Dr. Seema Yasmin

Clinical Assistant Professor at Stanford University’s Department of Medicine

A medical doctor turned journalist takes on misinformation

Dr. Seema Yasmin has learned to bridge her two passions: journalism and medical sciences.

She studied biochemistry at the University of London and received a medical degree from the University of Cambridge. She also studied journalism at the University of Toronto.

Yasmin merged these worlds during her time as a health and science reporter for the Dallas Morning News. Her previous experience as an epidemic intelligence service officer for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) made Yasmin a key contributor during the Ebola outbreak in Texas.

Her coverage caught the eye of CNN, who then hired her as a medical analyst.

In 2017, Yasmin was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in breaking news for her Dallas Morning News team’s coverage of a mass shooting. She is also an Emmy-winning journalist, author, medical doctor, scientist, and professional speaker.

Yasmin is currently a clinical assistant professor at Stanford University’s Department of Medicine, and the director of the Stanford Health Communication Initiative. She is also a visiting assistant professor of crisis communications at the Anderson School of Management at UCLA.

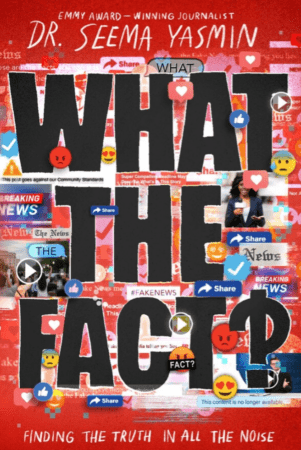

She has written pieces for the New York Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Scientific American, and Poynter. She is also the author of five books, including “What the Fact?!,” which focuses on media literacy, fact-based reporting, and the ability to discern truth from lies.

By Tiffany Corr

I want to do away with this term of “fake news.” It’s so vague, it has become a dustbin term that is used to discuss a whole mishmash of types of false information. It’s also a term that’s been weaponized, used as a word grenade that’s launched toward journalists and others who hold the powerful to account.

By being specific and saying, “We’re looking at misinformation here, or we’re looking at disinformation there,” we can have a much more effective conversation about what the problem is that we’re tackling.

I say that also with my physician hat on: You can’t treat a condition until you’ve made a proper diagnosis. You can then use evidence-based approaches to deal with it.

I cut my teeth in journalism at a local newspaper. I often frame local news as the immune system of democracy.

How Disinformation Affects Democracy

“Misinformation” is false information that’s shared without the knowledge that it’s false and without the intent to cause harm.

“Disinformation” is false information shared with the intention of seeding chaos, panic, and disorder. It’s very targeted. It’s very cleverly engineered to go viral to land with the people who are most susceptible to believe these disinformation campaigns.

For decades, people have been studying human vulnerabilities to information. They’ve been exploiting our need for certainty, especially at times of crisis, when there are more questions than there are answers about a disaster or about a political situation.

I cut my teeth in journalism at a local newspaper. I often frame local news as the immune system of democracy.

The bad actors who are targeting us do their homework — they’re making a diagnosis of all that’s wrong in our society, and saying we want to interfere with American democracy, we want to mess around with American elections. They target tensions in society along lines of race, gender, or sexuality, deepening them to stoke that polarization in a way that enables and empowers them to meddle with elections and to take apart democracy.

Researchers at the Stanford Internet Observatory are showing us where these bots and trolls originate from, whose agenda they are furthering, what tactics they are using.

We’re realizing that these voices on Twitter that we thought were American voices or British voices are accounts run out of St. Petersburg, for example, or other parts of the world, where there is a motive to meddle with America’s political system.

It’s a disinformation playbook. It’s not that new, it’s just using newer technology.

Do Algorithms Really Know What We Want?

We’re seeing studies that suggest young people aren’t going to Google even as a search engine. Instead, they are searching TikTok. When you ask them what they are looking for, the answer in focus groups is usually, “Well, I don’t know what to search for, TikTok knows me and what to show me.”

There’s this passiveness toward how young people engage with news. They certainly don’t feel empowered. This idea that the algorithms know us and the algorithms know what we need to know frightens me, to be frank.

I mentioned this in my book “What the Fact?!,” that the Guardian did analysis and the Lowy Institute did these studies that show you can be on TikTok in the morning, looking up fitness videos, and about 24 hours later be exposed to pro anorexia content on TikTok, even though the platform says it has banned that content.

Similarly, because of the connections to the Chinese Communist Party, you can be on TikTok at 9 am looking up some kind of political content, and not that many hours later be bombarded with pro-Chinese, anti-Taiwanese-independence content.

I find it really useful that journalists are doing that kind of analysis and engagement with TikTok.

In terms of journalists putting their own content on TikTok, the thing that we always say, especially in local news, is to meet the audience where they are. If they’re on TikTok, then yes, you need to be on there.

You’ll hear me say, “Subscribe to your local newspaper! Subscribe to your local news organization!”

But absent a conversation about how we consume that news, how we engage with that news, and how we consider the way that local news has maintained the status quo over the centuries, it’s not that helpful to just jump around shouting “support local news.”

We need to offer the public, especially young people, frameworks for understanding and engaging with local news. That’s everything from understanding concepts like agenda setting, gatekeeping, and framing to thinking about visual literacy and how photojournalism impacts our understanding of a story.

We have to think about what is considered consensus by journalists, to the point that we maintain the status quo without realizing we’re not always doing our job of holding the powerful to account.