Affordable homes have fewer bedrooms than New Yorkers need

This past summer when preparing to make the move from Texas to New York City, three potential roommates and I began looking for affordably-priced, market-rate, four-bedroom apartments.

We began our search with the thought that ‘the more, the merrier,’ but our hope to decrease our individual rent amount through a big group size while having enough space to ourselves was quickly crushed. As August approached without a signed lease to show for it, we became frantic and panicked as our deadline to move grew closer. Among the many barriers we faced was the fact that four-bedroom apartments were hard to find. Our friends told us to decrease our group size.

We had the flexibility to go down a member. But what about the families in New York City without that luxury? Were we just unlucky, or was it really that hard to find an affordable unit with more than three bedrooms? Was this phenomenon the same for income-restricted affordable units? What kind of trade-offs are low-income housing-seekers facing in their search for privacy, comfort, and shelter?

New York’s new affordable units are disproportionately smaller

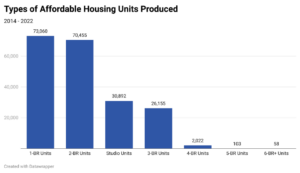

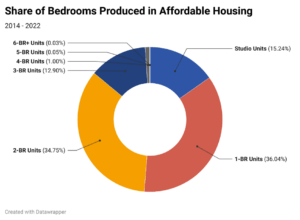

According to data from the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), NYC has produced more studio, one-, two-, and three-bedroom units individually than four-, five-, six-, and up-bedroom units combined since 2014. The highest unit production was for one-bedroom units, with two bedrooms being a close second. Studios were the third highest in production with approximately 40,000 fewer units than two-bedroom units. Three-bedroom units were close behind in fourth. However, there was another huge gap in production between three- and four-bedroom units (approximately 24,000 units less than three bedrooms).

Studio, one-, two-, and three-bedroom units account for approximately 98.9 percent of all affordable housing production since 2014. For a family with more than two children, this presents a problem. While these numbers do not account for affordable units produced prior to 2014 that are still on the market, they do showcase a trend in production that may become an issue as the housing stock ages and is replaced accordingly.

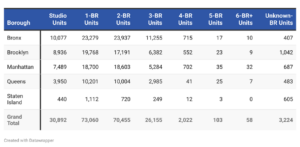

When looking at a breakdown by borough, the Bronx led in affordable housing production for studio, one-, two-, three-, and four- bedroom units. Manhattan was the leader in five-, six- and up bedroom units. But is the distribution of units by borough and if congruent with their average family size?

NYC’s affordable units are too small for NYC’s families

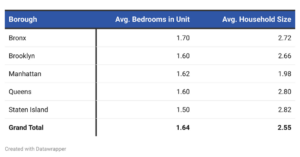

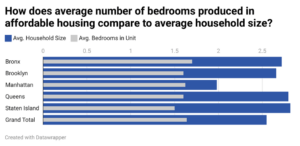

According to data on family size from the NYC Population FactFinder, the number of bedrooms in new units lag behind the average household size.

I expected the average number of bedrooms in units produced to be low given the amount of one- and two-bedroom units produced; however, I did not expect the averages to be so low in comparison to the average household size. Manhattan had the lowest difference of 0.36, while Staten Island had the biggest difference of 1.32. Every borough produced units that had fewer bedrooms than the average household size would require for each resident to have their own room.

In order for each family member to have a private room, affordable housing developers would have to, on average, add at least one bedroom to their units in production to stay consistent with the average household size. While the extra room can be negated in some cases due to a two-parent household where the parents share a bedroom, approximately 250,000 households in NYC have single-parents.

The problem may not just be developers, however. The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) provides a breakdown for how many bedrooms are given depending on household breakdown. But basically any family with children needs at least two bedrooms by those standards, and there aren’t enough family-size units to go around. If families have two children of the same gender or there is a single parent with a child that shares a gender with them, it is often assumed that they will share a room with each other. For example, a family of one mother, two daughters, and a son are assigned the bedroom size of three. Therefore, a private bedroom is seen as a luxury in affordable housing development and it appears housing is not constructed with the average family size in mind — at least not in the sense that everyone can have their own space.

. . .

Household size may be changing – but NYC still isn’t keeping up

The issue that the bedroom-to-household-resident ratio presents depends on trends in household size and composition, the unit size in the existing housing stock, and future building patterns.

For some families in a two-parent household, the difference between the bedrooms provided and the household size might not matter as much. Additionally, culture, trends in childbirth, and demographic shifts may reduce the need for more bedrooms. For instance, in some cultures, it is normal to share a room with your siblings. In others, it may not be perceived as an issue as children may be expected to leave the house at the age of 18, and room-sharing is thus seen as temporary. The trend of people having fewer or no children may sway production trends. Or the aging population in NYC may prefer these smaller units.

The city and researchers would be wise to consider these trends when making decisions on what to build and where. Recently, New York City published its initial findings for the 2021 Housing and Vacancy Survey, which included statistics that showed housing production has been decreasing since 1947 — presumably because space is becoming more limited. In data published by Baruch College, the average number of persons per household has fluctuated year-to-year. Understanding the current housing stock will help New York City better plan for the future.

Ultimately, it may be true that four-bedroom units are hard to find in New York City, so my roommates and I made the right decision of splitting to make our housing search easier. If you find yourself in a similar position, just know that the more of you there are, the more barriers there might be.