Company and individuality were two very important themes in Patti Smith’s journey with Robert Mapplethorpe. Although these two notions seemed to be at heads with each other, since one would suppose that one can only find individuality through lonely reflection and conversation with the self, for Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe, they relied not on themselves but on each other for self-identification.

The idea of staying together until they had found themselves was first introduced when Patti Smith, coming back to New York from her short trip to Paris, found Robert weak and in need of medical treatment. They “promised that [they’d] never leave one another again, until [they] both knew [they] were ready to stand on [their] own” (88), just like how earlier they had vowed that one would always stay sober while the other was high. We readers can view the “Chelsea Hotel” chapter as a period of change, as a period when Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe gradually discovered their true calling and went on their separate paths. For Patti Smith, Chelsea Hotel had always been the location that she held dear in her heart: it was where she found her passion for performance through the encouragement of fellow artists. For Robert Mapplethorpe, the art crowd was also vital to

his personal growth as an artist: he got his first camera here and thus began his journey as a photographer.

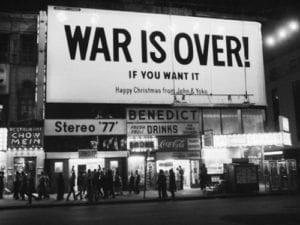

In the episode at the Times Square, we see the growing difference between the two: Smith and Mapplethorpe, viewing the same object – Lennon and Oko’s peace proclamation – conceived completely different ideas. For Robert, “it was the medium that mattered”, the medium being the Times Square billboards. They represented to him a signature of worldwide recognition, of fame, of wealth, of status, of becoming an Andy Warhol figure who “mirrored” the times. For Patti, such mirroring was not enough. She disliked Andy Warhol as she saw photographs mainly as a vague attempt to replicate life yet she wanted to be life. In some ways, she could relate more to the humanistic message this poster represented than Robert could, as she had always had a harder time grappling with losses (she always mourned the death of rock stars and kept connecting one with the other), so she rejoiced upon seeing this declaration. To her, having Lennon and Yoko – the poster-child of anti-war sentiment and peaceful activism – declare “war is over” was probably a huge consolation, not just within the context of war, but also on personal levels as well: it was a proof that showed maybe losses can be retrieved and pains could be somehow soothed and assuaged.

For Robert, there was so much more to success than money or reputation. What valued to him was recognition, recognition of him as an artist, but more importantly, an individual, which was vital to not get classified into the stereotypes: the junkie gay artist who shoots up and hustles at night. We see his resistance against types early on in the book: in the world of the others, he was gay; but for himself, homosexuality and heterosexuality coexisted and he was late to acknowledge his homosexuality. He never identified himself by any categorical name, and by that action, no categorical name ever defined him: there was a spontaneity to his way of doing things that was much like Patti Smith: they completely disregarded the society’s gaze and simply followed the most straightforward rule – the insolent will of heart. Robert’s hustling never made him a “hustler”, his homosexuality never made him a “gay”, his use of drugs and speed never made him a “junkie”: he was Robert Mapplethorpe and that was all. What he wished to achieve through fame was to try to make the world look at him through his friends’ eyes and acknowledge his existence as a peculiar individual, which can only be done through a certain degree of respect and critical acclaim.

That being said, it’s worth noting that none of them seemed to be particularly taken by the anti-war sentiment of the billboard. They were inspired, touched, yes, but they didn’t rally or get politically engaged. Ultimately, this is not a biography of an activist, but the journal of an artist who reflects and not acts, which may seem selfish but is nevertheless fitting of the theme of the book. The outside world mattered because it was through these events that they saw the world and found their voice: it was only constructive in their tireless search for personal identity, and this was what the entire book came down to: a quest for individuality.