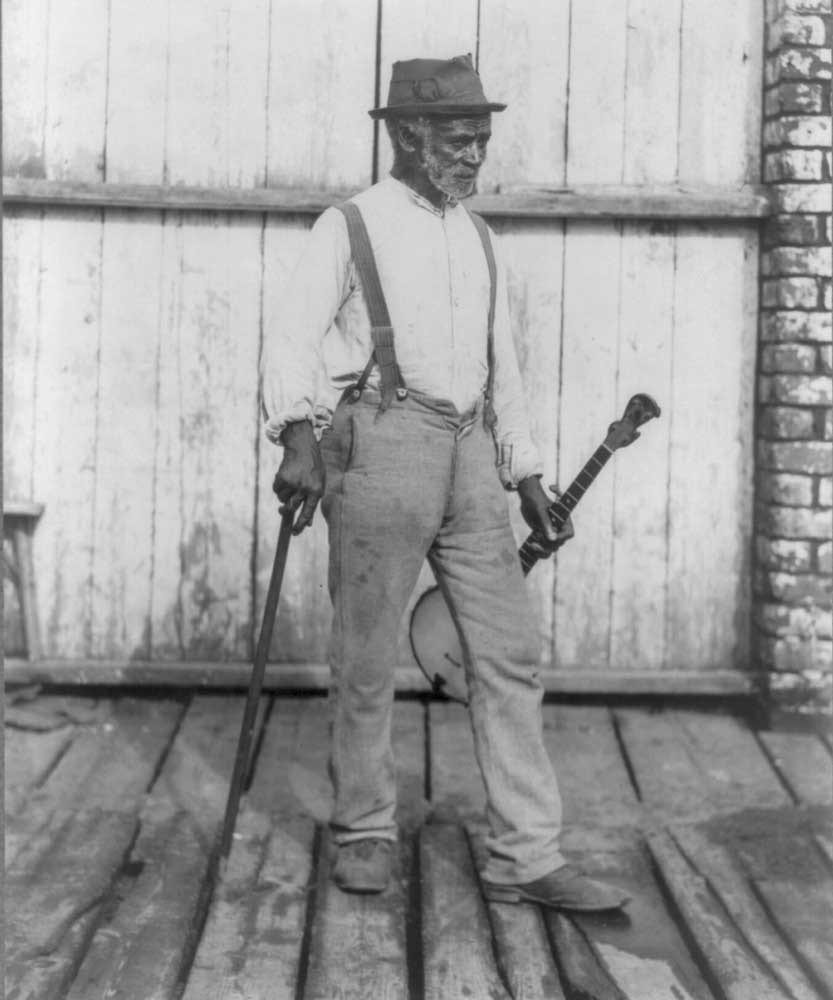

Published c1905.- Photo copyrighted by V.G. Schreck, Savannah, Ga. Courtesy Library of Congress

In Transformation!, we observe the realities of our history with an awareness of its violent legacies and its damaging manifestations in the present day, as well as the responses of individual performers to historic events and occurrences. Our hope is not only to change how we think of the history of theater, but also, and perhaps just as importantly, to investigate how we can create a space for rethinking these histories. The images of minstrelsy shown here are manifestations of racist perceptions that are still being challenged today. If some moments, images, and acts are repulsive, we have tried to place them within a continuum. For many of these artists, from William Brown to Madame Sissieretta Jones, being recognized for their achievements within an anti-Black environment was a sign that their talents were original and undeniable, even in the face of racism.

We have included racist imagery, particularly within the section looking at minstrelsy, because it is part of the theatrical and musical tradition. American music and theater during this period was full of mockery and derision of Black culture; as such, one cannot write the history of American theater or American music without keeping in mind how central Black theater and music were to its development. Minstrel performances challenge the solidity of identity and affirm alternative possibilities of becoming, especially, as theater historian Marvin McAllister points out, in the case of “stage Europeans,” or whiteface. On the stage of The African Grove Theater and in the traveling musical In Dahomey, viewers saw dynamic fluctuations in how Blackness was and could be performed, in what could be considered a precursor to contemporary code switching.

A Note on Racial Terms

Historical documents that examine and tell the story of American cultural life are replete with words and images that deny dignity to people of African descent. While antiquated terms such as “colored” and “negro” continue to command some usage in the current era, more vicious terms such as “coon” and “darkie” have fallen out of favor. The “n-word,” which still conjures up generational dissonance, has regained currency with a modified pronunciation in defiance of its oppressive history. Wherever possible, Transformation! will use the terms “Black” and “African American” and capitalize the word “Negro” when it appears in any quotes. Much of our material culture has reified pejorative racial terms, and we have done our best to attend to our audience’s complex—and complicated—relationship to racialized naming and categorization.

African Grove: Background

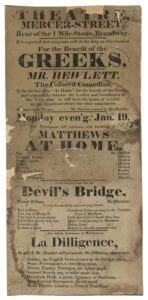

In 1816, retired West Indian steamship steward William Brown bought a house on Thomas Street, where he hosted a variety of performances on Sunday afternoons specifically for African American audiences. In 1821, Brown moved to a new house on the corner of Mercer and Bleecker and converted the second floor into a 300-seat theater which he named The African Grove Theater. Founded six years before the state of New York abolished slavery, The African Grove was an important space for expression of Black talent and creativity in New York City. The theater moved various times and the venues hosted diverse performances including ballets, musical medleys, comedies, Shakespearean performances, and even an original play written by Brown himself, The Drama of King Shotaway. In 1823, the theater was shut down by police, partly due to the rowdiness of the white crowds, though some sources claim financial instability was an additional reason for closure. There is no record of activity for the African Grove Theater after 1823.

African Grove: Legacy

According to theater historian Marvin McAllister, The African Grove Theatre “cultivated an inclusive, intercultural, multicultural, and triracial national imaginary. Confronted with the ‘twoness’ of being both American and ‘Negro’ in the United States, [William] Brown demonstrated that African Americans did not have to privilege one cultural identity at the expense of the other.” With the first integrated acting company and audiences composed of all races, the African Grove was a radical alternative to other American theaters of its time. For Brown and his collaborators, the theater was a space of possibility and becoming. Through the incorporation of Shakespearean performances, popular songs, original texts, and folk favorites, it demonstrated the range of Black subjectivities and creative expression while offering the possibility of a truly populist and popular national theater.

Ira Aldridge (1807–1867)

Ira Aldridge was one of the most distinguished and celebrated actors of his time. He is most commonly recognized as a preeminent Shakespearean tragedian, playing the likes of Othello, King Lear, and Richard III. Aldridge made his professional debut at the African Grove Theater in 1822, performing the part of Rolla in the play Pizarro alongside William Brown and James Hewlett. As the African Grove and Aldridge himself faced the brutality of rival white theater companies and disruptive audiences and mobs, he emigrated to England in hopes of finding better opportunities. Despite the scrutiny he encountered in the United States, Aldridge reached a considerable level of success overseas—later finding acclaim in France, Germany, Poland, and Russia—and became the first African American actor to establish himself professionally in Europe. Throughout his career, Aldridge took an active stance against slavery, pursuing roles based in abolitionist rhetoric and passionately speaking to audiences about racial injustice. In 1867, during what would be his final tour of Europe, Aldridge passed away in Poland.

Minstrelsy and Its Origins

“Ethiopian minstrelsy as a form of theatrical entertainment in the United States began to emerge during the 1820s and reached its zenith during the years 1840s–1880s. The first half of the period was dominated by whites, who blackened their faces with burnt cork and took to the stage to impersonate the rural slave and his free urban counterpart. In 1867, the first permanent all-black minstrel troupe was organized, and from that time on black minstrels became as common as white minstrels had been in the earlier part of the century. The black troupes maintained the same traditions as the whites, blackface and all.” —Eileen Southern, Inside the Minstrel Mask: Readings in Nineteenth Century Blackface Minstrelsy (Wesleyan University Press, 1996)

Black Skin, Blackface, Whiteface

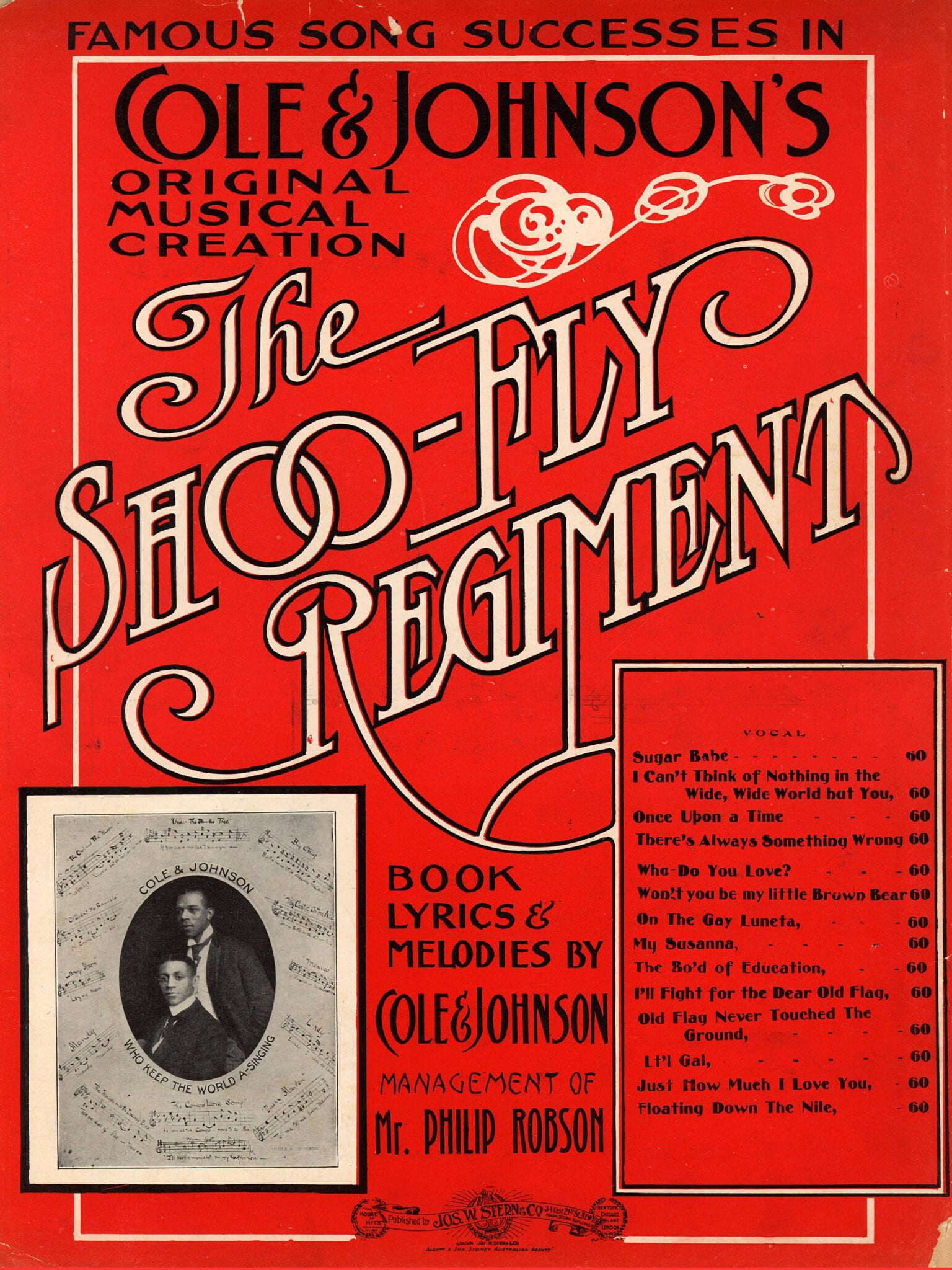

Bob Cole (1868–1911) was an African American composer, actor, playwright, stage producer, and director. In 1894, he formed the All Stock Theatre Company. According to James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan, Cole created the first school for Blacks to offer dramatic training and professional theater experience. Cole wrote, “We are going to have our own shows . . . We are going to write them ourselves, we are going to have our own stage manager, our own orchestra leader and our own manager out front to count up. No divided houses—our race must be seated from the boxes back.” In 1898, he collaborated with Billy Johnson to create A Trip to Coontown, the first musical entirely created and owned by Black showmen. Instead of performing in minstrel shows solely in blackface, Cole also donned whiteface and created the tramp character Willie Wayside. Cole’s musical comedies The Red Moon and The Shoo-Fly Regiment, created with brothers J. Rosamond and James Weldon Johnson, portrayed positive depictions of African American women and men on stage. The 1911 obituary for Bob Cole in the Black newspaper The New York Age described him as “the most versatile and gifted colored artist on the stage,” noting that “his dominant thought was to elevate the race to which he belonged.”

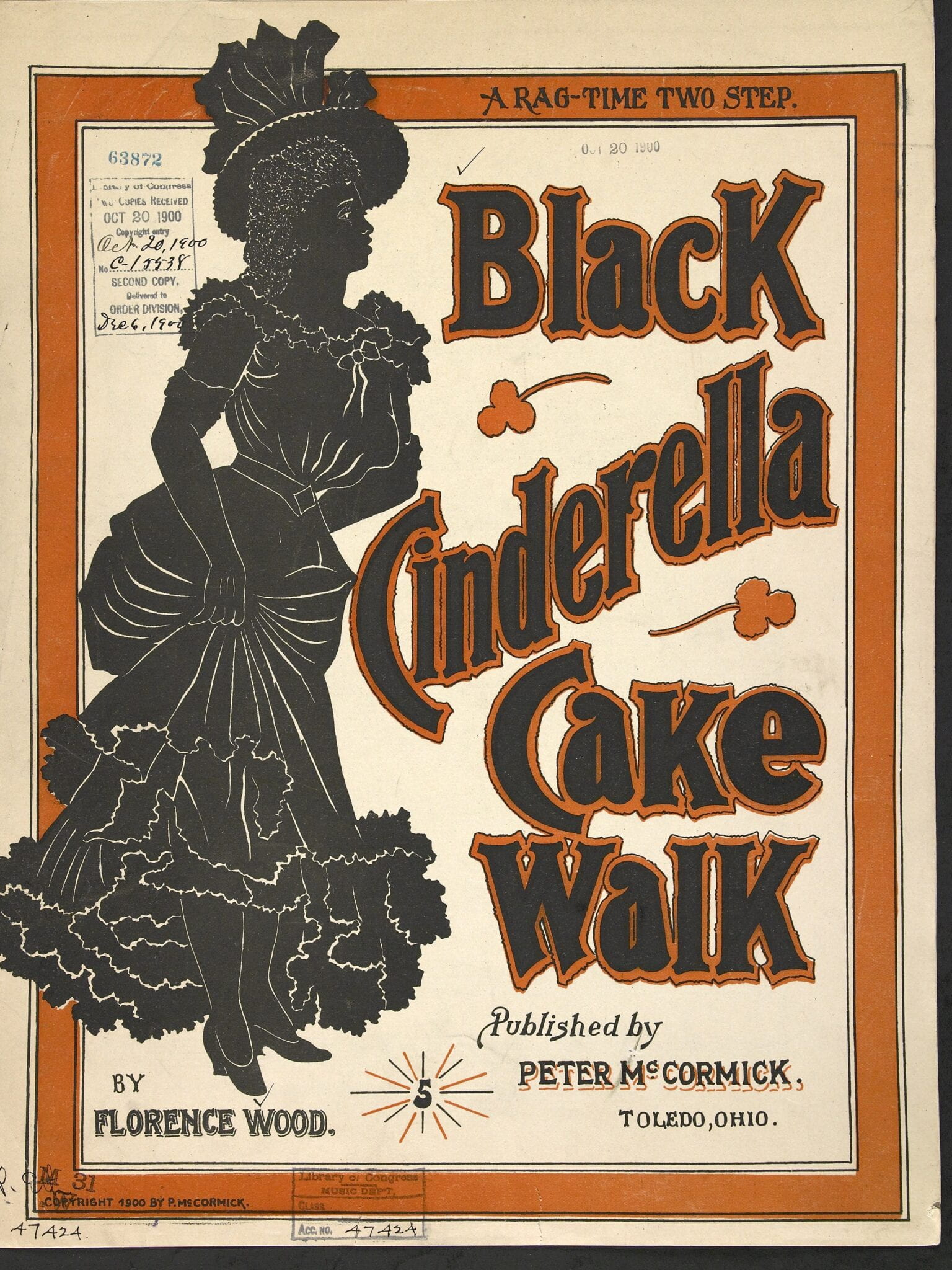

Cakewalk

The cakewalk is an African American dance that originated on Southern plantations and further developed in emancipated communities after slavery was abolished. Cakewalking contests were held at special Sunday lunches and during Christmas holidays, and served as one of the very few instances wherein the enslaved people were allowed to gather recreationally on plantation grounds. Couples would dance in a procession and the winners would “take the cake.” Imitating the ballroom promenades and waltzes of the White slave owners to a cartoonish degree, the dancers combined these seemingly mocking portrayals with traditional African moves in order to create a new and innovative African American dance of both celebration and resistance.

The dance’s satirical edge went largely unnoticed by slaveholders. While white Americans belittled the dance and those who created it, theater historian Marvin McAllister proposes that the cakewalk, as well as other whiteface spectacles performed by African Americans, were “less about ridiculing whiteness and more about showcasing black style, forging communal identity, asserting representational freedom, and training American Negroes for emancipation.”

Some Famous Minstrel Troupes

Original Georgia Minstrels – Formed in 1865, the Georgia Minstrels were among the first popular African American blackface minstrel troupes. Founded and managed by W.H. Lee, a white man, the group was made up of 15 formerly enslaved men originally from Macon, Georgia. Soon thereafter, the troupe came under the management of Sam Hague, a white minstrel performer. As Hague’s Georgia Minstrels continued to tour the United States to great acclaim, other minstrel troupes began calling themselves Georgia Minstrels as well Among them was Hick’s Georgia Minstrels, and Charles B. Hicks, its manager and namesake, would go on to become one of the most successful African American managers of a minstrel group and the first black man to own and manage a troupe of his own.

Black Patti Troubadours – Started in 1896, the Black Patti Troubadours continuously toured the country until 1916. The group was named after its founder, Sissieretta Jones, who was dubbed the “Black Patti” by a critic who compared her operatic talents to those of Adelina Patti, a renowned white singer of the time. The group’s repertoire included blackface minstrel songs and “coon” songs and incorporated performances by comedians and acrobats. Sissieretta Jones herself performed exclusively in the operatic sections, which over the years expanded to include scenery and costumes.

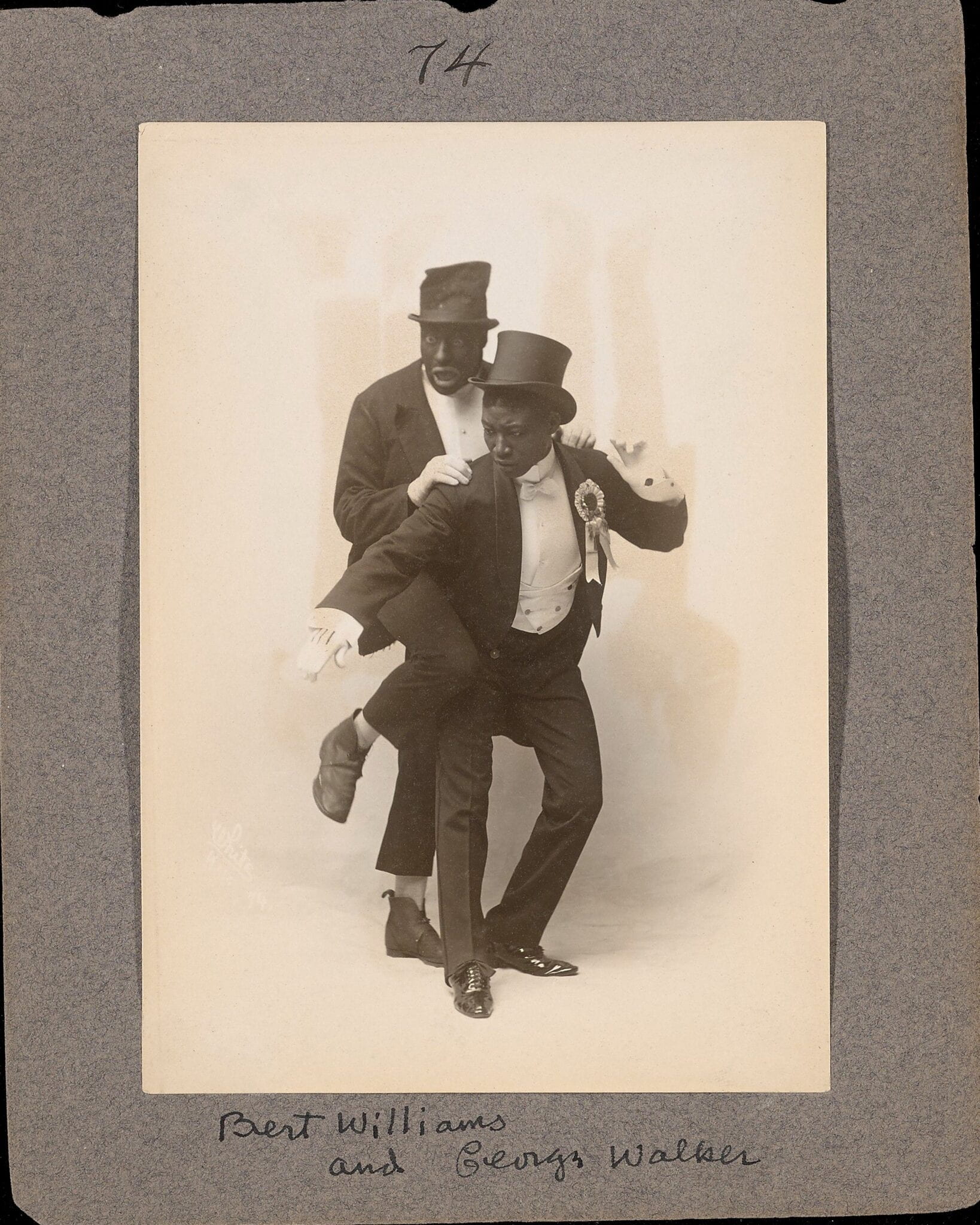

Williams and Walker

Bert Williams (1874–1922) and George Walker (1873–1911) were pioneering musicians, dancers, producers and storytellers. At the height of their collaboration they were arguably the most important comedians of the American stage. They began working together in 1893 in San Francisco and toured in the then popular traveling minstrel circuit, early on billing themselves as the “Two Real Coons.” During this time the vast majority of minstrels performing in blackface were white men. In the hands of white entertainers, a buffoonish, derogatory, and violent image of Black life was projected on stage. As a Black comedian, Bert Williams’ use of blackface subverted such caricatures. According to historian David Suisman, their “imitation of white comedians in blackface caricatured the idea of blackface itself. What could better symbolize the artifice of the minstrel characters than a black man blacking up to play himself?”

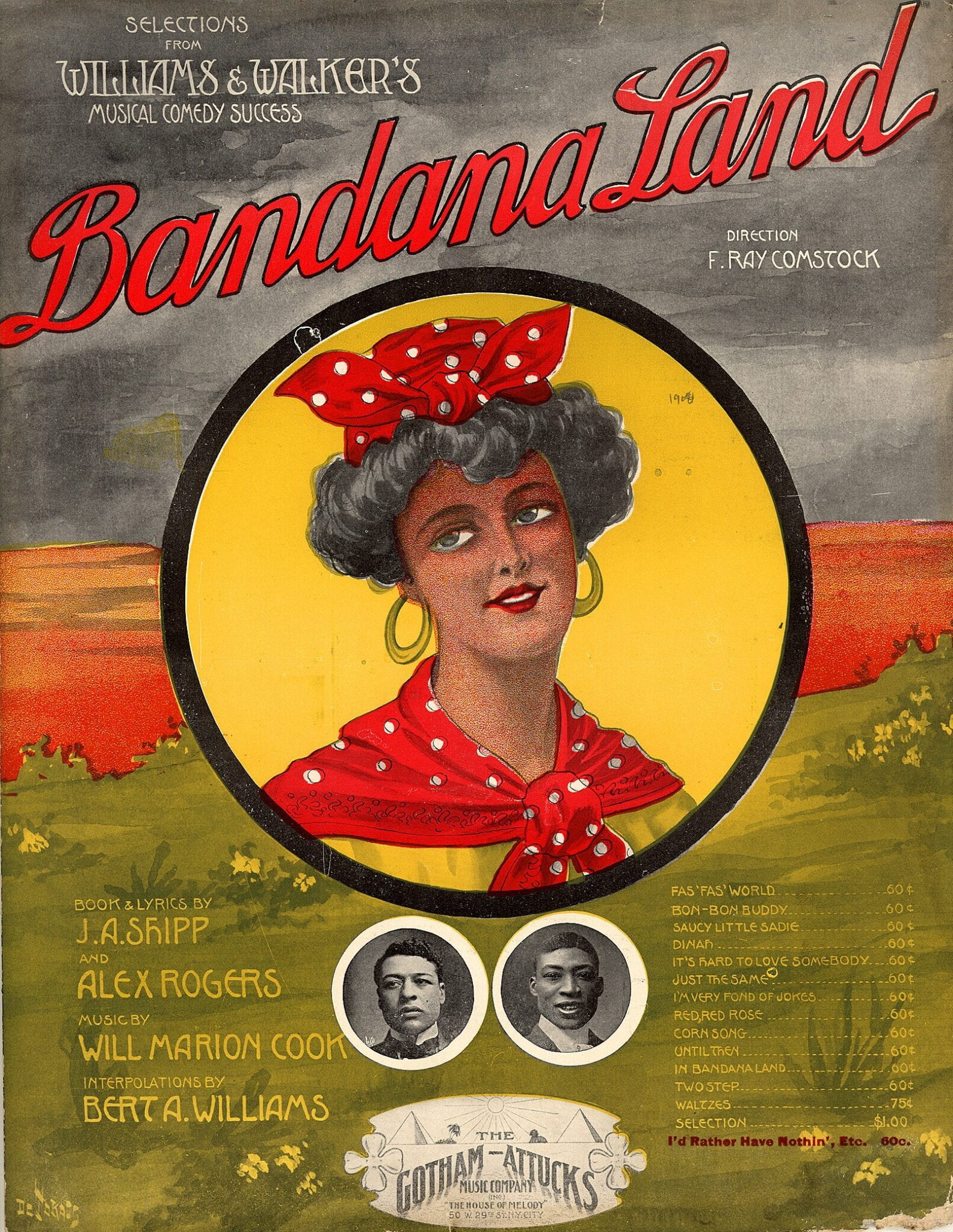

Among their many accomplishments, Williams and Walker went on to produce and star in Sons of Ham (1900), In Dahomey (1903), and Bandanaland (1908). As they established the Williams and Walker Company, the two created employment opportunities for Black performers, paying their talent generous wages and furthering Black ownership and opportunities.

In the early twentieth century, reactions to Williams and Walker’s work within the Black community varied. The duo thought of themselves as “race men,” believing their talents, popularity, and resources should be utilized for the betterment of the Black race. Certain Black publications regarded Williams’s use of blackface as inappropriate. In contrast, political leaders Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois praised their work, believing that Williams and Walker’s achievements brought humanity to the minstrel figure and further improved the conditions of Black people.

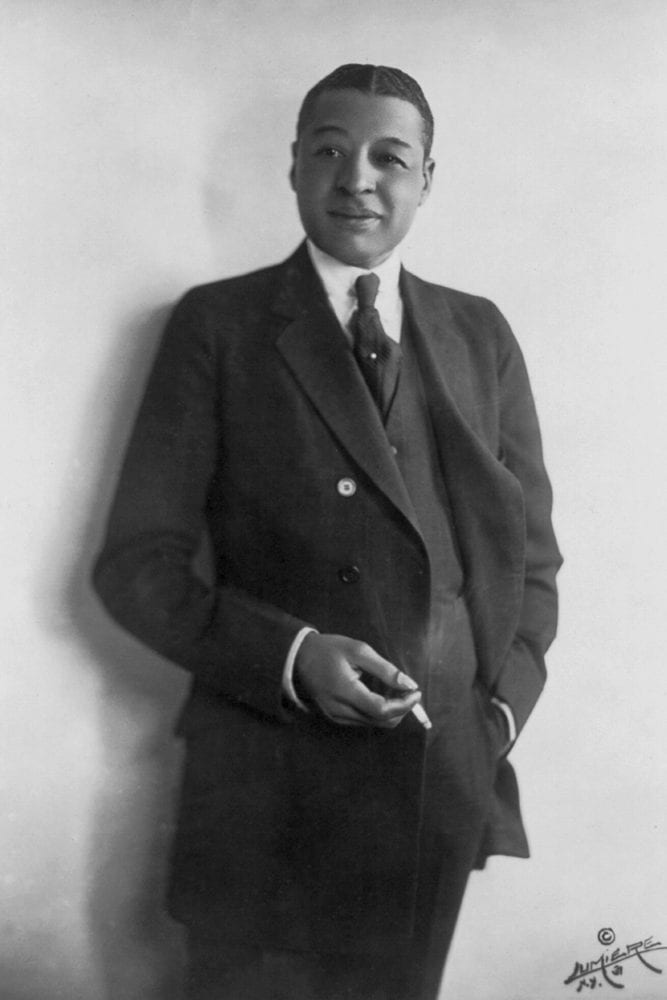

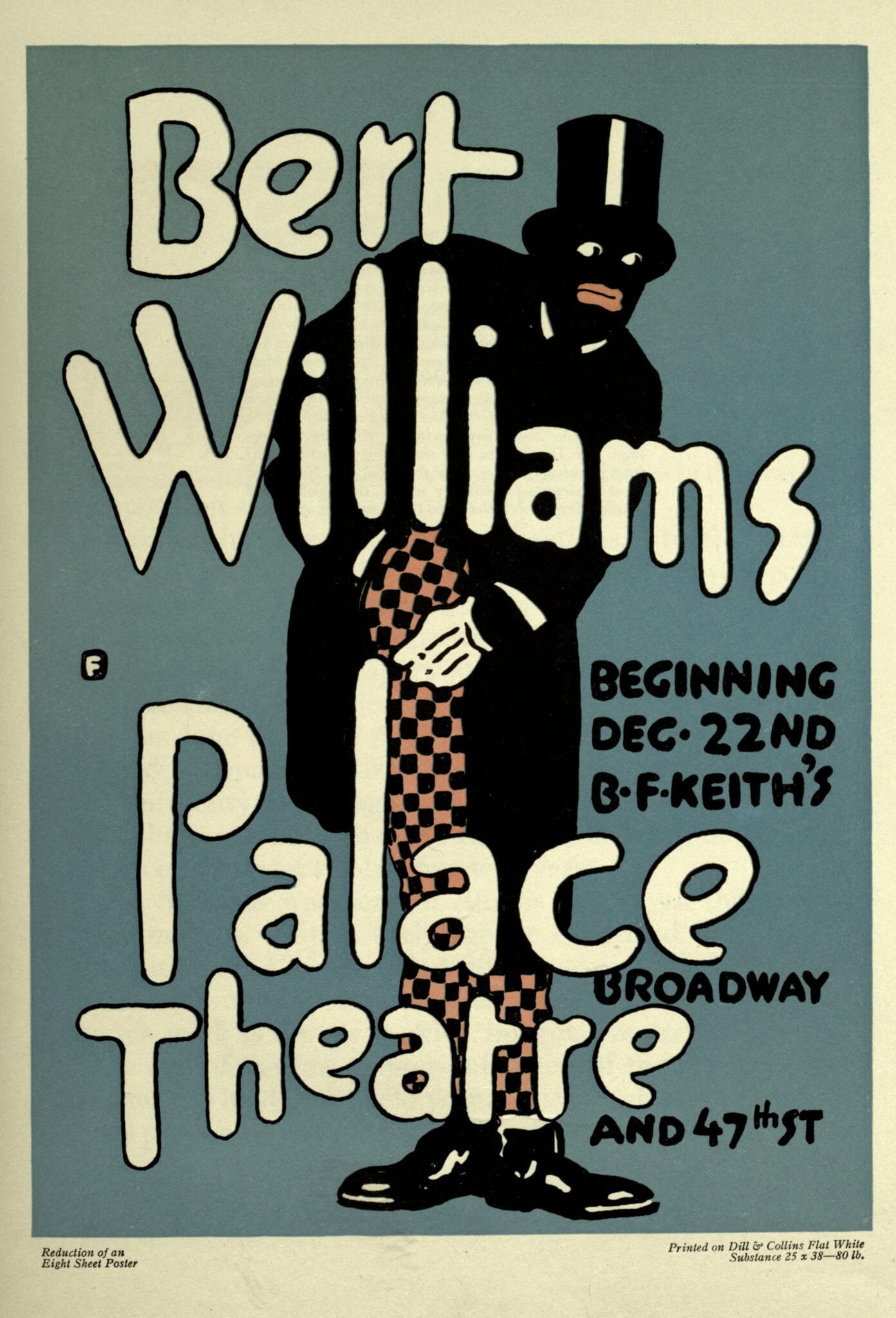

Bert Williams

“In truth, I have never been able to discover that there was anything disgraceful in being a colored man. But I have often found it inconvenient—in America.” –Bert Williams

At the height of his career, Bert Williams was a dominant figure in the entertainment industry, and central to the creation of spaces that included African American performers, creators and theater workers of all stripes. From In Dahomey to the Ziegfeld Follies, his work was revolutionary and transformative to what theater could be. Beginning with George Walker as a minstrel performer, Willliams’ pioneer work pushed the limits of what it could mean to embody an African American on the American stage: from disparaging and cruel stereotypes to fully human, complex and comedic characters. Throughout his career, Bert Williams performed in blackface, though not exclusively. He wrote, directed and starred in the 1916 silent film Natural Born Gambler, in which he is the only character in blackface. Media studies scholar Racquel Gates writes that this act, being the sole blackface performer in an almost all Black cast, “demonstrates how Black performers sometimes used the makeup as a mask to differentiate between cinematic tropes of blackness and ‘real’ Black people, a practice that indicates a keen awareness — yes, even then — of how cinema functions in relation to representation.”

In 1910, Black political leader and educator Booker T. Washington wrote that Williams “has done more for our race than I have. He has smiled his way into people’s hearts; I have been obliged to fight my way.”

Aida Overton Walker (1880 – 1914)

“I venture to think and dare to state that our profession does more toward the alleviation of color prejudice than any other profession…” –Aida Overton Walker

Aida Overton Walker, known as the “Queen of the Cakewalk,” was a singer, dancer, actor, and choreographer. In 1895, she joined the Black touring company John Isham’s Octoroons. She then joined the Black Patti Troubadours, where she became a celebrated choir member and performed alongside her future husband, George Walker. In 1898, she joined the comedy duo of Williams and Walker, whose shows she would eventually star in. She was perhaps most well known for her performances of the “Salome” dance at Hammerstein’s Victoria Theatre as well as “Miss Hannah from Savannah” in the show Sons of Ham. Overton Walker became an essential part of the success of Wiliams and Walker’s shows, working behind the scenes to supply choreography, themes, and ideas. After George Walker’s death, which occurred while the couple was on tour, she donned a suit and assumed her late husband’s roles. After a successful life on the stage, Overton Walker passed away of kidney failure at age 34.

In Dahomey

Music by Will Marion Cook. Book by Jesse A. Shipp. Lyrics by Paul Laurence Dunbar. February 18–April 4, 1903 at the New York Theater

In Dahomey was first performed on Broadway in February 1903, starring Williams and Walker and featuring Aida Overton Walker and Hattie Williams, among others. After its 53 performance run, it had a four-year US tour and a brief revival on Broadway. In London, the show was performed by “royal request” at Buckingham Palace. Although many of the songs are offensive so-called “coon” songs typical of the minstrel era, In Dahomey is significant as it was the first musical on Broadway written and performed by African Americans. It also introduced ragtime and cakewalk to Broadway musicals, and was arguably the first Broadway play to address colonialism.

Shuffle Along

Music by Eubie Blake. Lyrics by Noble Sissle. Book by Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Everyone in town is always singing this song: / “Shuffle Along. Shuffle Along.”

Doctors, bakers, undertakers, do a step / That’s full of pep and syncopation. / “Shuffle Along,” –oh, “Shuffle Along.”

Why, life’s but a chance,

and when times come to choose,

If you lose, don’t start a-singing the blues, / But you just shuffle along, / And whistle a song.

Why, sometimes a smile will right every wrong

Keep smiling and shuffle along.

The upbeat lyrics of the title song in this all-Black musical proclaimed that anyone could “Shuffle Along” and appreciate life in all its glory. From its arrival on Broadway in 1921, audiences flocked to see the performances of comedians Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles, comedians who sought to outdo each other in a political contest for mayor of their town. Shuffle Along introduced Broadway audiences to new ideas, incorporating jazz, a chorus line that could sing, dance and act with “pep,” and— most importantly—a Black love story. The show was phenomenally successful and ran for a total of 504 performances over the span of a year.

Broadway revivals followed in 1933 and 1952, and a 2016 Broadway adaptation directed by George C. Wolfe took a look at the lives of its creators behind the scenes. Theater historian Jo Tanner states that the original 1921 performance served to “legitimize the African-American musical” and launched the careers of several of the actors involved, as it proved to producers and managers that “audiences would pay to see African-American talent on Broadway.”

MORE On this Page: Minstrelsy and Blackface • Racial Terms • African Grove: Background • Legacy • Ira Aldridge • Minstrelsy • Black Skin, Blackface, Whiteface • Cakewalk • Some Minstrel Troupes • Williams and Walker • Bert Williams • Aida Overton Walker • In Dahomey • Shuffle Along

You must be logged in to post a comment.