The promises and peril for transit expansion in Puerto Rico

Photo by: Gian Cordero

Photo by: Gian Cordero

Last month in San Juan, after a week of free service, the Director of the Integrated Transit Authority of Puerto Rico (ATI) announced that the system saw a 26% increase in patronage, demonstrating that when the public perceives a public transit system as more convenient than personal vehicles for reaching destinations, they are inclined to use it. This phenomenon mirrors the heightened ridership experienced during events such as the Calle San Sebastian Festivities and activities hosted at the Choli (Puerto Rico’s primary arena), which generate significant and unusual patronage for the Tren Urbano (San Juan’s metro). However, despite these encouraging signs, the reality remains that our mass transit system presents numerous challenges for users including limited destinations, weekend service gaps, insufficient frequencies on most bus routes, and a lack of transit-oriented developments around stations. While efforts are underway to address some of these issues, some are being overlooked entirely, and others demand further analysis and innovative solutions.

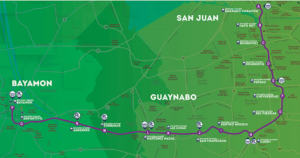

The Tren Urbano is the second newest metro system in the United States (only behind the Skyline in Honolulu), and runs through the municipalities of San Juan, Guaynabo and Bayamón in the metropolitan area of the capital city. The system is incomplete, with only one of the originally planned four phases finalized. Proposed routes to key locations such as the International Airport, Old San Juan, and the densely populated areas of Santurce remain unbuilt. This shortfall can largely be attributed to two primary factors. Firstly, in 2006, shortly after the metro’s inauguration in 2004, Puerto Rico grappled with a fiscal crisis that precipitated a government shutdown. Secondly, the projected cost of the Tren Urbano surged by almost 150%, escalating from $800 million to $2.3 billion. Plans to build out the full system were officially scrapped in 2012 and no extensions have been built since the opening of the first line.

Delays and cost increases for large infrastructure projects are not unique to Puerto Rico. In fact, it could be argued that this is a problem that the colony inherited from the United States, where cost increases and delays are the order of the day for major infrastructure projects ranging from road construction to modernization of mass transit systems. A prime example is New York City’s Second Avenue Subway expansion project. Initially proposed in the 1920s, the project suffered numerous delays and cost increases over the years. Its first phase, which opened in 2017, cost approximately $4.5 billion, far beyond initial estimates. Cost increases and delays are often the result of a combination of complex factors. First, the very nature of large-scale infrastructure projects carries a variety of inherent risks, from land acquisition and expropriation to contract management and the coordination of multiple stakeholders and different levels of government. In addition, changes in political priorities and funding allocations can affect the continuity of funding needed to complete projects on schedule. Also, the need to comply with regulatory and environmental standards set by the federal government, as well as the influx of lawsuits (or threats of) from disgruntled citizens, can lengthen lead times and increase operating costs. While environmental regulations and safety standards are essential, they underscore the challenges Puerto Rico faces within the colonial framework, navigating federal laws and policies that hinder local development and bureaucratize infrastructure projects.

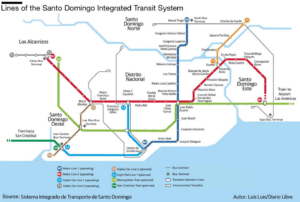

A good way to look at this would be to contrast Puerto Rico with the neighboring Dominican Republic, with which it probably shares more similarities both physically and socially than with any U.S. state. Currently, the city of Santo Domingo is seeing one of the largest mass transit transformations in the hemisphere. In September 2023, Dominican authorities announced a mega-project to expand the capital city’s integrated transportation system. This project would add two train lines, a light rail line, and a cable car line to the existing network of two metro and two cable car lines (the most modern urban cable cars in the world). This expansion is projected to cost $3.6 billion, a sum unimaginable for a project of similar scale within any U.S. territory, including Puerto Rico. For Yindhira Taveras Canela, engineer and professor at the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo, “In the United States it is a little different because there are more funds, Puerto Rico could really have a much more efficient system because it is not a question of funds as in the Dominican Republic.” She also highlights that “Puerto Rico has another advantage, and that is that they have many engineers studying at the University of Puerto Rico who are being underutilized or are leaving to the United States for better salaries. Puerto Rico has everything to get ahead in terms of transit projects and could even provide an incentive for more young people to study and stay working on their developments.”

Unlike Santo Domingo’s growing rail network, San Juan’s rapid transit system has stagnated due to escalating costs and Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis. (Tren Urbano map from ATI)

Beyond the financial and logistical challenges, Puerto Rico grapples with ingrained planning and land use practices mirroring those historically employed in the United States, from the overuse of single-family residential zoning, to urban street designs centered around private vehicle reliance. This is related to the cultural aspect of how we prefer to inhabit cities. As in the United States, many people in Puerto Rico see the home with a two-car garage and a large backyard as synonymous with progress, ignoring the livability of public spaces in our cities. However, I think that idea is breaking down, especially among the younger generations. Gian Cordero, a high school student who has used his platforms to educate about and improve mass transit in Puerto Rico, says, “We young people want to explore our system, and we want to be part of it. The buses, and the Tren Urbano become part of our lives as we think about our future as citizens.”

Puerto Rico’s colonial status presents obstacles to the development of mass transit services on the island. However, cultural changes in terms of citizen behavior and attitudes towards transportation and the livability of public spaces present a unique opportunity to eliminate the inconveniences of the transportation system. Now is the time to learn from past mistakes, take advantage of present opportunities, and aspire to a future where dependence on the private automobile is not the norm in Puerto Rico. San Juan, like Santo Domingo, can set an example for the rest of the world.

You can reach the author of this piece, Gabriel Negrón Torres, at: gan9751@nyu.edu

You can reach the editor of this piece, Calley Wang, at: csw9856@nyu.edu