More NYC transit riders than ever have limited English proficiency. Improving language access would benefit equity and the economy.

As New York City continues to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, residents in working-class and immigrant neighborhoods have gotten back to riding public transportation. Or in many cases, they never had a choice to stop doing so, unlike residents of wealthier neighborhoods with more white-collar workers. Those dedicated riders don’t speak English as well as New Yorkers on the whole. Even though the MTA translates some notices, like service change and public service advisories, into other languages, announcements within trains and buses as well as most permanent signage remain English-only. The transit system does not currently provide much in the way of language access for Limited English Proficiency (LEP) riders, a group that has grown in relative size since the pandemic. Increasing language access could make a big difference.

Limited English Proficiency residents live in neighborhoods with higher rates of transit use.

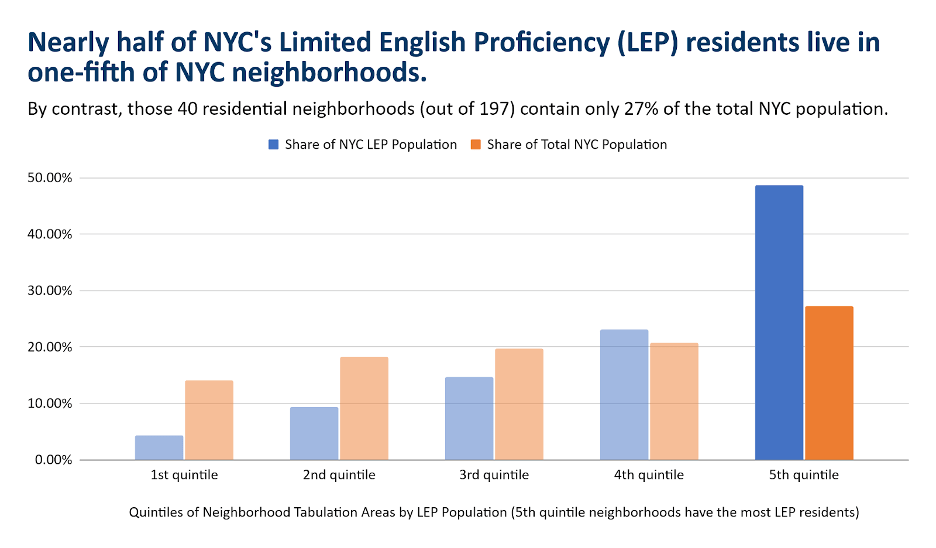

Almost half of NYC’s LEP residents live in just 40 of the city’s nearly 200 residential neighborhoods. While those 40 neighborhoods contain just 27% of the total NYC population, they have a disproportionate number of LEP residents. Elmhurst, Queens, for example, has over 45,700 LEP residents—nearly half of its population, and about 2.6% of the citywide LEP population. Meanwhile, its share of the total NYC population is just 1.2%.

Source: American Community Survey 2016-2020 by Neighborhood Tabulation Area (US Census, NYC DCP)

These neighborhoods depend on public transit to get to work. The average percentage of workers commuting with public transportation is 56% among neighborhoods with over 8,300 LEP residents (the top two quintiles by LEP population), compared to a citywide average of 51%. By contrast, on average less than 48% of workers commute on public transit among the 118 neighborhoods with fewer than 8,300 LEP residents (the bottom three quintiles).

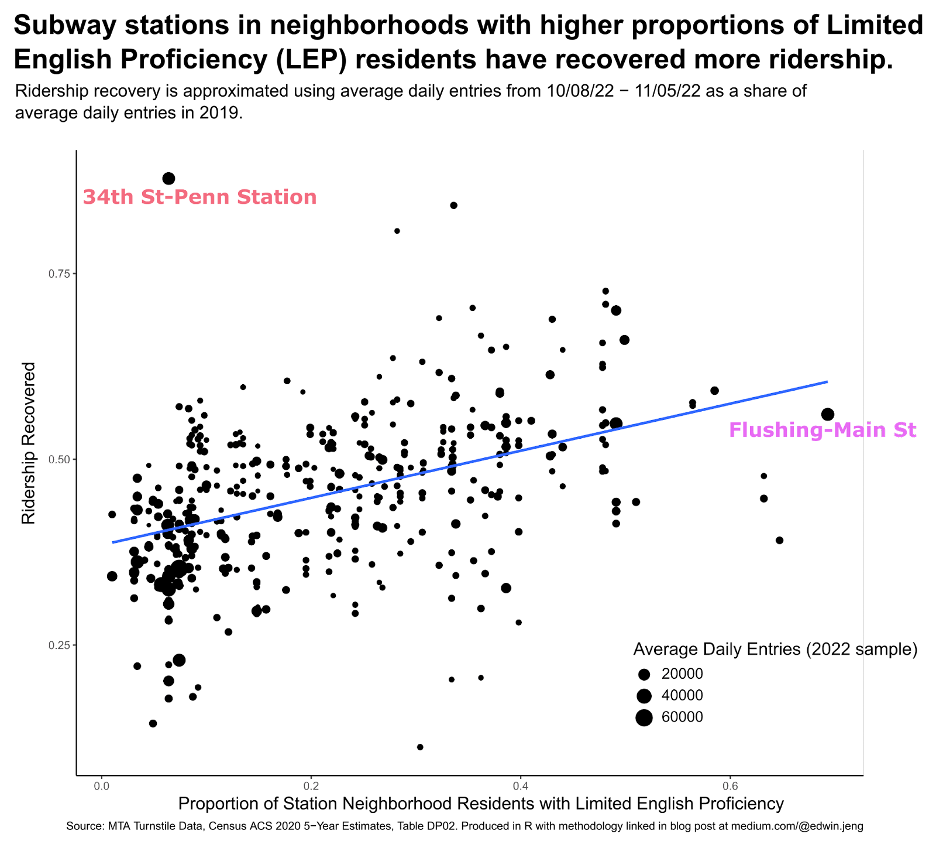

Subway stations in neighborhoods with more LEP residents have recovered more of their pre-COVID-19 ridership.

From October 8, 2022 to November 5, 2022, the average subway station citywide still only saw 45% of its daily entries compared to 2019. In contrast, the average station in a neighborhood with over 17,500 LEP residents (a category containing 20% of stations) had rebounded to 51% of 2019 ridership.

The disparity in recovery is even more apparent when comparing the stations with the highest and lowest proportions of LEP residents in their surrounding neighborhoods. The 38 stations in neighborhoods with over 40% of their residents having limited English proficiency have recovered 55% of 2019 ridership on average. As an example, Flushing-Main St, the station with the highest proportion of LEP residents in its surrounding neighborhood, has recovered roughly 56% of its 2019 ridership. By contrast, for the large group of stations in neighborhoods with LEP residents making up less than 10% of the population, only 40% of 2019 ridership has been recovered on average.

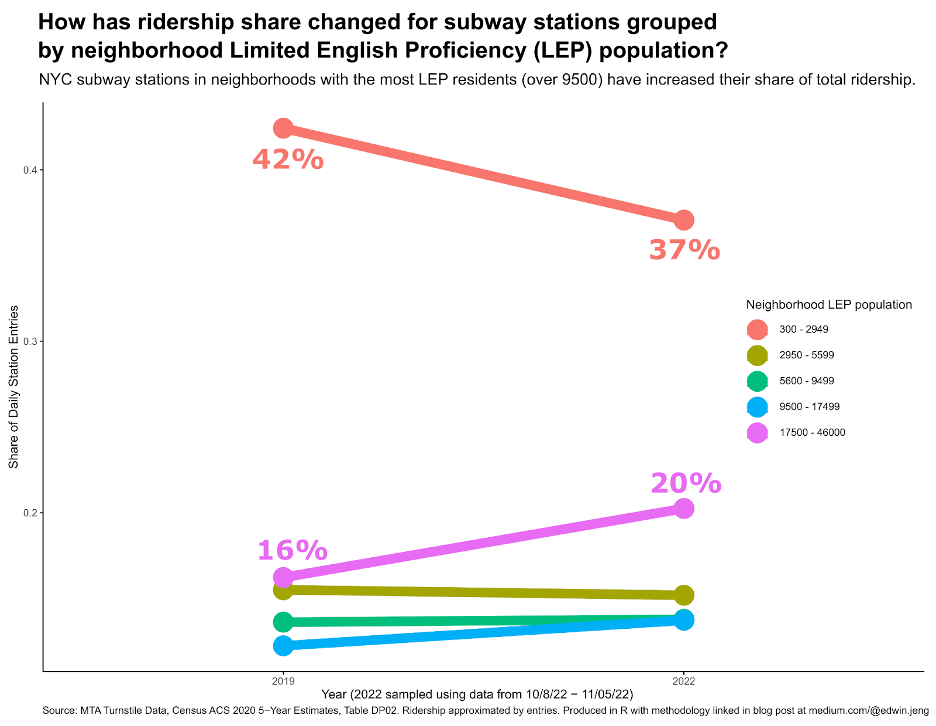

Furthermore, subway stations in high-LEP neighborhoods make up a measurably growing proportion of total ridership. The stations in neighborhoods with the most LEP residents (the top 40% of stations in terms of their neighborhoods’ LEP population) have seen their share of total ridership on an average day increase since the pandemic. On the flip side, stations in neighborhoods with the fewest LEP residents now represent a significantly smaller share of total ridership.

Language access improvements could benefit the economy and make the city more equitable.

For an LEP resident, poor language access could mean taking the wrong train, missing their stop, getting lost, or being late—stressful scenarios that mean wasted time at the very least. Citywide, this lack of language access could be causing losses in economic productivity from LEP residents, whether that stems from lateness or un(der)employment. As New York recovers from the economic impacts of COVID-19, the city and the MTA would also benefit from improving language access for non-residents, such as non-English-speaking tourists, who may be choosing other forms of transportation if they avoid transit in part due to language barriers.

Equally importantly, improving language access on transit helps achieve more equitable outcomes for LEP New Yorkers. Given that many LEP residents rely on public transit, difficulty navigating the transit system may be translating into fewer trips, greater isolation, and more limited experiences of the city. According to the NYC Health Department, language barriers can contribute to loneliness and other mental health issues. Even if LEP residents are memorizing their routes to and from work, trips to unfamiliar parts of the city are more difficult. Facing language barriers, LEP residents may be avoiding “unnecessary” travel or relying on others for transportation — reducing independence and access to recreational spaces, medical services, and other destinations. Improved language access could help make traveling to see family or friends or even just for leisure as much of a possibility for LEP New Yorkers as it is for native English speakers.

You can reach the author of this article, Edwin Jeng, at: ej737@nyu.edu

You can reach the editor of this piece, Patrick Spauster, at: ps4375@nyu.edu