The History of Washington Square Park

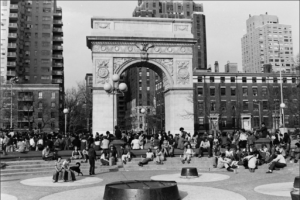

“I walked for hours from park to park. In Washington Square, one could still feel the characters of Henry James and the presence of the author himself. Entering the perimeters of the white arch, one was greeted by the sound of bongos and acoustic guitars, protest singers, political arguments, activists leafleting, older chess players challenged by young. This open atmosphere was something I had not experienced, simple freedom that did not seem to be oppressive to anyone.” (Smith, 27)

Smith describes the freedom that New York, and specifically Washington Square park has to offer. The park serves as a stage for anyone to express themselves in whatever manner they want, whether it be by bongos, in protests, through leafleting or through chess. This New York sense of freedom parallels Smith’s new sense of freedom as she goes to New York in order to become an artist. Like Washington Square, Smith feels that New York is offering her a stage to be the person that she wants to be. Furthermore, Smith acknowledges the history of the space in which she is occupying with a reference to Henry James. This idea that people still remain in spaces like an ever changing, collective collage through time is significant as now Smith herself, by just stepping into the park, will be adding to the historical weight that Washington Square park has.

In terms of the long, rich history of Washington Square Park, Smith finds herself as part of just a small blip of this history, yet this blip is one of the most iconic moments of the park. Serving originally as a farm and burial ground for the victims of yellow fever in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, the land was then used for the Washington Parade Grounds, in celebration of George Washington and the fifteenth anniversary of the signing of declaration of independence. The land was then recognizes as essential to New York as people began to take residency around the land (Folpe).

Henry James, whom Patti Smith references when talking about Washington Square Park, said in his novel Washington Square that the area around the square had a “riper, richer, more honorable look – the look of having had something of a social history.” (Folpe) James’ grandmother actually lived on the corner of Washington Square at 18 Washington Square North and James often visited her as a young boy in the 1840s. James is also quoted as saying this about the area around the Square: “I know not whether it is owing to the tenderness of early associations, but this part of New York appears to many persons the most delectable. It has the kind of established repose which is not of frequent occurrence in other quarters of the long shrill city.” (Folpe) James projects a very romanticized view of Washington Square and the Greenwich Village, a view that Patti Smith definitely latched on to as the minute she steps inside the park, she feels “the presence of the author himself” still within the park.

As history would continue however, Washington Square would go through many other events and changes such as the camping out of troops of the Gettysburg Address during the draft riots, the construction of the arch and fountain, the Square becoming a park official in 1895 and the threats of destruction by Robert Moses. However, it was in the early twentieth century that the park first began to see itself as a stage for protest and public communal gatherings. At the end of the first World War, the park became a home to a large youth population including artists, writers, activists, and radicals as they fought for women’s rights, pacifism and labor rights. The most notable public gathering of this period was after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory burned down, killing 146 people (mostly young immigrant women). A week after the fire, thousands of people gathered in the park to mourn and remember the victims. A year later, more than 20,000 people would march down fifth avenue to the Square to protest for better working conditions. Thus the park began to become a meeting place, a stage or a venue for public gathering and events to take place (Folpe).

After Robert Moses was denied from trying to turn the park into a highway, the park became completely traffic free and drew even more artists like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez along with Allen Ginsberg in the 1960s. The park would then be remodeled again around this time by poet, protester, playwright and playground builder Robert Nicholas who focused on creating a park that was suitable for people of all walks of life and ages by building three small mounds, curved seating nooks, a wooden adventure playground, a stage and a petanque court. The area around the fountain was also opened up to create a large central plaza (Folpe).

All of these factors set the scene for a Washington Square park similar to the one that Patti Smith first encounters on arriving to New York. With new renovations and the long rich history of the park, it is easy to see why people of all walks of life would come to Washington Square Park. In a sense, the park serves as a stage for the entire city. Even though some might come to the park just for leisure it is expected that one will encounter someone doing something, whether it be a protester, a leafleter or an artist. In going to the park, one engages in this performance as either an audience member or a performer. In addition, even though time may change, the stage remains fairly the same as one could imagine the presence of those that came before like how Smith feels Henry James’ presence. In entering the park, one engages in this public interaction in one form or the other and contributes to the collective social climate and history of park. This collective history and narrative is interesting when thinking about New York in general as so many people’s paths are connected, merging and diverging constantly. However, this collective history is even amplified to its fullest extent when thinking about Washington Square park, an essential location for people of all walks of life to gather and experience the theatrics of everyday life in New York City.