One of the first works a visitor encounters when entering MoMA PS1’s Greater New York exhibition is a huge projection of a digital transfer of James Nares’ 1976 Super 8 film, Pendulum. Set in the ground level shaft, the big screen stands against the museum’s exposed brick walls, creating a kind of trompe l’oeil effect with the Chelsea walls seen in black and white in the film, while also serving as a metalinguistic landmark for the exhibition, suggesting its start with a work that dates back to the year of foundation of MoMA’s contemporary art exhibition space. The connection between place and work is, therefore, immediately established.

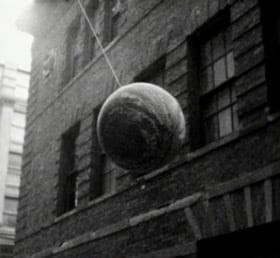

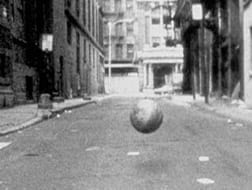

As such, the context of the fourth iteration of the exhibition – as stated in the opening text, a show dedicated to the work of emerging and more established artists who live and work in New York City, a city “being reshaped by a voracious real estate market that poses particular challenges to local artists” – promptly lends meaning to the film’s opening scene: a jerky handheld shot approaches an alley, from where a metal ball hanging from a cable swings in and out (of frame). One doesn’t even need the hollow blasts very much present on the soundtrack to understand the analogy: is it a pendulum, like the title suggests, or a wrecking ball? If every wrecking ball is, in fact a pendulum, is every pendulum also a wrecking ball?

Nares’ approach to this opening shot actualizes an impression Thomas Elsaesser often states in his writings about the moving image in the museum: the intersection between cinema and the museum allows a gallery work to reveal something about cinema, at the same time that the contradictory presence of cinema in the museum reveals something about the museum. About a year ago, I came across a work that materialized that paradox with clear intensity, when Chinatown’s Miguel Abreu Gallery showed a masterful three-screen video installation by James Benning called Tulare Road (2010).

The setting had a very specific effect: when looking at the three often deserted stretches of road projected on the screens, every now and then the sound of a car would pop on the soundtrack, even though there was no sight of cars on any of the roads. Suddenly, a red truck would appear in the distance in, say, the middle screen, provisionally matching the movement that the sound anticipated. But the marriage that the viewer assumed between sound and image was then quickly disrupted by a car coming from behind the camera on the first screen, taking the sound away with it, again forcing the viewer to reorganize his relationship with what they’re seeing and hearing (and, as a matter of fact, sometimes the sound of cars was actually coming not from the surround speakers, but from the traffic outside the gallery, invading/interacting with the exhibition space in a way that it normally wouldn’t in a film theater). In a global context where cinema seems to be going through an intense process of de-dramatization – even in Hollywood blockbusters, with the rehabilitation of a cinema of attractions – those brief moments that the three-screen video installation produced between wondering where the sound is coming from, thinking that you’ve found the corresponding source and finally being surprised by its origin, generated and taught cinematic drama: “anticipation mingled with uncertainty”, in the canonic words of William Archer.

In Nares’ super 8 film, it’s also a matter of drama, of questions stretched wide open: a pendulum or a wrecking ball? For about a minute, the revelation is withheld, until that image of apparent destruction is revealed as a tool of pure motion, swinging freely on an open alleyway. May this carefree movement not relieve the ball of its proper weight: the destruction hasn’t started yet. As a piece built on “anticipation mingled with uncertainty”, Pendulum is driven by a permanent impression of imminent danger. What looks harmless at first gets progressively more threatening, not only to the walls and the street, but also to the camera, at one point literally crushing the shadow of James Nares, who shoots in bird’s eye view from the same platform where the ball is hanging from.

All these elements could easily allow the film to be hijacked and used as an anachronistic piece of anti-gentrification propaganda – which, in a way, the museum’s textual presentation does. However, one central shot in the film states things as for more complicated than that: Nares attaches the camera to the ball, not only giving it a point of view, but also establishing a kind of complicity between the two. Pendulum, the museum card says, was the first film the artist shot when he moved from London to New York, at a point when the SoHo studios art scene was already a blooming reality, and the influx of galleries in Chelsea, the very neighborhood where the movie is shot, wouldn’t start happening for at least another ten years. As a premonitory piece (and every piece so clearly emptied out of interpretational meaning absorbs anachronistic appropriations as part of its very essence), the film’s main interest lies in revealing the ties that bind the many different stages and agents of a city’s transformation process, staging the contradiction that allows its existence and the responsibility it plays on the issue it problematizes: the pendulum, the wrecking ball, the camera and the artist sometimes get to be one and the same.

* Seen on digital projection at MoMA PS1 Greater New York exhibition, which closes March 7th, 2016.

Leave a Reply