We know what’s wrong with HUD’s methodology for AMI, so what would it take to finally improve it?

There’s a strong case to be made that AMI – Area Median Income – has earned itself the title of “Most Important Three-letter Acronym” in the housing and urban planning world. “Affordable for who?” has been a tenant advocacy rallying cry for years, and now policy makers are more thoroughly interrogating what “affordable” really means – all through the framework of AMI. For those unfamiliar, the term “AMI” is generally used as a stand-in term for the annually-updated local income limits published by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)1 used to calculate the maximum allowable rent (30% of the income) for many of the most significant housing programs, including Section 8, low income housing tax credits projects, and more. AMI is as impactful a metric as it is vexing, and there aren’t many housing policy discussions that don’t rely on the term in some way. But for me and AMI, the beef is personal.

In my video application for graduate school, I spent my minute explaining what I judged to be a juicy and succinct policy question: why does the measure of AMI in New York City include parts of Westchester, Putnam, and Rockland countries? I even filmed the first half at an empty lot in Brooklyn, and the second in front of a mansion in Scarsdale. I thought it was all very clever.

Note the obligatory scare quotes around the word “affordable.”

Fast forward to my first day as a graduate researcher at the NYU Furman Center, I discovered my jab at AMI was little more than a “widespread misconception,” according to the Furman Center’s own research. The impact of the geographic barrier, Furman said in 2018, is dwarfed by the impact of what HUD calls the “High Housing Cost Adjustment” (HHCA)2. In markets with relatively high housing costs (think: any major city) the AMI actually tracks Fair Market Rents (FMRs) rather than Median Family Income estimates – meaning AMI is really, in most cases, a measure of rent levels that has been elaborately converted into units of annual income. That adjustment is far more powerful in inflating the AMI than the wide geography, as the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development thoroughly breaks down. As a result of this inflation, as ANHD’s Sarah Internicola argues, a significant share of the units framed as “affordable” in our housing policy are totally out of reach to extremely low-income renters (households of three, for example, earning less than about $36,000), though these households make up a majority of rent-burdened tenants.

The methodology is convoluted, and hard to understand. That’s part of the problem. HUD’s methodology takes census data, adjusts them for inflation, caps year-to year growth, and compares them to national incomes. In 2023 HUD added more steps and data to respond to pandemic challenges, making it even more confusing.

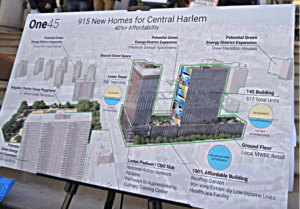

Even I, a longtime AMI nerd, found my head spinning trying to follow these changes. But people affected by AMI don’t really have a voice in how it’s shaped. Because FMRs and AMI are used so widely, the interest groups with a stake in the outcomes of HUD’s process range from families using housing vouchers and their advocates, to local governments who – in hot markets like NYC – budget to help cover the gap between federal funding and the steep local need, and the owners of LIHTC or Project-based Voucher properties. Instead, housing agencies for major cities (NYC, LA) or national real estate accounting firms (e.g., Novogradac) with serious technical capacity dominate the conversation. And recommendations are frequently less concerned with accuracy or precision and much more concerned with the ends: whether income limits and maximum rents are going up or down and by how much. On a data matter so technical, when only the most interested interest groups have the capacity to weigh in, the result is that AMI becomes increasingly detached from actual household incomes, and is instead calibrated to balance the competing needs of different parties. The weaker and more decontextualized AMI becomes, the weaker it is as a tool for organizers, advocates, and policy makers. AMI thresholds are the units of negotiation for affordable housing – just look at the controversy over AMI levels at the proposed ‘One45’ project in Harlem. Whether you’re a community organization pushing to include more deeply affordable units in a proposed development or a housing official trying to increase affordable housing options in high-income neighborhoods, you rely on the meaningfulness and accuracy of AMI to fight for and implement your goals.

So, how could we improve this cumbersome mechanism? One answer lies, to my surprise, in a never-acted-upon HUD report predating my video and the current controversy over AMI. They recommend simply decoupling the maximum rent calculation from the income eligibility limits for a given program. Under the present system, an increase in the income limit of $2,000 would necessarily mean that the monthly rent under those programs would also increase by $50. They recommend instead setting income limits using AMI but determining maximum rent levels using Small Area Fair Market Rents. As HUD argues, setting rents at 30 percent of the income limit guarantees that any household earning less than the limit is paying more than 30 percent of their income.

This would help to alleviate the issue of such strong, competing interests in the AMI by no longer pitting affordable housing advocates who want to see lower, more realistic income limits against property owners who are interested in increasing the maximum allowable rent. But it would not resolve the artificial inflation of income measurements; to do that, HUD should go one step further and eliminate the HHCA entirely. Accurately measuring area incomes does not preclude us from also assisting families higher along that income spectrum – using the median income (or some nice, round fraction of it) as the cutoff for financial assistance is an arbitrary measure to begin with.

Nor would it resolve concerns over measuring rents or incomes at small geographies. Two households with the same income in Bushwick and Ridgewood, for example, would be differently eligible. Small Area Fair Market Rents would reproduce the dynamic of creating more affordable housing in lower-income neighborhoods and more expensive housing in higher-income neighborhoods, potentially reinforcing segregation.

But if we continue to lean on a methodology that has consistently underserved the lowest-income households by distorting what is “affordable,” we are setting ourselves up for failure. As both the Furman Center and ANHD concluded – no matter where exactly the AMI lands, New York City can and should dedicate greater resources to providing more deeply affordable housing. I think that conducting our housing policy debates with a more material and accurate version of AMI might be one of many steps needed to make that happen.

1 “HUD” used to be a Top 5 TLA (three-letter acronym) but they’re honestly pretty quiet lately.

2 Awkward, sounds like it has do with health, 3/10 acronym

You can reach the author of this piece, Todd Baker, at: tb2753@nyu.edu

You can reach the editor of this piece, Patrick Spauster, at: ps4375@nyu.edu