Legislators ought to support the proposal, rather than water it down, and actually tackle the housing crisis

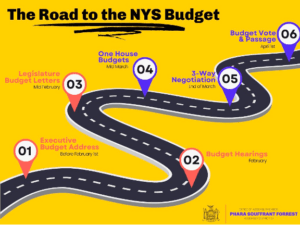

New York governor Kathy Hochul’s ambitious “New York Housing Compact” proposal is at risk of being gutted during the state budget negotiation process. Earlier this month, the New York State Assembly and Senate each released their own budget proposals, both of which would not include some of the governor’s most important provisions for housing production targets and transit-oriented development (TOD). State law requires the governor and legislature to agree on a single budget by April. Between now and then, the governor and legislature must negotiate, vote, and sign a single budget document. On housing, the governor’s proposals are transformative for struggling New Yorkers, while the legislature’s will do little to change the housing crisis status quo.

Governor Hochul unveiled the Compact, a package of reforms to build 800,000 new homes over the next decade, in February. The plan takes some of the most ambitious reforms recently proposed or passed in other states and applies them to New York, where rents and home prices continue to spiral out of control. They’d require every part of downstate New York – including the wealthiest areas of New York City, Long Island, and Westchester – to build enough housing to welcome residents and relieve pressure on existing residents. But the Assembly and Senate’s own budget proposals, each released in mid-March, would replace the Compact’s sticks with carrots, removing the the governor’s proposed enforcement mechanisms and replacing them with voluntary incentives.

Sadly, cutting critical housing affordability efforts from the budget is nothing new. About a year ago, the governor proposed some reforms that were actually less ambitious than those she’s proposing now for the 2023 budget. But she had to reverse course – backing away from a proposal to legalize ADUs statewide, thanks to swift bipartisan opposition from NIMBY suburban legislators. Three other important supplementary housing policies are also at-risk this cycle, including eliminating the state’s floor area ratio limit for residential development, bringing back the 421-a tax incentive for income-restricted affordable housing, and legalizing ADUs New York City-wide. All three would complement the housing compact’s goals by permitting taller city apartments than currently allowed, incentivizing developers to include affordable housing in their projects, and legalizing more and more kinds of housing options respectively.

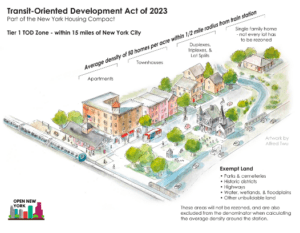

The Compact has two key components: housing production targets and TOD standards.

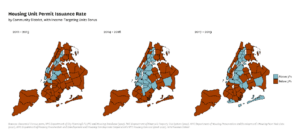

Each New York City community board and all other downstate localities would be required to meet a housing production target, growing their housing stock by three percent every three years under the governor’s plan. Upstate localities would be required to grow by one percent every three years. Income-restricted housing units would count double toward the target.

If a locality fails to meet its targets, the state can trigger a process known as the “builder’s remedy” that allows developments to go forward with state, rather than local, approval – that’s the “stick”. Both the Assembly and Senate’s proposals would remove the builder’s remedy, instead offering $500 million – the “carrot” – to localities that voluntarily reach those three or one percent housing production targets. But enforcement is critical to actually getting the 800,000 units built. As California housing advocate Jordan Grimes put it, his state “tried the carrot approach for years. It doesn’t work. Learn from our mistakes!” And the NYU Furman Center found similar voluntary efforts to upzone wealthy communities in Massachusetts and Connecticut were also ineffective.

Another Furman Center report notes that in a recent three year period most of New York City’s community boards, including most of Manhattan, southern Brooklyn, outer Queens, and all of Staten Island – some of the city’s wealthiest and least diverse neighborhoods – would have failed to meet the proposed targets. With carrots instead of sticks, it’s much less likely the wealthiest parts of New York City opt-in to the production targets in exchange for cash.

The governor was right to skip the ineffective opt-in step and move right to requirements. Legislators like Senate majority leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, who says “we can get there with incentives,” are kidding themselves if they think incentives will be any more effective in New York – they haven’t worked anywhere else.

In order to promote TOD, downstate localities would be required to amend local zoning laws to allow for a set level of homes per acre within a half mile of any year round rail station. Within fifteen miles of the New York City border, the minimum is an average of 50 homes per acre in that half mile radius, stepping down to lower levels further out. The budget would include $250 million toward infrastructure needed to support these new homes. But the Senate’s proposal would entirely remove the TOD rezoning requirements. Without the requirements, any new development near train stations in the region could be built far too small to significantly contribute to New York’s overall housing stock, creating less housing than needed at valuable sites for decades.

But a lot has changed in the past year – Hochul won her election, removing some political risk. Many of the Democratic legislators who opposed her plan lost, leaving her party’s caucus theoretically more united in support of housing reform overall. The housing crisis has only gotten more attention, with other states passing pro-housing laws and the Biden Administration strengthening fair housing regulations. And as I argued last year, it’s becoming clearer that boosting housing production is a political imperative for federal and state Democrats. All of this should have made it easier to get ambitious reforms over the finish line and signed into law this year.

But there are still a lot of negotiations and opportunities to pressure legislators left before the budget is finalized at the start of next month. The Assembly and Senate budget proposals are just as much of a “starting point” as the governor’s – and the New York budget process generally gives the governor a lot of room to stick to proposals she cares most about. Let’s hope the legislature is just establishing a negotiating position, diluting the Compact’s best provisions in order to get something else the governor isn’t otherwise inclined to support in the overall budget too.

The governor’s Housing Compact would be transformative. It would not only provide hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers with badly-needed relief from high housing costs over the next few years but demonstrate to the country that Democrats can deliver for their constituents – neutering the right-wing argument that liberal states are dysfunctional and unaffordable. Despite the usual outsized protestations from suburban NIMBYs, the governor’s proposals are popular – 67 percent of New Yorkers support legislation that promotes TOD. Even Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone, representing often reluctant-to-build Long Island, recognizes her plan would benefit all New Yorkers, calling it “a comprehensive, multifaceted proposal… to help build a livable & sustainable economic future for Long Island.” State legislators should recognize the opportunity they have to make their own communities, their state, and the country more prosperous.

If you live in New York State, call your legislators and tell them to support the Housing Compact in full.

You can reach the author of this piece, Andrew DeFrank, at: defrank@nyu.edu

You can reach the editor of this piece, Patrick Spauster, at: ps4375@nyu.edu