Amid staffing challenges, Detroit is reimagining its beleaguered bus system while its suburbs risk allowing transit to languish

The city of Detroit and its surrounding suburbs are headed in opposite directions on bus transit. At the root of the issue: labor and leadership. Despite persistent staffing challenges, leaders in Detroit are showing increased willingness to support transit service improvements. In the suburbs, new transit leaders are instead stalling at the bargaining table with workers. In both city and suburbs, elected officials must lead by working with agency managers while demanding good transit service.

Public transit continues to face serious challenges and an uncertain future in the Detroit metropolitan area, including a shortage of drivers, unreliable service, and a lack of funding. Although nearly a quarter of Detroit’s 632,464 residents do not own cars and most of the region’s jobs lie in the suburbs, the region spends only about $80 per person per year on transit – among the lowest in the nation.

Bus service in particular is fraught. The Detroit Department of Transportation (DDOT) provides bus service within the city of Detroit and some inner suburbs while the Suburban Mobility Authority for Regional Transportation (SMART) serves the sprawling suburbs. That bus service has become far less frequent and reliable in recent years as DDOT and SMART drastically cut bus service due to the COVID pandemic, which never returned to original levels. In the city and suburbs, transit agencies provide an essential service to a mostly Black and working class ridership.

Low DDOT Wages Fail to Attract Needed Drivers

Transit advocates consistently identify the main cause: a shortage of bus drivers. The pay and working conditions are not competitive with other jobs that require commercial driver’s licenses. A bus driver at DDOT starts at a wage of $14.70 an hour. Meanwhile, neighboring Ann Arbor, which has fully restored its bus service to pre-pandemic levels, starts its bus drivers at $28 an hour. As long as wages remain low, DDOT will struggle to attract and retain bus drivers.

Without enough drivers, metro Detroit transit is in crisis. Bus riders consistently report delays or canceled trips. Riders sometimes see multiple missed runs, leaving them waiting two or three hours for a bus. Faced with unreliable bus service, low-income riders are sometimes forced to call expensive Uber rides to get to work on time – or lose out on job opportunities. The agencies’ crisis responses show that although much work remains to be done, the city of Detroit at least has a glimmer of hope for transit recovery.

The city of Detroit, which directly administers DDOT, has begun to address the bus driver shortage. Detroit closed out 2022 with a controversy over the selection of a contractor for DDOT’s troubled paratransit system, which led the federal government to threaten to withdraw funding. As service deteriorated and scandals piled up, Mayor Mike Duggan has devoted more attention to transit. In his 2023 budget proposal, Duggan asked for a $15 million increase for DDOT. Although transit advocates welcomed the increase, they argue that it’s not enough. Instead, they are asking for an additional $80 million, bringing Detroit’s transit funding close to its pre-bankruptcy levels in 2013.

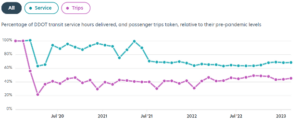

For its part, DDOT has been relatively transparent about its bad service. It publishes a monthly performance dashboard, which shows that while only 66% of its buses were on time, it has been able to run most of its scheduled service. It has begun restoring frequent service on its busiest routes by rearranging work schedules and offering more overtime. But DDOT can barely hire enough to keep up with driver attrition.

That hasn’t stopped it from dreaming big. In late April DDOT announced an ambitious plan to modernize its bus network and greatly expand service. The “DDOT Reimagined” proposal would increase frequency on routes across the city and speed up buses through measures like signal priority and bus lanes. DDOT would also expand its reach to inner suburban factories, warehouses, and shopping centers, much to the chagrin of some of some suburban leaders.

DDOT Reimagined is a solid vision that increases bus service, adjusts routes to match Detroit’s population trends, and improves access to suburban jobs. However, it lacks key details like operating cost and time frame. The plan’s scope and ambition is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it could inspire elected leaders to rally around a clear vision and raise funding. The new Democratic majority in Lansing is reportedly considering increasing transit operating funds in the upcoming state budget. On the other hand, DDOT could erode confidence by overpromising while failing to provide basic service. To move forward, DDOT needs to expand its public outreach and set clear expectations. DDOT Reimagined will require new funding and time to hire drivers, buy buses, and build infrastructure.

Detroit’s elected leaders finally agree that DDOT needs more support. DDOT, in turn, must use this chance to prove that it can run competently and carry out its ambitious expansion plan. Although DDOT’s drivers are in the middle of a labor contract, it doesn’t prevent the agency from offering a raise to attract and retain workers. The Detroit City Council, which approves the mayor’s budget, has proposed a competitive driver wage of $29 an hour. After decades of decline, residents could slowly be trickling back into Detroit. The city needs fast, frequent, and reliable transit to meet residents’ transportation needs and sustain its fragile recovery.

Labor Battles Hold Up Progress on Suburban Bus Service

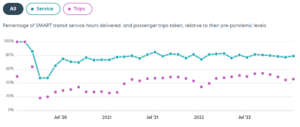

While Detroit offers a glimmer of hope, the path forward appears far more difficult for suburban transit. SMART bus service remains unreliable and infrequent, but no clear solutions have emerged. New management at SMART has a questionable track record with labor, and there’s little sign of progress.

SMART drivers have been working without a contract since February. Yet there has been no public word about contract negotiations or a much-needed wage increase – SMART drivers start at only $16.50 an hour. Perversely, transit advocates celebrated when SMART finally acknowledged the severity of its staffing issues and slashed its schedules in April to match the level of service it could realistically deliver. Although riders report that reliability has improved, the bad service means that SMART remains unviable even for many low-income commuters.

SMART’s public communications in response to the crisis have been poor. Unlike DDOT, SMART does not publish a performance dashboard. After a large group of advocates made public comments at a SMART board meeting in February demanding a new contract, SMART removed the option to attend meetings via teleconference. It abruptly canceled what was to be its first in-person only board meeting in late April. In response to public pressure, SMART management seems to be missing in action.

It’s unclear whether it can resolve this crisis alone. General Manager Dwight Ferrell, who joined in 2021, has a poor record in labor negotiations. Before joining SMART, he served as manager of Cininnati’s bus system. His tenure was plagued by poor relations with the bus drivers’ union amid attempts to replace bus routes with vans driven by lower-wage workers, leading to a vote of no confidence and threats of a strike. Previously, he was fired as manager of Fulton County, Georgia in 2014 due to conflicts with the county employees’ union. To survive, SMART must skillfully negotiate, offer competitive wages, and fully commit to providing reliable bus service. Instead, Ferrell prefers to talk about expansions of SMART’s Flex rideshare program, which uses vans driven by non-union gig workers.

There’s no question that SMART operates in difficult territory for transit. The suburbs of Detroit are typically low-density and car oriented. Conservative suburban officials have long been hostile to public transportation or any closer links with majority-Black Detroit. SMART was born out of multiple failed attempts to fund a regionwide transit system, derailed by the political, economic, and racial chasm between Detroit and the majority-white suburbs. It was not set up for success – municipalities were allowed to freely opt out of SMART, which many did upon its creation. Even with a liberal political shift, an increasingly diverse electorate, and a growing interest in high-density housing, SMART remains ill-equipped to take advantage of these positive trends.

But SMART does have a fresh wave of support. Voters in suburban Oakland County ratified the system’s expansion in November 2022 into populous and job-rich suburbs that once opted out. However, it’s unclear how SMART will add new routes by this summer as planned if it struggles to run its current service. Little public engagement has occurred since the election. If SMART does not solve the driver shortage soon, it could burn through the support that voters demonstrated. It needs to take drastic action by focusing on the basics: provide high quality transit and actively engage with the public.

Just as with DDOT, elected officials choose the leaders, control the funding, and bear the ultimate responsibility for SMART. The executives of each suburban county appoint SMART’s board members. Oakland County Executive David Coulter and other county officials approved and campaigned for last year’s transit expansion, an explicit repudiation of the county’s longtime hostility to transit. If suburban politicians are serious about making progress, they need to continue their support beyond the election by taking an active role in solving the driver shortage and implementing the service expansion.

The history of transit in southeast Michigan unfolds as a decades-long tragedy. The region failed time and time again to raise funding, doubling down on urban decay and white flight. Michigan’s transportation policy has long favored automobiles and highways to the exclusion of all else. But in the Motor City, people need public transit and will ride a service that is useful. Opportunities abound for improving service and providing critical transportation to those who rely on it. By increasing funding, increasing driver pay, and engaging with the public, elected officials and agency managers must work together to improve transit and ensure that riders have access to the opportunities they need to thrive.