While evaluating corruption in India, one only focuses on the ways in which it inhibits growth. However, when looking at corruption at the local levels (local administration, city governments, municipal corporations, local development authorities), there should be more nuance and variation in one’s evaluation. By bringing together insights from Yuen Yuen Ang’s ‘China’s Gilded Age: The Paradox of Economic Boom and Vast Corruption’, Indian urban history and the recent urbanization boom, I aim to paint a more comprehensive picture. I will showcase the history of corruption, its prevalence in the growth of Indian cities, and its impacts on developing cities. This is not a justification for corruption in urban development, but an explanation of the cyclical systems it creates, and ways to legalize and regulate these illegal activities.

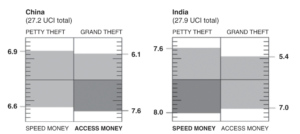

Yuen Yuen Ang’s (2020) China’s Gilded Age: The Paradox of Economic Boom and Vast Corruption discusses the puzzle of how China’s economy has boomed despite the rampant corruption that takes place at every level. Ang creates a framework explaining four types of corruption- Petty Theft, Grand Theft, Speed Money and Access Money. She equates Petty Theft and Grand Theft to toxic drugs, as they economically damage the public, subvert law and order, and deter investors, entrepreneurs and foreign aid donors (Ang, 2020). She contrasts these two types of theft with two types of “exchange corruption”, where both parties benefit. Speed Money refers to petty bribes paid to non-elite, low-level and local bureaucrats to circumvent the system, and Access Money refers to high stakes rewards offered by elite capital investors to powerful officials, in exchange for exclusive privileges (Ang, 2020). These distinctions can explain the uniquely convoluted story of corruption in Indian cities.

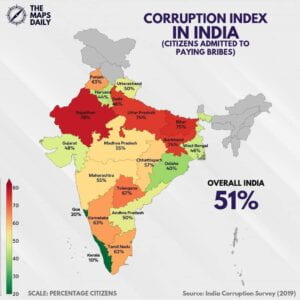

The Unbundled Corruption scores of China and India can be seen above. The dominance of Access Money is the mainstay of discussion in Ang’s analysis, where she discusses how Access Money in China stimulates business activity by benefiting both the politicians and businesses. Politicians are motivated to stimulate growth and take these payoffs while businesses are then allowed to invest and build more, increasing their market share. In India, Speed Money dominates because the majority of corruption comprises bribes to overcome administrative barriers. Chinese corruption is focused on lucrative, high risk and high reward business deals whereas Indian corruption is focused on greasing the wheels to make the system move faster and gain access to business permits. This difference is key, as it plays out in the economic growth stories of these two nations- China has had sustained GDP growth through big investments into all segments of its economy, whereas India has relied more heavily on rapid urban development to fuel its economic growth. Given India’s considerable Speed Money Corruption score as compared to China and other developing nations like Nigeria, Indonesia, and Brazil, I will focus on the impact of Speed Money on the growth of Indian cities.

The dominance of Speed Money can be explained by the system of checks and balances embedded in India’s fragmented democracy, where the veto power for each individual local bureaucrat is high (Ang, 2020). This practice began in post-independence India in 1951. The mix of a large decentralized democracy and the The Industries Act, which required all business operations to receive licenses from the government to function led to bribery in urban development being ubiquitous (Clark, 2021). This was called the License Permit Raj; in the name of creating a socialist system, local governments subtly encouraged bribery and rent-seeking behavior to circumvent the barriers they themselves had placed.

Post liberalization, urban development policy became developer centric due to the abolition of licensing activities. However, local agencies would still award operating and building permits while collecting bribes based on project size. This established a link between the size of the basket of corruption and the amount of infrastructure built (Pani, 2017). Administrative and discretionary powers lay with the city officials and bribes were given to several local bureaucrats. Their veto power allowed the real estate and urban development process to slow down, causing multiple delays due to red-tapism. Hence, petty bribes were paid by large scale developers to local politicians constantly to move this process along and get their building permits in place. Further barriers were placed upon these developers as bribes were also required for providing centralized connections to utilities like electricity, water, and sewage. On top of this, they are commonly paid out in cash, making them difficult for the government to report and track. This only promotes the practice of bribery and affirms its dominance in the system. Speed Money eventually became an essential part of urban development and is now perceived as a tax to be paid to speed up the process.

India’s urban development has been unplanned with corruption at the very heart of it. For the last 20 years, every major development project that has helped Indian cities grow has an element of corruption. The corruption comes in the form of Speed Money, which is why it is never caught but is always taken as accepted practice. The drawbacks of Speed Money are significant, and are compounded due to a lack of planned infrastructure development.

As the amount of corruption is directly linked to the amount of infrastructure being built, an urbanization boom in Indian cities has seen corruption in urban development skyrocket. The National Capital Region came to be the fastest growing region in the world, with the number of residential properties and their prices tripling and quadrupling in the last 10 years, respectively (Dharia, 2021). This pace of urbanization came with a subsequent increase in Speed Money infused into the system. The incentive to allow more infrastructure projects being built due to an increase in the size of the bribes led to large-scale privatized real-estate growth that was unchecked by local bureaucrats due to their kickbacks received. This resulted in urban areas emerging without adequate infrastructure in what was once forests and farmland, creating unconnected and deficient water, electricity, sewage, waste disposal, and sanitation systems (Dharia, 2021). To this day, sewage overflows into clogged water canals and causes regular flooding and sanitation issues for the urban population, posing serious health hazards.

Corruption has also created grave inequalities in cities, where luxurious apartments and office buildings overlook extremely dense urban villages underserved by the local bureaucrats. The urban village residents are migrant laborers who have moved to cities from their rural hinterlands in search of work opportunities, and work as domestic servants, taxi drivers, security guards, sanitation workers, and daily wage construction workers. The local bureaucrats ignore these areas as they do not add to their bribery coffers. The urban village residents cannot afford to bribe local bureaucrats to build better facilities. They bear the repercussions of the institutionalization of Speed Money, creating a poverty trap. On the one hand they are unable to pay bribes to develop their area; on the other hand they are unable to raise their incomes due to a lack of economic development opportunities coming from this inability to bribe.

However, there are some unintended benefits of working with corruption that can be looked at as a stimulus to growth. Speed Money has created a cyclical effect on urban development in India, through a series of linkages between corruption and urbanization. Initially, the established connection between Speed Money and infrastructural growth led to rapid urbanization. This urbanization created and expanded many urban regions, transforming sleepy towns into urban metropolises like Gurugram and Bangalore. The influx of population into cities from the rural hinterlands created an environment suited for business, entrepreneurship, and retail establishments as demand skyrocketed. Further infrastructure improvements led to increased Speed Money payments in the development of these cities, incentivizing local bureaucrats to promote even more urban development. With time, Gururgam and Bangalore became notable startup, technology and Foreign Direct Investment hubs. Hence, with the urbanization and further anticipated growth, more cities will be growing rapidly due to the presence of Speed Money and its facilitative effect on urban development from local bureaucrats.

The increase in Speed Money poses a significant issue on the misuse of funds as well, where the bribery constitutes a leakage from the urban development system. The funds misplaced on bribes for corrupt officials could otherwise have gone towards providing more comprehensive infrastructure, especially for the urban poor. By increasing their standard of living and providing them flood security, local governments could have also reduced spending on disaster relief and repairs. Hence, these leakages constitute a big loss to the local development framework.

The potential benefits of legalizing and regulating this local bureaucratic corruption are substantial. The money leaking from the system can be recycled through the form of a tax or allowance for local administration. This money can be earmarked for developing surrounding infrastructure and basic facilities, defined as a certain percentage of the total project budget. This percentage can be adjusted to incentivize production in areas that are in need of development and disincentivize non-productive projects. The local bureaucrats can also be monetarily rewarded for efficiently allocating their collected funds to foster urban development, creating a positive feedback loop. It also actively makes them more productive workers by fairly compensating them as they are severely underpaid in the local government offices. Hence, Speed Money can be changed from being an illegal tool for greasing the wheels to a productive tool for urban development.

The story of corruption is one that can be told from many different lenses, but is usually only told from one. I aim to highlight the ways in which developing countries like India have worked through corruption and can possibly benefit from legalizing it. When looking at only the drawbacks, one forgets that corruption is deeply embedded into all levels of government in India and that it cannot just be removed from the system. Dealing with corruption requires generations of legislation and reform. Ang’s work goes a long way towards helping policymakers tailor anti-corruption strategies to these very diverse contexts, moving away from a one-size-fits-all approach (Ang, 2020). By using her framework to measure, report, and legalize corruption, we can go a long way in converting these drawbacks to benefits.

References:

Ang, Y. Y. (2020). China’s gilded age: The paradox of economic boom and vast corruption. Cambridge University Press.

Ang, Y. Y. (2020). Unbundling corruption: Revisiting six questions on corruption. Global Perspectives, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2020.12036

Clark, D. (2021, June 24). An analysis into local government corruption in India. Medium. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://educationforindia.medium.com/an-analysis-into-local-government-corruption-in-india-b7bb74b0ed83

Dharia, N. V. (2021). Embodied urbanisms: Corruption and the Ecologies of eating and excreting in India’s real estate economies. Cultural Anthropology, 36(4), 708–732. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca36.4.11

Pani, N. (2018, January 8). Why urban planning is such a joke in India. Why urban planning is such a joke in India – The Hindu BusinessLine. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/columns/narendar-pani/why-urban-planning-is-such-a-joke/article9918465.ece

You can reach the author of this piece, Ritwick Dutta, at: rd3203@nyu.edu

You can reach the editor of this piece, Calley Wang, at: csw9856@nyu.edu