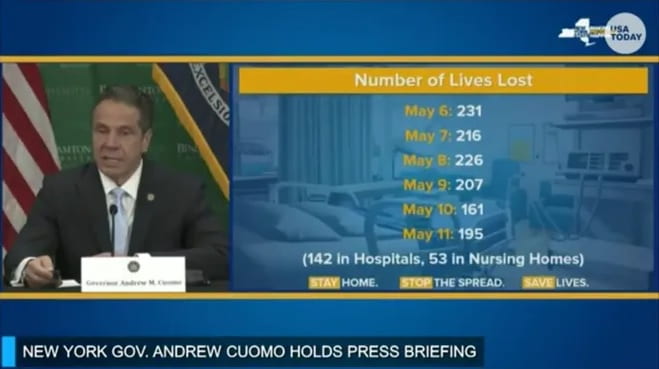

The COVID-19 pandemic has irrevocably changed New Yorkers. New York City residents were glued to their TV and computer screens anxiously awaiting information in early March 2020, as the City became an early epicenter of the virus. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo rose to the occasion and began his Emmy award-winning daily briefings that informed not only New Yorkers of the COVID-19 updates but quickly encapsulated the world’s attention. After the publication of his book about the handling and leadership of the initial COVID-19 approach in October 2020 – the icon of the “New York Tough” attitude – his reputation quickly declined. It was recently discovered that Governor Cuomo used his powers to protect his largest political donors from the legal consequences of 15,000 nursing home residents COVID-19 related deaths and delayed the release of the data.

Now, among calls to strip Cuomo of his emergency powers, New Yorkers demand more data transparency. With a 215% increase in time spent online on mobile devices accessing news alerts from March 2019 to March 2020, everyday citizens have become more obsessed with keeping up-to-date with the news – notably, data surrounding the spread of COVID-19. The combination of increased news consumption and the current New York State data scandal makes it even more important to understand why an equity-lens must be incorporated into the existing data collection. As a society, we have become enamored with the idea of data informing our policy decisions, but what if data doesn’t capture the complete picture?

Both 2020 and 2021 have been the most unprecedented years of the 21st century. Local governments have been forced to react quickly to control spiraling situations, which hasn’t permitted accurate or extensive data collection to take place. The data that has been mostly collected and consistently repeated across the mainstream news media outlets- such as MSNBC, Fox, CNN, and CBS- have been the rate of COVID-19 infections, death rates, the emerging strains of the virus, vaccination sites, and the occasional sprinkle of disaggregated data.

Image Source: The Daily News

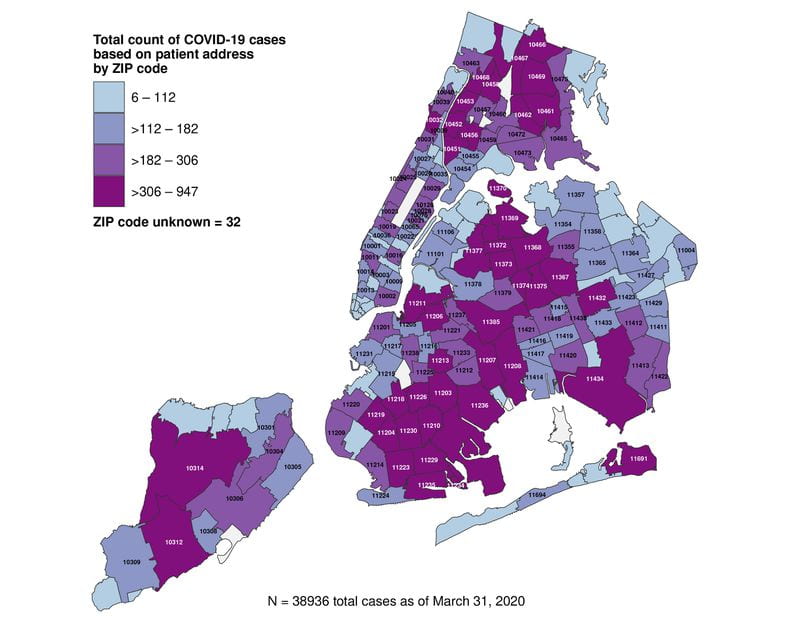

Image Source: The Daily News

On March 31st, 2020, the most COVID-19 cases map shook New Yorkers to their core. For some, it was the beginning of their racial reckoning or the realization of the inadequate distribution of resources throughout the City. But, the story cannot end here, nor can the data collection. Recovery efforts began in summer 2020, starting with small business revitalization programs- such as COVID-19 business loans and assistance, the Open Streets initiative, and the Open Storefronts program– and have saved countless small businesses. On the flipside, policymakers must think critically about companies that did not qualify for government assistance. Firstly, look into why businesses were deemed ineligible and find ways to amend future policies to be more inclusive of those businesses. Secondly, all government levels must assist small businesses in the recovery efforts to even out the playing field with companies who were eligible and received assistance.

The Coronavirus has shown us global disparities (Great Divide), but little data collection has allowed for a more nuanced understanding of how this came to be. The pandemic has disproportionately impacted Black, Indigenous, and communities of color- this has been the mainstream media narrative that has been consistently drilled into our minds since the beginning. However, policymakers and planners have the grave responsibility to understand that numerical data cannot compensate for cultural understanding vital to inform an equitable recovery. For example, according to the Pew Research Center, 64 million Americans live in multigenerational households, with Asians and Hispanics holding the highest percentage. A few questions that come to mind include, but not limited to-

- How has the pandemic impacted intergenerational households?

- How many intergenerational households have frontline workers as heads of households?

- How many children have had to become caretakers for both younger children and elders while managing school and other responsibilities?

We must ask ourselves these detailed questions because they can inform policymakers and planners of the potential missing data. More importantly, it gives planners the opportunities to collect data that allows for a more holistic understanding of the present moment. If planners can grasp what the most affected and marginalized populations are experiencing, then we can plan accordingly to ensure that these needs are met for an equitable recovery. But to understand the most vulnerable housing needs, especially as profoundly as it demands it to be, frequently comes from those who have experienced the current housing system’s failures or how in various ways that policies haven’t thought about them. In other words, the ability to capture more detailed information requires diverse socioeconomic analysts at the forefront of data collection and planning efforts. For example, planners can advocate for more daycare centers or retirement homes for neighborhoods with many multigenerational households, or perhaps for more healthcare resources to mend the vast borough inequality. More importantly, we can plan for a people-centric city to make places more livable for them rather than cater to big tech companies like Amazon or Google in traditionally residential areas. Data and other empirical pieces of evidence will validate the truth and detrimental need for more people-centric policies. We have to take advantage of the present moment to begin more holistic data collection processes to inform a more equitable path forward.

New Yorkers will build back New York- with planners, policymakers, and engineers at the forefront of it all. Recovery efforts will be informed by the present-day data collection, making it even more necessary to capture the class divide’s nuanced COVID-19 realities among New Yorkers. Suppose data begins to be viewed as a pillar towards recovery. In that case, collectively, the preparation for an equitable recovery will be fairer and more honest, leading to more inclusive and original policies.

Cover Image Source: Press Connects