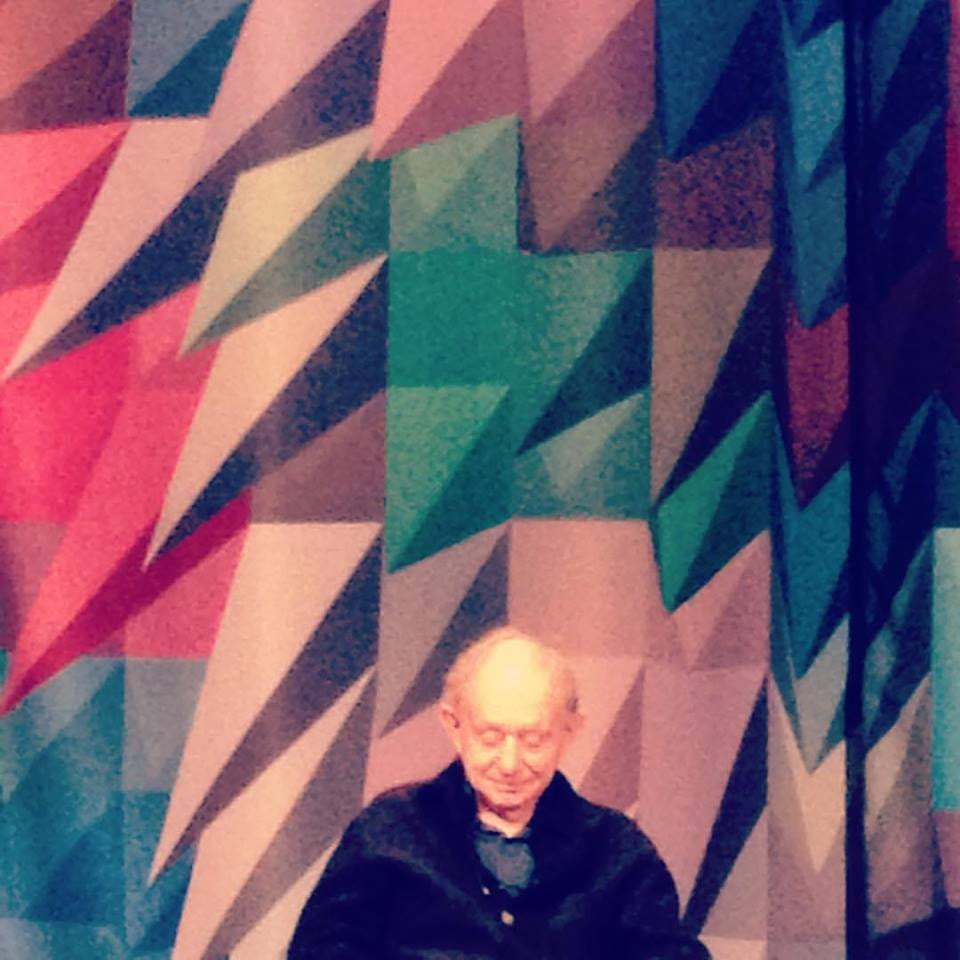

Notes from last year’s masterclass with Frederick Wiseman, at the Museum of the Moving Image (his words, filtered and probably reimagined by me), that came back to mind after yesterday’s (first and much belated) viewing of Titicut Follies (1967) on a stunning new 35mm print playing at Metrograph:

“The institution thing is a bit of a gimmick. What an institution brings is boundaries. So everything that happens within those boundaries is of interest to the film.”

“If I’m shooting and someone asks me how the camera works, I show them. I show them how the sound recorder works. It doesn’t happen often, but I do whatever I can to demystify the process. I try to present myself and the crew in a very unobtrusive way.”

“My great secret in getting permission, and I’m going to share it for the first time in my career now, is that I ask. (…) I really don’t understand why anybody allows themselves to be photographed, but as a matter of fact we do.”

“We all think our behavior is okay. And of course we don’t see our behavior the way other people see it. That’s why movies like mine can be made.”

“There is only one rule in this kind of filmmaking: once you start shooting, you keep shooting. You can’t start and stop, because everybody knows that the minute you stop something great is going to happen.”

“I can’t overestimate the importance of chance, but it is chance that has to be followed by judgement. Especially in the editing.”

“A sequence has to work on both a literal and an abstract level. The literal is what happens, what people are wearing, what they are saying, etc. The abstract is what is being suggested by the sequence and between the sequences.”

“Errol Morris once wrote an article that said I was the undisputed king of misanthropic filmmaking, and that’s a clear example of self-projection.”

“The stories in my films are really interesting and often very funny, in a sad comedy kind of way. But I’m interested in the complexity. I’m not the first person to realize that life is ambiguous. By watching a film like Welfare, I hope you get to learn something about the welfare system. Not only about the diversity and variety of people, but also about where your tax money goes, how it is distributed, how it works.”

“I’ve made four dance films, if you consider Boxing Gym a dance film, which I do.”

“I got a call one day that said ‘Mr. Kubrick wants to rent Basic Training. Important people act like that, ’cause they think they can have the films. It took a year for me to get the 16mm print back, and when I watched Full Metal Jacket I understood why: the first half of the movie is almost a shot-by-shot recreation of Basic Training.”

“What happens in our lives is also funny. What I try not to do is to edit a sequence in a way to bring the comedy out of it. I’d make a fool of myself if I was twisting the material around just to make it funny. But if the situation itself is funny, I don’t see why I shouldn’t keep it in a movie.”

“I miss shooting on 16mm, and most of all I miss editing on 16mm. That’s probably just because I was editing on a Steenbeck for 40 years, but at the risk of sounding pretentious, there’s something artisanal about physically touching the film. Avid is faster, but that’s not necessarily a good thing. 50% of the editing is thinking about what you’re going to do, so when you had to go back and check the reels you were not wasting time, but thinking about what to do next.”

“I think the structure I come up with in the editing is novelistic. I try to work on a dramatic narrative structure for my movies. The editing is a combination of a rational process with an irrational process, but no matter how irrationally I arrive at a cut, I still have to rationally justify it to myself.”

“I normally take two weeks of vacation after I shoot a movie. Then I look at all my rushes, which takes about 6-7 weeks. At this stage, I normally separate 40-50% of the material that I think will be in the movie, and put the rest to the side. From that, I start editing the sequences, without any idea on how they’ll go together in the structure. This process takes about 7-8 months, and by the time I’m done I already have an idea of the structure. I spend about two weeks assembling the structure, but that of course after 7 or 8 months of editing already. By this time, the cut is normally about 30-40 minutes longer than the finished movie will be. I work within the sequences and play with their order, until I feel like I have the movie. At that stage, I go back to the rushes I’d put to the side and check everything again. Sometimes an image I didn’t think would be useful ends up finding a place in the movie at this stage. And then, a couple weeks after I’m done, I start feeling anxious and it’s time to start thinking about the next film. It’s a fun process. It’s very physically and intellectually demanding, but it’s fun. It passes the time.”

“With every movie I have to sing for myself and get the money to make it. The moment I take for granted that I should get the money just because I’ve made a lot of movies will be the moment I should stop.”

“Human behavior is fascinating and strange.”

More on the movie soon.

Leave a Reply