Over the course of the COVID pandemic, frontline workers–nurses, doctors, grocery store clerks, waitstaff–garnered the nation’s respect and gratitude to help the rest of us stay safe at home. Although eating establishments eventually reopened across the country, indenser cities like New York, there was a boom in demand for food delivery, highlighting just how essential food delivery drivers have become.

Delivery riders have become increasingly common in recent years, and central to many restaurant operations, but they have faced adversity from all sides, often with little capacity for recourse. The throttled electric bikes that many delivery riders use were illegal in NYC until November 2020. Delivery riders were unfairly targeted by this law, and the police, who fined riders and often confiscated bikes. As food deliveries become more common, riders are being targeted by bike thiefs, often being set up according to the NYPD. On March 29th, 2021, a 29 year old delivery rider named Francisco Villalva Vitinio was shot and killed in East Harlem after refusing to give up his electric bike.

Delivery riders are also often disregarded by restaurants, and not allowed to use the bathrooms. Additionally, delivering can simply be dangerous. Riding on the roads in New York City for hours each day, often unprotected from cars and trucks, can prove to be deadly. Two delivery riders, Ernesto Guzman, and Alfredo Cabrera Licona, were killed by drivers in November. In addition to these challenges, riders are often at odds with the companies that run the delivery apps themselves.

Image 1: Edgar Sapon (Source: The New York Times)

Image 1: Edgar Sapon (Source: The New York Times)

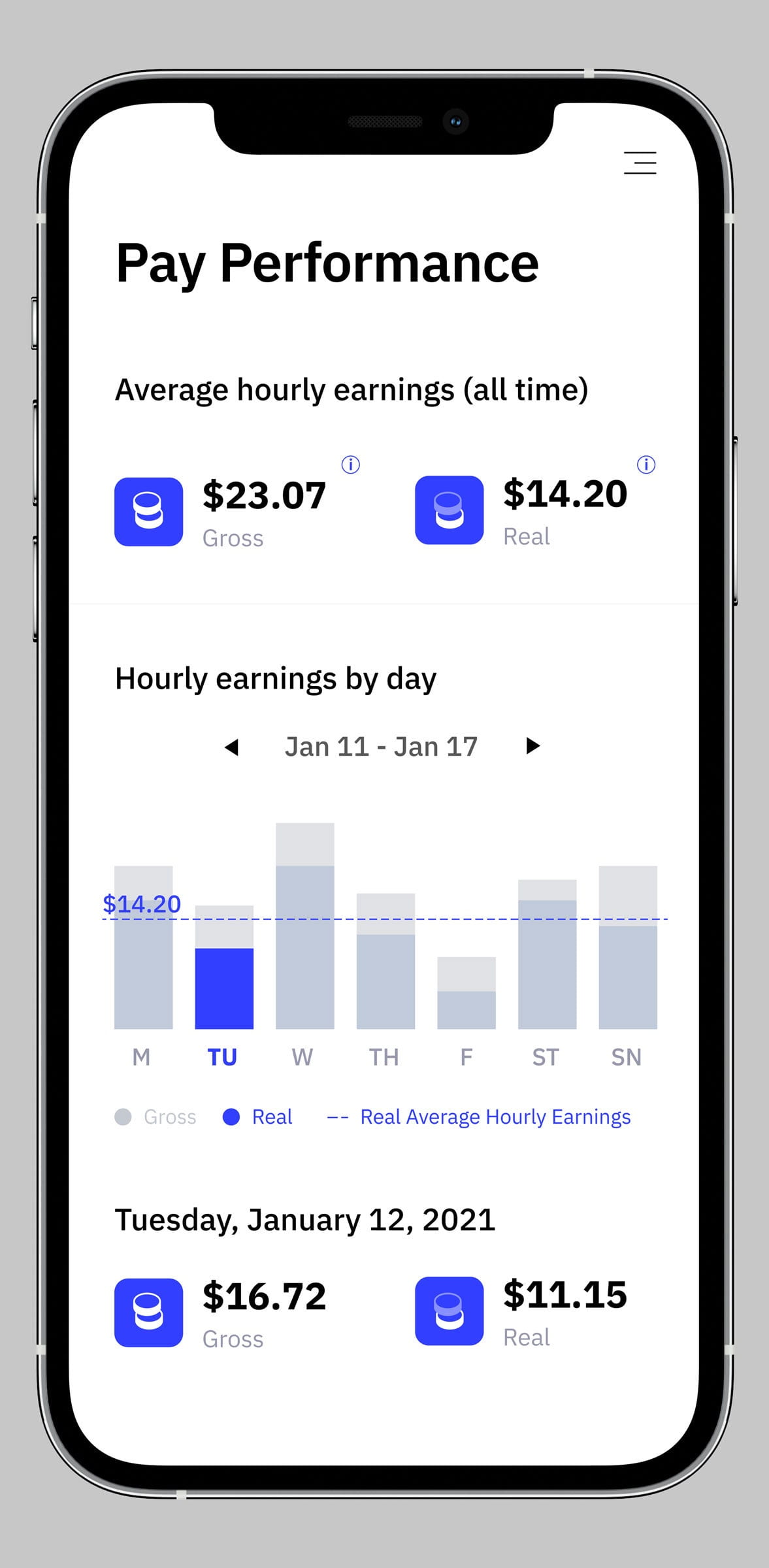

Gig workers face fiscal hazards stemming from company behavior, and poorly or deceitfully designed algorithms. The large companies that run the delivery apps such as Uber Eats, DoorDash, Caviar, Postmates, and Relay have been known to withhold tips and wages from workers. To begin with, as independent workers their pay may be inconsistent. On a good day a rider may earn $100. Doordash settled with the DC Attorney General for $2.5 million after siphoning tips from delivery workers. Relay, a mostly NYC-based company has been the subject of a number of lawsuits alleging they withheld wages. Numerous apps also may produce occasional pay discrepancies because of how the algorithm calculates wages. This has led some gig workers to create digital tools to help others keep track of wages independent of the algorithms delivery and gig work companies have created.

Driver’s Seat Cooperative, launched in 2019, and owned by the gig workers who join the cooperative, helps workers collect and analyze their own data from ride-share and delivery apps. So far, over 600 workers in 40 cities have joined the cooperative, which, with pooled data from workers helps them decide where, when, and which app to sign onto to make the most money. The app also keeps track of money made after expenses. Driver’s Seat Collective hopes to sell this data to city governments and transportation agencies wanting to learn more about gig work, and share the profits with cooperative members. This not only gives workers access, but ownership of the data they create as well. The app would also give public authorities the chance to examine data on gig work that they otherwise cannot gather.

Cities gather many types of data regarding transportation. For example, the NYC Department of Transportation (DOT) gathers all sorts of data on vehicle speeds, traffic, bicycle counts, bus stops, and even street pavement quality. However, no matter how much the DOT might want to collect data on rideshare and food delivery, such data is held by private companies. While Driver’s Seat Collective is still new and has relatively few members, its potential is great.

San Francisco has already taken advantage of the app’s access to gig worker data. In a recent study on ride-hailing and delivery workers, San Francisco included trip and earnings data generated by Driver’s Seat Collective, which complemented data from in-depth surveys conducted by the Institute for Social Transformation at UC Santa Cruz. The study aimed at creating a representative sample of on-demand work being done in San Francisco mainly for understanding labor practices, and developing labor market policy. The data collected can show:

- Ratio of paid to unpaid work time

- Driver total and average number of hours worked

- Driver gross earnings

- Driver mileage-based expenses

- Geographic and temporal distribution of where the work happens, including how much work is performed with in SF City/County limits

This data can be segmented by time, day, and geography, and analyzed by distance and time. Used in conjunction with extensive survey data, the study shows that gig work in San Francisco is predominantly used as full-time work, and consists mainly of immigrants and people of color who often struggle to make ends meet, particularly during COVID. Many workers end up making less than San Francisco’s minimum wage, which is $15.59/ hour. These workers also do not receive benefits because they are not classified as employees. The study pushes for policy that enforces city and state employment laws for this workforce, as well as policy that addresses the economic, safety and health, and public health concerns facing this workforce.

Image 3: Natanael Evangelista (Source: The New York Times)

Image 3: Natanael Evangelista (Source: The New York Times)

This approach could prove useful to cities across the US that have undoubtedly experienced an increase in ride share and food delivery workers during the pandemic. Not only has the pandemic proven just how important these workers are in helping to maintain public health measures while supporting local economies, but it has also further exposed how vulnerable these workers are. They are vulnerable as individuals in their environments – to thiefs, automobiles, and discriminatory laws and establishments. They are also vulnerable to the companies that control their work and obscure their information.

At the moment, New York City doesn’t seem to have much data on one of its most vulnerable workforce. It is easy to imagine how few cities might actually have survey data on the delivery rider workforce. Cities and states are obligated to better understand gig work and those who do it because of their vulnerability and value to local economies. Those same cities and states should consider using extremely valuable data from Driver’s Seat Collective to further that understanding, and take action to protect some of our most essential workers.

Cover Image Source: Gustavo Ajche (The New York Times)