* Originally published in Portuguese in Carla Maia and Luís Felipe Flores (ed.) O Cinema de Trinh T. Minh-ha (2015) Rio de Janeiro: Caixa Cultural. 87-91.

A room of one’s own

A Tale of Love begins with a wide shot of a mountain under blue sky, covered by dry weed that sways in the wind. At the edge of the view, a woman dressed in red appears running down the mountain, stumbling through that ancient landscape.

Cut to a face under a traditional Vietnamese straw hat (non la) and a red sky that underlines the borders of a close-up. The natural image of the mountain, although allegorical, collides with the highly artificial red, blue and yellow light that creates stripes on Kieu’s (Juliette Chen) face, in a stylized pose that echoes Wong Kar-wai’s Ashes of Time (1994). The change in proportion is no less jarring, going from a wide shot to the close-up of a face, from one extreme to another in scale. The shot widens slowly, projecting the face of the actor against a muted, infinite, impenetrable background.

Another cut, this time to a pale, sun-drenched interior: an alarm clock floats out of focus in the foreground, while the viewer’s attention inspects the topography of a body covered with a white sheet like a mountain in winter time, a small bamboo cage hanging from the ceiling, and green trees, in the background. The image is filtered by a mosquito net, creating a white fog that doesn’t bother hiding its folds. Under the sheet, covered head-to-toe, somebody is asleep. A voice off-screen shouts indistinct words, and Kieu – the woman with the hat and red fabric; the same that ran down the mountain in the beginning of it all; the very same, because later it’ll become clear that A Tale of Love is a diffracted adaptation of Tale of Kieu (1820), the epic poem by Nguyen Du that prefigures the country’s identity, mirroring it in the life of a woman who shares a surname with the protagonist of the film – suddenly wakes up and unveils the image… or is she pulling to the side the film screen itself, as if to invite the spectator to join her over there, finding comfort in a corner of that room? From the moment she woke up to the prosaic breakfast in the backyard, the reprehending voice of her aunt adds a lash of context to all those different registers: “You always look like you just woke up from a dream.”

Ah, it was just a dream… but what, precisely, was a dream? And what wasn’t one? Whose dream was it? When was it dreamt? Some flashes – foresight? Projection? A nap? – anticipate the upcoming reality: the scene of Kieu posing with the non la is re-established as a photo shoot. “I am a writer and a sex worker,” she tells her editor, much later, referencing her side job as a photographic model, which appears in the film way before she’s been established as a writer, as if to note that the body is the principle of the word. Her tongue switches between Vietnamese, during breakfast with her aunt, to English when she talks to the Western-looking photographer, who questions, hides, covers Kieu’s body, inciting a two-way form of voyeurism. But wasn’t it a dream? And is it still?

Recalling shots as a critical tool can sometimes be a boring exercise. In normal conditions, it’d be better to freeze the image during the projection and point the finger: there is the mystery I would like to talk about! But in A Tale of Love, the adaptation from image to verbal discourse is part of the absorption of the filmic experience, because it is through free (although never disorderly) association that the shots and sequences amount to a bigger, more revealing whole. The film doesn’t quite happen within the shots, but in the mental motion that takes place between them: every “what do I see?” is quickly succeeded by a “what does it tell me about what I have seen up until now?”, and a “how is it determinant to what I am seeing next?”

Of these three different movements of the gaze, the first is the simplest one: if Trinh T. Minh-ha’s cinema isn’t exactly transparent, its translucency (so many veils; so many drapes) is clear – hence the possibility of retelling its structure shot by shot (something way harder and less useful when writing about a Wong Kar-wai film, for example). The challenge of experience starts with the verb “to see”: even though clearly defined, the narrative and sensory spheres only find full meaning in the intervals left in their sequencing. One is clear about what they just saw and what they had just seen, yet the mystery remains in the blink of the eyes that jams the tracking shot between one point and the other – between an art studio filled with plastic animals and the proverbial banging of one’s head against the table in a garden that opens up with the homely expanse of a porch-circled house.

“Interval” is a word so dear to Trinh T. Minh-ha that one of her books on cinema has been baptized Cinema Intervals. Published in 1999, it collects interviews with the artist (“director” seems awfully insufficient to describe someone who’s also a poet, composer, ethnographer, scholar, professor, theorist, and writer) as well as the meticulously unconventional script of A Tale of Love. The obsession dictates the form: the interview-format is when the intervals come alive, opening up to different relationships with different viewers, which become clear in this dialectics that chooses negotiation over exclusion. However, as a guide to the interviews, she writes a plea for a pact: “(…) To keep the relation of language to vision open, one would have to take the difference between them as the very line of departure for speech and writing, rather than as an unfortunate obstacle to overcome. The interval, creatively maintained, allows words to set in motion dormant energies and to offer, with the impasse, a passage from one space (visual, musical, verbal, mental, physical) to another.”[1]

To experience A Tale of Love – her first scripted film (she prefers the word “scripted” to fiction), co-directed with frequent collaborator, Jean-Paul Bourdier – is to find joy in inhabiting the intervals, these dashes that connect, at the same time that divide: body-landscape; dream-reality; past-present; individual-collective; inside-outside. This stretching of the sensible, which Jacques Rancière sees as the true possibility of political art [2], reaches out for other spaces, which are announced in the first conversation between Kieu and her aunt: “to make a living writing, one must have a room of their own,” she says when she feels her privacy is at risk, alluding to Virginia Woolf’s landmark feminist essay. The “inside” is this room, one’s own, this intimate safe haven of the self that the nearby narration in her landmark work, Reassemblage (1982) quotes (since saying a voice is either over or off-screen feels violently inadequate): “what I see is life looking at me. (…) I’m looking through a circle in a circle of looks.” How does Kieu, the protagonist in A Tale of Love, see this other Kieu, the founding image of the country she was born and no longer lives in? How does Vietnam see her? And how do we, as integral parts of this circle of looks, retell this accidental tale?

A Tale of Love is meticulously composed to allow this circle of looks. Nothing is random, and, at the same time, every end must remain loose, as if the film had been made to reaffirm that, in cinema, one must be extremely rigorous to avoid being rigid. The editing inverts the one who looks and the one being looked at, switches the polarities of the relationships, lets itself be moved both by the trot of the narrative and the movement of the colors, the sounds, the shapes and the bodies in space.

In an interview made by Gwendolyn Foster, Trinh T. Minh-ha talks about a specific scene with Kieu and the photographer that, although shot in sequence, ended up spread apart in different extremities of the final cut. This literal separation is precisely what allows the spectator to experience the interval:

“So many things have happened in the film during this lapse of time that a multitude of questions may be raised as to both the nature of that night scene (is it a nightmare? a fantasy? a memory?) and the nature of the events that came before it (Was she telling herself stories all this time? Or was the daydream dreaming her?). No single linear explanation can account for these narrative interfaces in which performer and performance, dreamer and dream are constituted like the two sides of a coin. One cannot say that she’s simply moving in and out of fantasy and reality, but rather, that it’s a different zone we are experiencing.” [3]

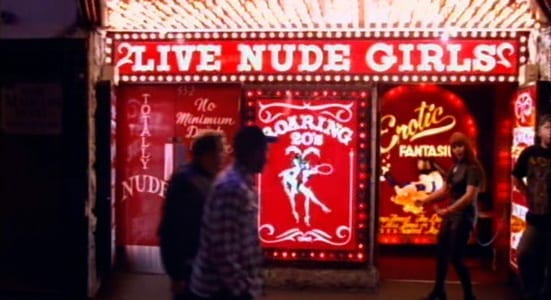

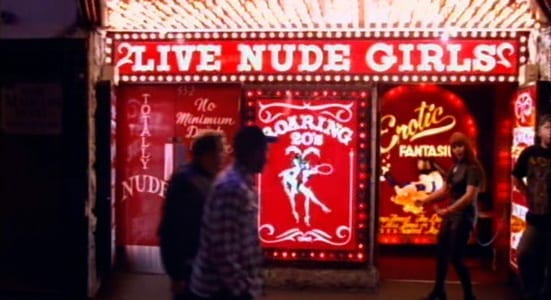

A Tale of Love proposes highly elaborate formal distensions to stage major philosophical investigations, in order to, if successful, reconcile the word and the body. Indeed, if the writer is one who loves for a living, the filmmaker is the one who allows body and spirit to reconcile, under the debris of a world of images scarred by the vulgarity of pornography and advertisement, transformed into puffy, disembodied dresses, like the dizzying subjective shots that lose sight of the subject halfway through and float down foreign cities like wandering ghosts, waiting for the first woman by the door of a strip club to invite you in.

If the extreme self-awareness positions the film at the heart of modern cinema – taking paths as distinct as those who’ve led to Reassemblage and Night Passage (2004), the films by Trinh T. Minh-ha seem primarily concerned with redefining apprehensions of time and space within cinema, in infinite layers of self-reflexivity – the procedures described here pave the nature of the room (of one’s own). “Do not mistake natural with nature”, her editor advises, in one of the many dialogues in the film that are capable of opening door after door in our perception of the world and of cinema itself. A Tale of Love puts tension in these relations, pushing words until they’re on the verge of song, movements on the verge of dance, passions on the verge of history, and nature on the verge of artificiality. As this strand of intervals, the film by Trinh T. Minh-ha and Jean-Paul Bourdier stands as one of the most destabilizing and fascinating missing links of contemporary cinema.

* * *

[1] Trinh T. Minh-Ha, Cinema Intervals. Routledge, New York, 1999. P. xi.

[2] “(…) art isn’t political for the messages it transmits, nor for the way it represents social structures, political conflicts or social, ethnical and sexual identities. It is political first and foremost because of the way it configures a space-time sensorium that determines ways of being together or apart, inside or outside, in the face of or in the middle of… It is political when it cuts out a specific space or a specific time, when the objects with which it fills this space or the pace it lends this time determine a specific form of experience, either in conformity or in rupture with others: a specific form of visibility, a modification of the relations between sensible forms and regimes of meaning, specific speeds, but also and above all things forms of gathering and of loneliness.” Jacques Rancière, A Política da Arte, my translation from Portuguese.

[3] In Darrell Y. Hamamoto & Sandra Lyu. Countervisions: Asian American Film Criticism. Temple University Press, 2000. 208.

* Publicado originalmente em Carla Maia and Luís Felipe Flores (ed.) O Cinema de Trinh T. Minh-ha (2015) Rio de Janeiro: Caixa Cultural. 87-91.

Um quarto só seu

Um Conto de Amor abre com um plano geral de uma montanha sob o céu azul, coberta por um capim seco que balança ao vento. No limite da visão, surge uma mulher vestida de vermelho que, aos tropeços de uma corrida, desce por toda aquela paisagem ancestral.

Corte para um rosto, ornado por um tradicional chapéu de palha vietnamita (non la) e um véu vermelho que reafirma as bordas de um close up. A imagem natural da montanha, mesmo que um tanto alegórica, se choca com a artificialíssima luz vermelha, azulada e amarela que recorta, em tiras, o rosto de Kieu (Juliette Chen), em uma estilização posada que remete a Cinzas do Passado (1994), de Wong Kar-wai. Da mesma maneira, a câmera passa de um grande plano geral para o minucioso close up de um rosto, indo de um extremo a outro da escala. O plano se abre lentamente, projetando o rosto da atriz contra um fundo neutro, infinito, intransponível.

Novo corte, desta vez para um interior diurno de tons dormentes: um despertador se perde em primeiro plano desfocado, enquanto a atenção se esvai para a topografia de um corpo deitado sob um pano branco como uma montanha a receber o inverno, uma pequena gaiola de bambu pendurada no teto e árvores verdes, ao fundo. A imagem, porém, chega filtrada por um véu de mosquiteiro, bruma branca que não se preocupa em esconder suas dobras. Sob o lençol, coberta até a cabeça, dorme alguém. Uma voz fora de quadro grita palavras indistintas, e Kieu – a mesma do chapéu com o tecido vermelho; a mesma que corria pela montanha do princípio de tudo; a mesma, pois mais à frente se descobre que Um Conto de Amor é uma adaptação difratada de Conto de Kieu (1820), poema épico de Nguyen Du que prefigura a identidade do país, espelhando-a na vida de uma mulher que compartilha o nome com a protagonista do filme – acorda de súbito e descortina o véu… ou estaria ela puxando a tela do cinema, como a convidar o espectador a tomar parte do lado de lá, instalando-se em algum canto daquele quarto? Do despertar na cama ao momento prosaico de um café ao quintal, uma fala da tia, em tom de repreensão, ensaia trazer a todos aqueles múltiplos registros um cílio de contexto: “Você parece sempre ter acabado de acordar de um sonho”.

Ah, era um sonho… Mas o que, exatamente, era sonho? E o que não era? Sonho de quem? Sonho de quando? Alguns flashes – antevisão? Projeção? Cochilo? – antecipam a realidade seguinte: a cena de Kieu posando com o non la se faz realidade em uma sessão de fotos. “Sou uma escritora e uma trabalhadora do sexo”, diz ela, mais tarde, à sua editora, fazendo referência a seu trabalho paralelo como modelo fotográfico, que toma carne no filme antes mesmo de sua escrita, como se a afirmar que o corpo é o princípio do verbo. A língua salta do vietnamita, do café da manhã com a tia, para o inglês do fotógrafo de traços ocidentais, que pede, esconde, cobre o corpo de Kieu, incitando um voyeurismo de mão dupla. Mas não era um sonho? Ou será que ainda é?

A rememoração de planos como artifício crítico pode ser exercício entediante. Normalmente, melhor seria congelar a imagem e apontar com o indicador ao plano frisado: cá está o mistério de que quero falar. Mas, em A Tale of Love, a transposição da imagem para o discurso verbal é parte da absorção de sua própria experiência, pois é no enfileiramento livre, mas nunca desordenado, dos planos e sequências que o filme se constrói e se revela. Enfileiramento, porque o filme não se dá no plano, mas no movimento mental entre os planos: todo “o quê vejo?” é rapidamente sucedido por “o que isso me diz sobre o que vi anteriormente?”, e “como isso é determinante para o que verei a seguir?”.

Desses três movimentos do olhar, o primeiro é o mais simples: se o cinema de Trinh T. Minh-ha não é exatamente transparente, sua translucidez (tantos véus; tantas cortinas) é límpida – daí a possibilidade de recontar plano a plano (algo mais difícil e menos fértil de se fazer com os filmes do já citado Wong Kar-wai, por exemplo). O desafio da experiência, porém, começa após o “ver”: embora muito claramente definidas, essas esferas narrativas ou sensórias encontram pleno sentido justamente nos intervalos deixados em seu entrecruzamento. Sei o que vi agora e o que havia antes acabado de ver, mas o mistério permanece no piscar de olhos que trava o traveling entre um ponto e outro – de um ateliê cheio de bichos falsos a bater cabeça sobre a mesa até um jardim que se abre com a expansividade caseira de uma varanda.

“Intervalo” é palavra tão cara a Trinh T. Minh-ha que um de seus livros sobre cinema foi batizado Cinema Intervals. Lançado em 1999, ele reúne entrevistas com a artista (“diretora” é termo insuficiente para descrever alguém que é também poeta, compositora, etnógrafa, acadêmica, professora, teórica e escritora), além de trazer a íntegra do roteiro – tão meticuloso quanto pouco convencional – de A Tale of Love. A começar pelo próprio formato: é nas entrevistas que os intervalos entre as diferentes relações com o filme mais claramente se materializam em uma dialética que nada exclui, e tudo negocia. Como guia às entrevistas, porém, ela escreve uma solicitação por um pacto: “Para manter aberta a relação da linguagem com a visão, é necessário tomar a diferença entre ambas como a linha de partida para o discurso e a escrita, e não percebê-la como um inconveniente obstáculo a ser superado. O intervalo, se mantido criativamente, permite que as palavras despertem energias dormentes e ofereçam, com o impasse, a passagem de um espaço (visual, musical, verbal, mental, físico) a outro”. [1]

Experimentar Um Conto de Amor – o primeiro longa-metragem roteirizado (ela prefere o termo à ficção) dirigido por Trinh T. Minh-ha, co-assinado por seu frequente colaborador Jean-Paul Bourdier – é se permitir habitar esses intervalos, esses traços que conectam, ao mesmo tempo que distinguem: corpo-paisagem; sonho-realidade; passado-presente; individual-coletivo; dentro-fora. Esse tensionamento do sensível, que Jacques Rancière vê como a verdadeira possibilidade de uma arte política[2], aqui ganha outros espaços, anunciados logo na primeira conversa entre Kieu e sua tia: “para ganhar a vida escrevendo, é preciso ter um quarto só seu”, ela diz, referindo ao clássico ensaio feminista de Virginia Woolf, Um Quarto Só para Si, no momento em que sente a privacidade de seu quarto em risco. O “dentro” é esse quarto, esse seu, esse recanto íntimo do sujeito que cita a narração paralela (pois over ou off parecem termos inadequados) de Reassemblage (1982): “o que vejo é a vida olhando pra mim. (…) Estou olhando em um círculo, em um círculo de olhares”. Como Kieu, a protagonista de A Tale of Love, olha para essa outra Kieu, imagem fundadora do país onde ela nasceu e não mais vive? Como o Vietnã olha para ela? E como nós, partes integrantes desse círculo de olhares, recontamos esse acidentado conto?

Um Conto de Amor é meticulosamente composto para permitir esse círculo de olhares. Nada é aleatório, ao mesmo tempo em que nenhuma ponta se fecha, como se o longa estivesse permanentemente a afirmar: no cinema, é preciso ser rigoroso para que os filmes não sejam rígidos. A montagem, aqui, inverte quem olha e o que é olhado, troca as polaridades das relações, se deixa levar tanto pela passada narrativa quanto pelos movimentos das cores, dos sons, das formas e dos corpos no espaço.

Em entrevista a Gwendolyn Foster, Trinh T. Minh-ha fala de uma cena específica entre Kieu e o fotógrafo que, embora filmadas em sequência, terminaram em extremos distantes na montagem final. Essa separação literal é justamente o que permite, ao espectador, o intervalo de apreensão:

“Tantas coisas já aconteceram no filme neste ínterim que uma infinidade de questões pode ser levantada em relação à natureza da cena noturna (é um pesadelo? Uma fantasia? Uma lembrança?) e à natureza dos eventos que a antecederam (ela estava o tempo todo contando histórias a si mesma? Ou seu sonho-acordado a sonhava?). Não há uma explicação linear única que possa dar conta dessas interfaces narrativas nas quais o ator e a performance, o sonhador e o sonho, são como duas faces de uma mesma moeda. Não é possível dizer que ela está simplesmente entrando e saindo na fantasia, retornando à realidade; em vez disso, pode-se dizer que nós estamos experimentando uma outra dimensão”. [3]

O que é possível dizer é que Um Conto de Amor propõe elaboradíssimas distensões formais para investigar grandes inquietações filosóficas e, com isso, quem sabe, poder reconciliar palavra e corpo. Afinal, se o escritor é aquele que ama como profissão, o cineasta é aquele que promove o reencontro entre a aparência e o espírito, sob os escombros de um mundo de imagens carcomidas pela vulgaridade da pornografia e da publicidade, transformadas em vestidos armados, mas sem corpo, como os vertiginosos travelings subjetivos que perdem o sujeito no meio do caminho, e vagam pelas grandes cidades estrangeiras feito almas penadas, à espera do convite da primeira mulher à porta de um strip club.

Se a autoconsciência das operações coloca o filme no seio do cinema moderno – em caminhos tão distantes quanto os de Reassemblage e Night Passage (2004), os filmes de Trinh T. Minh-ha parecem sobretudo preocupados em redefinir apreensões do tempo e do espaço no cinema, em camadas infinitas de auto-reflexividade – os procedimentos são o ladrilho que leva à natureza do quarto, aquele que é só seu. “Não confunda o natural com a natureza”, aconselha a editora, em um dos vários diálogos do filme capazes de abrir portas e mais portas na percepção do mundo e do próprio cinema. Um Conto de Amor tensiona essas relações, construindo-se em palavras que estão sempre prestes ao canto, em movimentos sempre prestes à dança, em paixões sempre prestes à história, em naturezas sempre prestes ao artifício. Nesse feixe de intervalos, o filme de Trinh T. Minh-ha e Jean-Paul Bourdier permanece como um dos mais fascinantes e desestabilizadores elos perdidos do cinema contemporâneo.

———————————-

[1] Trinh T. Minh-Ha, Cinema Intervals. Routledge, New York, 1999. P. xi.

[2] “(…) a arte não é política antes de tudo pelas mensagens que ela transmite nem pela maneira como representa as estruturas sociais, os conflitos políticos ou as identidades sociais, étnicas ou sexuais. Ela é política antes de mais nada pela maneira como configura um sensorium espaço-temporal que determina maneiras do estar junto ou separado, fora ou dentro, face a ou no meio de… Ela é política enquanto recorta um determinado espaço ou um determinado tempo, enquanto os objetos com os quais ela povoa este espaço ou o ritmo que ela confere a esse tempo determinam uma forma de experiência específica, em conformidade ou em ruptura com outras: uma forma específica de visibilidade, uma modificação das relações entre formas sensíveis e regimes de significação, velocidades específicas, mas também e antes de mais nada formas de reunião ou de solidão.” Jacques Rancière, A Política da Arte.

[3] In Darrell Y. Hamamoto & Sandra Lyu. Countervisions: Asian American Film Criticism. Temple University Press, 2000. 208.

Leave a Reply