With New York City’s transportation system headed to financial ruin, will disabled riders be left behind?

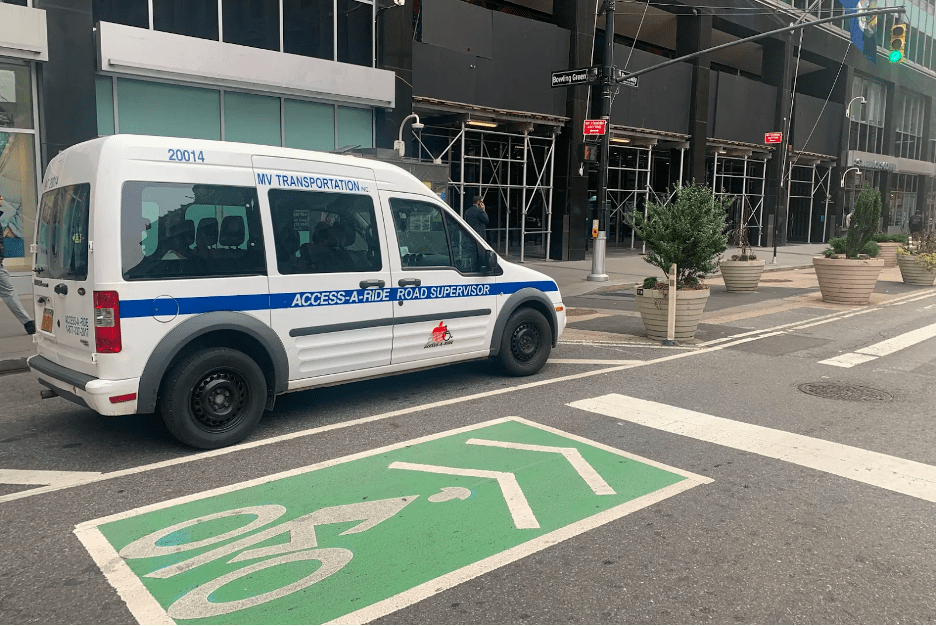

Photo Credit: Jose Martinez, THE CITY

The MTA’s paratransit system, Access-A-Ride, providing door-to-door shared bus service for disabled New Yorkers who are unable to use other MTA services, faces an uncertain future given the MTA’s ongoing fiscal crisis and reluctance by both New York State and City to provide additional funding. Without a strong commitment from either, the system could see a decline in service or service cuts, despite the success of its e-hail pilot and faster ridership recovery than general MTA subways and buses.

In her January ‘State of the State’ address, New York Governor Kathy Hochul praised the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) as the “lifeblood of the New York City metro region” and pledged to address the system’s substantial budget crisis. With long-term debt of $40.1 billion and a significant drop in revenue due to reduced ridership since the beginning of the pandemic, the MTA approved its $19.2 billion annual budget in December, which included a set of proposals to reduce the agency’s projected 2023 deficit of $2.6 billion. These include a 5.5% increase in fare and toll prices, subway service cuts on weekdays, and $600 million in unspecified additional government funding. With the remaining federal pandemic aid expected to dry up by 2025, the agency hopes that the state or city will step in to provide that earmarked funding.

The Governor’s budget, however, has limited details on how Albany specifically will help paratransit riders. In the full budget, released this month, Governor Hochul instead called for “nearly $500 million of increased annual contributions from New York City for MTA’s paratransit costs” along with funding for student MetroCards and PMT tax offsets. In the days since, New York City Mayor Eric Adams rebuffed this pledge, stating “while we recognize the significant fiscal challenges the MTA faces, we are concerned that this increased commitment could further strain our already-limited resources”. With neither fully committed to providing additional paratransit funding, it is unclear how the system’s budget problems will affect the perpetually-troubled Access-A-Ride system and its riders, who have limited alternatives.

These fears are warranted, given that New York’s paratransit services have faced cuts before. When public transit ridership hit an all time low in 2020 and federal funding was depleted, the MTA created a ‘doomsday plan’ in case Congress failed to provide additional aid. That proposal included a 40% reduction to city bus and rail service, a 50% cut to commuter rail, and an indefinite delay on capital projects, including elevator installation and other improvements to increase the number of accessible subway stations. It also proposed eliminating the e-hail pilot altogether. While this never came to fruition, accessibility programs could once again be on the chopping block if neither the state or city will commit to funding them.

The ridership numbers bear out just how essential the service is. AAR riders returned to the service after the onset of the pandemic faster and in larger volume than other public transit. While all city buses are handicap accessible, only 25% of subway stations are ADA-compliant, making the service essential to disabled New Yorkers’ ability to go about their everyday lives – going to work, seeing friends, attending doctor’s appointments, etc. General subway ridership continues to languish around 60% of pre-pandemic levels, while paratransit ridership has been near 80% since mid-2021. The number of paratransit rides per month continued to increase over 2022 with total monthly rides well above 500,000 since March last year and daily weekday rides around 28,000, similar to pre-pandemic levels. AAR ridership is expected to fully return to 2019 levels in 2023.

Despite high ridership, the system is rife with scheduling and reliability issues that make it cumbersome or impractical for daily use. Rides must be scheduled at least 24 hours in advance, either online or over the phone, and fares must be paid in exact cash. Once confirmed, riders are expected to wait up to 30 minutes after their scheduled pickup time because drivers are not considered ‘late’ until at least a half-hour has passed. Drivers, however, only have to wait five minutes for passengers and they are not required to contact the rider if they do not see them upon arrival at the pickup location. This leads to riders waiting hours for a scheduled ride, if it even arrives at all. An audit by the New York City Comptroller found that these policies left around 32,000 customers stranded in 2015 alone. Given that the rides are shared and destinations can be far apart from one another, customers are often traveling around the city for significantly longer than they would using general bus or subway service. One rider said it took 2.5 hours to travel from the Upper West Side to Penn Station on Access-A-Ride. This journey would take around 30 minutes on the subway or in a personal car.

Such issues led to the launch of an ‘e-hail’ pilot program in 2017. This allows riders to call accessible cabs on-demand through the Curb or Arro app at $2.75 per trip (the city covers the remaining cost). The pilot program has been called a ‘‘godsend’ by many users, as it is one of the few on-demand travel options available to disabled riders. However, the program is small – only 1,200 of the over 172,000 AAR-approved users were allowed to enroll in 2017 on a first-come, first-serve basis and it has not grown since. The MTA attempted to end the service in 2019 due to its high operating costs, but the pilot’s popularity forced them to ultimately abandon this plan and they promised in 2020 to double the number of e-hail users to 2,400. The long-awaited expansion, delayed by the pandemic, is expected to occur early this year, though advocates fear that the system’s financial crisis could lead to further delay.It also raises the possibility of user restrictions, like a previously proposed cap on the number of e-hail rides allowed per month.

There is one initiative in the Governor’s current budget that explicitly includes state funding for paratransit services, but it is unclear whether Access-A-Ride is able to benefit from it. The executive budget includes a $10 million ‘Innovative Mobility Initiative’ program to expand service offerings for non-MTA transit authorities, allocating $1 million each to seven of the largest non-MTA transit systems (they are not named) and establishing a five-year, competitive fund of $3 million for smaller systems. The details of this are fairly limited, but the bill notes that funds can be used to “purchase smaller vehicles for paratransit” and “establish and expand microtransit and paratransit products”. Over half of AAR rides are provided through brokers, but the wording of this initiative does not clarify if this funding will be open to brokers that are contracted to provide MTA services.

As the MTA heads towards a financial cliff, the fate of New York’s paratransit services is uncertain, despite its resiliency during the pandemic and the success of e-hail services. Given Access-A-Ride’s long history of unreliability and poor service, the Governor needs to ensure that disabled New Yorkers are given the same rights and access to the city as their non-disabled neighbors.

You can reach the author of this piece, Emily Speelman, at: eks2080@nyu.edu

You can reach the editor of this piece, Patrick Spauster, at: ps4375@nyu.edu

As dramatic as it may seem, without having the services of Access-A-Ride, I will find it difficult to leave my home. I fear the streets and with the services given, it allows me to function as a normal human being. I’ve used the service for 20 years, I’m older with more handicaps than before.

Even though Access-A-Ride may not be dependable, I am grateful that it has afforded me a way of functioning in society. E-Hail is a blessing knowing I can call with an emergency and get an auto

ASAP. I can get to my Doctors and physical therapist, shopping, and visit my family. It’s very serious if this program is limited or stopped.

Ehail is all I have to travel. As a disabled father with multiple disabilities, I depend on the ehail program as my digestive system often will not allow to wait for late drivers or give me the luxury of knowing a day in advance if my symptoms would allow me to safely travel at designated windows of times normal Accessaride often requires for use in order to get to and from my appointments. Eliminating ehail would eliminate what little bit of life I have left that allows to function as a meaningful part of my family and as a father and husband. Ehail already made substantial cuts a while back. I can’t afford anymore cuts. It truly would infringe on my rights as it allows me the ability to attempt a pursuit of happiness not only for myself but for my family too as missing medical treatments not mention other commitments greatly affects me and my family. The MTA is massive and can make other cuts if needed. Perhaps business majors could compete to find ways to avoid cuts to ehail and better tech could stop fare evasion. Anything—just please don’t cut Ehail anymore.