| The artificial divine |

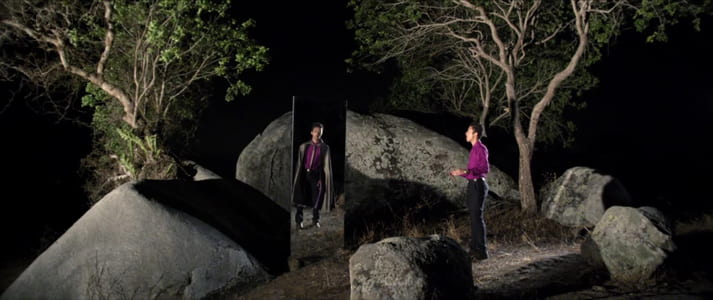

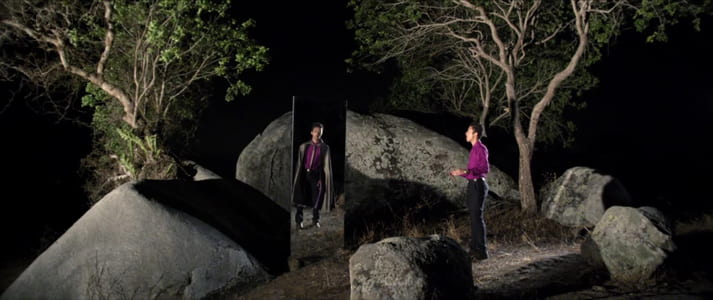

One of the most striking set compositions in Holy Tremor – a short video by the Brazilian-German duo Barbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca recently featured in the program LGBTQ Brazil, curated by Ela Bittencourt for the Museum of the Moving Image – shows a landscape of rocks interrupted by a sharp rectangular gap, as if a hole had been geometrically cut out of the location’s curves, breaking off the free flow of form provided by nature. But this doorway, this passage, is not really a gap; it is a mirror. The fracture in the landscape is produced by a visual illusion created by a strategically placed reflection – a reflection of nothing, a black hole carved out of the rocky scene. When singer Joelysson Anderson, one of the film’s performers, enters that meticulously set stage, the portal – a threshold between two different worlds – is revealed as a mirror, to then be re-revealed as a visual trick which allows the man to interact not really with his mere reflection, as Groucho Marx in Duck Soup (1933), but with a different image of himself, a double that does not match his original referent. The reflected man, only the reflected man, wears a cape given by the Father to his chosen son, pushing him from his modest upbringing into a source of jealousy for those who have not been chosen. Building of a classic analogy in cinema studies (cinema as window, mirror, or prism), the world and the man beyond the mirror are not analogous to the world before it; they are a riff, a distorted image that holds ties to what it reflects, but also reveals what it dreams to be. Success, whether divine or secular, becomes the image of desire, as much as desired image is that of success. In the scene’s manifold exchanges between two of the same which are not equal, the central tensions in Holy Tremor ripple to the surface.

This latest adventure by Wagner and De Burca is at once an inventorying documentary about contemporary neo-Pentecostalism in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil, and a decolonial pop musical. This combination alone puts the film’s theme at a productive intersection. In the article In Praise of Profanation, Giorgio Agamben defines religion through space-related metaphors that align with the filmmakers’ mirror-portal: “Religion can be defined as that which removes things, places, animals, or people from common use and transfers them to a separate sphere. (…) ‘to profane’ meant, conversely, to return them to the free use of men. (…) Not only is there no religion without separation, but every separation also contains or preserves within itself a genuinely religious core.”[i] The film’s artificial portal does more than address contemporary art’s predilection for liminal spaces and for the play between outside and inside; it stages the fundamental gesture of religion itself as that of creating separation – a doorway in a natural landscape – at the same time that it repatriates this other sphere beyond the mirror – beyond the actual world – as profane, as a sacred that is paradoxically attainable – the mismatched reflection.

The echo of Groucho Marx in the mirror scene is a revealing nod, for the mismatched reflection is only the more evident manifestation of a characteristic present throughout the film’s mise-en-scène and that is most exuberant in slapstick comedy: a sense of play. Agamben places “play” as the fundamental tool that allows for the passage from the sacred to the profane: a child can play with the most sacred or forbidden materials, profaning its intended social use, and finding a new destination for a practice or object which had been turned into a tool or a symbol. This gesture of decolonial appropriation and reinvention is prominent in another film from Pernambuco: Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Neighboring Sounds (2010), in which a vacuum cleaner is used to erase traces of pot smoke, and a washing machine becomes a temporary lover, profanating the original function of targeted consumer goods. “Modern man proves he no longer knows how to play precisely through the vertiginous proliferation of new and old games,” Agamben writes. “Indeed, at parties, in dances, and at plays, he desperately and stubbornly seeks exactly the opposite of what he could find there: the possibility of reentering the lost feast, returning to the sacred and its rites, even in the form of the inane ceremonies of the new spectacular religion or a tango lesson in a provincial dance hall.”[ii] Through musical, the man attempts to break through the mirror: if I can sing about it, I can be it.

Casting a dedicated glance on a new social identity in Brazilian society which is shaped through pop neo-Pentecostalism (neo-Poptecostalism?) and a newfound economic virility, the filmmakers suggest a profound reversion of Agamben’s degenerative view of this exchange between the sacred and the profane: what if an entire religion is built around sacralizing the profane? In the case of Brazilian neo-Pentecostalism – the Evangelicals, as they’re popularly called – the many different strands and practices found within a broad scope of religions seem to taper toward the subversion of profanation itself as a form of sacred. In a historical sense, this framework has had a number of practical manifestations in contemporary Brazil, from broadcast pastors kicking Catholic saints on national television, in 1995, to the recent proliferation of online videos of Evangelical militias forcing practitioners of afro-Brazilian religions to destroy their own places of worship.

Beyond the misrepresentation that is intrinsically tied to totalizing readings of faits-divers, this play with the profane as sacred finds a firmer ground in the open association between neo-Pentecostalism, pop music, and money. The common thread that ties together the songs in Holy Tremor is braided with narratives of personal success, material jealousy, and religious faith, locating this new face of Protestantism as the official church of Brazilian neo-liberalism. If, as Agamben himself puts it, God has become money, pop stylization has become a new form of liturgy: the profane is sacred, and the sacred is profane. The film’s last act shows a construction worker singing on a construction site. Behind him, lay the foundations of a stage. The film then cuts to a wide shot of the exterior of the location, placing that stage – that place of play – as the epicenter of a church.

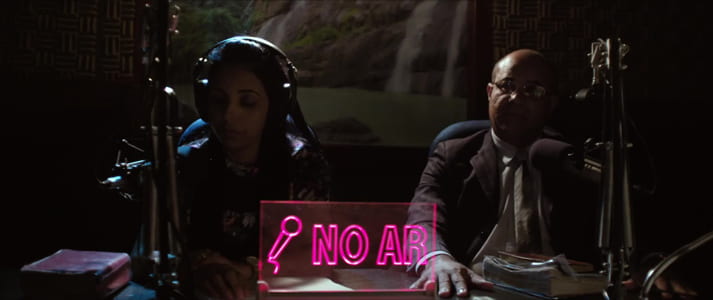

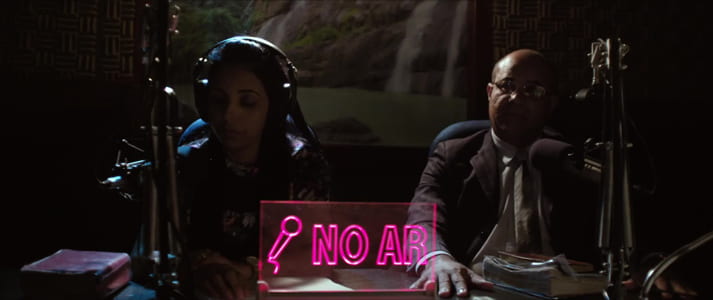

But what makes Holy Tremor truly fascinating is that the filmmaking itself engages in this profane play: if there is indeed something religious about every separation, Wagner and De Burca cleverly poke holes on durable invisible walls, at once questioning the separation between the popularity of cinema and the exclusivity of the museum (the film has circulated in both), as well as the barrier between the documentarian gaze and the social phenomenon it seeks to represent. Made in rouchian collaboration with the artists portrayed in the film, Holy Tremor is mostly comprised of musical numbers in which kitsch uncovers genuine emotion, synthesizers intertwine with the gurgling of a creek, salesman rhetoric holds hands with the gospel, natural settings collide with timed choreographies, Walter Hill’s Warriors (1979) shapes the liturgy through radio announcements and bright-colored costumes, and brechtian tableaux common to video art, performance documentation, and ethnographic film, interact with subjectivity-driven close-ups of singers groping for the divine behind impenetrably closed eyes.

It is only fair then that this battleship between proximity and distance, emotional adherence and critical repulsion, science and narrative, find its peak in the moments the film itself rejoices in the artificial divine: the intermittent use of direct address; the incorporation of the title of one of the songs as the film’s title; the cooperation between the photography to the colors in the clothes (a typical feature of Wagner’s work in both video and photography); the camera movements and cuts that are synced with the flow of the music; the offscreen fans, the shaking camera, and the bubbling water that infiltrates this unfaithful film with the double-edged sharpness of the word, but also creates a cinematic tremor that is at once holy and profane.

[i] Giorgio Agamben, Profanations (New York: Zone, 2007) 73.

[ii] Idem, 76-7.

* * *

Divino artifício

Divino artifício

Uma das mais desconcertantes construções cênicas de Terremoto Santo – vídeo de curta-metragem da dupla Bárbara Wagner e Benjamin de Burca que foi parte da exposição Corpo a Corpo, no IMS Rio – mostra uma paisagem rochosa interrompida por um recorte retangular, como se um buraco tivesse sido extraído geometricamente das curvas daquele lugar, engasgando o fluxo formal da natureza. Mas essa porta, essa passagem, não é bem um recorte; é um espelho. A fratura na paisagem é uma ilusão de ótica criada por um reflexo posicionado de maneira estratégica no cenário – um reflexo do nada, um buraco negro excavado em pedra. Quando o cantor Joelysson Anderson, um dos artistas presentes no filme, adentra palco tão eximiamente composto, o portal – passagem entre dois mundos diferentes – é exposto como espelho, e posteriormente como um truque visual que permite ao homem contracenar não apenas com seu reflexo, como Groucho Marx em Diabo a Quatro (1933), mas com uma imagem diferente de si, um duplo que se difere do original. O reflexo, e só ele, veste uma capa dada pelo Pai ao filho escolhido, impulsionando-o de uma criação modesta ao centro das atenções e da inveja dos não-escolhidos. Jogando com uma analogia clássica na teoria de cinema (o cinema como janela, reflexo, ou prisma), o mundo e o homem no espelho não são análogos ao mundo diante do espelho; são uma releitura, uma imagem distorcida que mantém laços com o corpo que ela reflete, mas revela também o que ele sonha ser. O sucesso, divino ou não, faz-se imagem do desejo, assim como a imagem desejada é um projeto de sucesso. Nas muitas trocas entre esses dois mesmos que não são iguais, as principais tensões de Terremoto Santo tremulam à superfície.

A mais recente aventura de Wagner e De Burca é, ao mesmo tempo, um inventário documental sobre o neopentecostalismo contemporâneo em Pernambuco e um musical pop decolonial. Essa combinação por si já coloca o filme em uma encruzilhada extremamente produtiva. Em Elogio da profanação, Giorgio Agamben define o conceito de religião por meio de metáforas espaciais que se alinham ao portal espelhado dos diretores: “Pode-se definir como religião aquilo que subtrai coisas, lugares, animais ou pessoas ao uso comum e as transfere para uma esfera separada. (…) ‘profanar’, por sua vez, significava restituí-las ao livre uso dos homens. (…) Não só não há religião sem separação, como toda separação contém ou conserva em si um núcleo genuinamente religioso.” [i] O portal artificial do filme vai além de simplesmente satisfazer a predileção da arte contemporânea por espaços limítrofes e pelo jogo entre dentro e fora; ele encena o gesto religioso por excelência como o de produzir uma separação – uma porta em uma paisagem natural – ao mesmo tempo que incita o repatriamento dessa outra esfera além do espelho – além do mundo concreto – como profana, como um sagrado que está paradoxalmente ao alcance das mãos – o reflexo desconexo.

A sombra de Groucho Marx na cena do espelho é reveladora, pois esse reflexo desconexo é apenas uma manifestação mais evidente de uma característica central à mise-en-scène de todo o filme que encontrou apogeu de exuberância nas comédias slapstick: a idéia de “play”, de “jogo”, de “brincadeira”. Agamben dá ao jogo papel fundamental na passagem do sagrado ao profano: uma criança pode brincar com o mais sagrado ou proibido dos materiais, profanando seu uso social desejado e encontrando nova função para aquela prática ou objeto que havia sido tornada ferramenta ou símbolo. Esse gesto de apropriação e reinvenção é muito presente, por exemplo, em outro filme de Recife: O Som ao Redor (2010), de Kleber Mendonça Filho, em que um aspirador de pó é usado para apagar os rastros da fumaça de maconha, e uma máquina de lavar vira amante temporária, profanando a função originalmente atribuída pelo capital àqueles bens de consumo. “Que o homem moderno já não sabe jogar fica provado precisamente pela multiplicação vertiginosa de novos e velhos jogos,” escreve Agamben. “No jogo, nas danças e nas festas, ele procura, de maneira desesperada e obstinada, precisamente o contrário do que ali poderia encontrar: a possibilidade de voltar à festa perdida, um retorno ao sagrado e aos seus ritos, mesmo que fosse na forma das insossas cerimônias da nova religião espetacular ou de uma aula de tango em um salão do interior.” [ii] Através do musical, o homem tenta penetrar o espelho: se posso cantá-lo, posso sê-lo.

Ao concentrar um olhar inquieto em uma nova identitidade social na sociedade brasileira forjada pelo neopentecostalismo pop (neopoptecostalismo?) e por uma recém-descoberta virilidade econômica, os cineastas sugerem uma reversão profunda da visão degenerativa que Agamben tem dessas trocas entre o sagrado e o profano: e se toda uma religião fosse erigida na sacralização do profano? No caso das religiões neopentecostais – ou evangélicas – os muitos feixes e práticas espalhados por um conjunto múltiplo de igrejas parece se afunilar rumo à subversão da própria profanação como uma manifestação do sagrado. No retrovisor da história, é esse o fio que conecta Edir Macedo chutando santos católicos na TV aberta, em 1995, e a proliferação de vídeos online de milícias evangélicas coibindo praticantes de religiões afro-brasileiras a destruírem seus próprios espaços de culto.

Mas, se ultrapassada a inevitável grosseria das leituras totalizantes a partir de eventos midiáticos, esse jogo com o profano como sagrado tem raizes mais firmes no pacto entre as igrejas neopetencostais, o pop e o dinheiro. O fio que conecta as muitas canções de Terremoto Santo é trançado com narrativas de sucesso individual, inveja material e fé transcedental, localizando essa nova face do protestantismo como a religião oficial do neoliberalismo brasileiro. Se, como diz o próprio Agamben, Deus virou dinheiro, a estilização pop virou uma nova forma de liturgia: o profano é sagrado, e o sagrado é profano. A última sequência do filme mostra um operário de construção civil cantando em um canteiro de obras. Atrás dele, esboça-se em alvenaria o contorno de um palco. O filme por fim corta para um plano geral do exterior da locação, situando o palco – o lugar do espetáculo – como o epicentro de uma igreja.

Mas o que faz de Terremoto Santo um filme verdadeiramente fascinante é que a própria realização se engaja neste jogo de profanações: se há, de fato, algo de genuinamente religioso em toda separação, Wagner e De Burca abrem buracos em velhas paredes invisíveis, questionando a separação entre a popularidade do cinema e a exclusividade do museu (o filme circula em ambos os espaços), e abalando a barreira entre o olhar documental e o fenômeno social que ele deseja representar. Realizado à maneira de Jean Rouch, em colaboração direta com os artistas retratados no filme, Terremoto Santo é uma coleção de números musicais em que o kitsch desvela a emoção genuína, sintetizadores se embaraçam nos ecos de um riacho, a retórica de vendedor dá as mãos à palavra divina, paisagens naturais se chocam com coreografias ensaiadas, Warriors – Os Selvagens da Noite (1979), de Walter Hill, enforma a liturgia via transmissões de rádio e figurinos aberrantes, e tableaux brechtianos comuns à vídeoarte, à documentação de performances, e ao documentário etnográfico, interagem com cantores que buscam o sagrado por trás de olhos fechados, em closes embebidos de subjetividade.

É questão de justiça, portanto, que esse campo de batalha entre proximidade e distância, aderência emocional e repulsa crítica, ciência e narrativa, encontre seu ápice nos momentos em que o próprio filme goza com seu divino artifício: o canto com os olhos fixos no espectador; o uso do título de uma das canções como título do próprio filme; a cooperação da fotografia com as cores das roupas (marca constante no trabalho de Wagner como diretora, mas também como fotógrafa – como fica claro em seu outro trabalho na mesma exposição, À Procura do 5o Elemento, de 2017); os movimentos de câmera e cortes sincronizados ao fluxo da música; os ventiladores fora de quadro, a câmera que balança e a água que borbulha, infilitrando este filme infiel com o fio de dois gumes da Palavra, mas criando um tremor cinematográfico que é, também ele, sagrado e profano.

[i] Giorgio Agamben, Profanações (São Paulo: Boitempo, 2007) 58.

[ii] Idem, 60.

Leave a Reply