Mayor Adam’s City of Yes means yes to green infrastructure, yes to more commercial space, and yes to zoning liberalization

Mayor Eric Adams has been pushing New York as a ‘City of Yes’ since June – his vision to turn New York City into a more inclusive and equitable place to live and work. But until this month, it’s been unclear what exactly that means.

This past month, the Department of City Planning held two public information sessions to elaborate on ‘City of Yes’ initiatives and hear from community members. The plan is driven by comprehensive zoning text amendments to break down barriers and allow smoother development processes.During last week’s information session, city planners delved into the goals of each zoning initiative and provided real-life examples to illustrate how ‘City of Yes’ will meet the city’s climate goals, support growing businesses, and increase the city’s affordable housing stock.

City of Carbon Neutrality

In New York City, over 70 percent of greenhouse gas emissions are driven by the building sector. The City of Carbon Neutrality would build upon existing initiatives like the city’s first green zoning overhaul, which loosened restrictions on energy-efficient retrofittings, and the 80×50 roadmap, the city’s concrete plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 80% by 2050. Nilus Klingel, senior planner at the DCP, argued that zoning tweaks can eliminate obstacles that hinder climate-smart investments.

The city’s current zoning codes make it nearly impossible to achieve a carbon-neutral city. For instance, existing zoning limitations leave little opportunities for solar rooftops and building retrofits due to height limits and maximum permitted floor area ratio (FAR) rules. Additionally, existing zoning is lagging in critical climate areas, such as energy storage, electric vehicle charging locations, and stormwater management.

In one example Klingel provided, changes like updating zoning regulations for street trees can be implemented to provide opportunities for more environmentally sustainable designs, including new streetscape prototypes for curbside rain gardens, which disproportionately don’t have trees.

This plan hopes to fix long overdue impediments such as transitioning the grid from fossil fuels to renewable energy, accommodating a larger range of building retrofits, updating solid waste and water zoning regulations, and supporting the growth of electric transportation and micro mobility.

City of Economic Opportunity

Many business owners across the city struggle due to confusing and inconsistent zoning restrictions and design rules in existing commercial districts. Other restrictions, like existing remnants from the 1926 Cabaret Law, hinder neighborhood and economic vibrancy for emerging nightlife. Matt Waskiewicz, from the Economic Development and Regional Planning Division at the DCP, discussed the City of Economic Opportunity’s plan to allow the repurposing of existing and creation of new spaces to accommodate the city’s growing businesses.

Zoning for the City of Economic Opportunity would liberalize commercial districts by allowing same use types in similar districts and permit more activities that are currently restrained.

In the examples Waskiewicz provided, businesses currently don’t have the flexibility to grow due to zoning restrictions on certain activities, density restrictions for businesses that want to relocate, and square footage restrictions on businesses that want to expand.

The plan would allow for the same mix of businesses in C1 and C2 districts, such as allowing both bicycle sales and rentals or repairs shops to operate within the same neighborhood commercial district. The plan would also allow similar mix of businesses activities in higher density areas, like C4, C5, and C6 districts. This would provide currently restricted businesses in higher density districts, such as art and dance studios, to easily relocate and operate across neighborhoods.

Furthermore, current zoning regulations for economic development are outdated, as they don’t provide tools for growing industrial buildings. For instance, the owner of a film lighting business located in a 1-story industrial building in Queens (pictured below) cannot expand to add more floors above the storage area on the ground floor under the current zoning code. This puts them, and other owners of industrial buildings, at risk of relocating outside of the city in order to grow their businesses.

One story industrial building in Sunnyside, Queens (Department of City Planning)

The plan would accommodate for the city’s growing business sector by updating commercial districts to mirror the evolving needs of businesses and create new mid-density districts for the expanding industrial business sector.

City of Housing Opportunity

Lastly, Veronica Brown and Winnie Shen from the Housing Division at the DCP discussed how zoning for housing opportunity will achieve some of the long-awaited goals for one of the city’s most prevalent issues: affordable housing. The planners emphasized the need for all neighborhoods across the city to participate in order to remove obstacles to equitable housing development.

Changes to the zoning regulations would take advantage of existing, yet underutilized, space in the city by simplifying complex zoning restrictions to unlock more housing opportunities in low-, medium-, and high-density districts across all five boroughs. Zoning reform will also accommodate for the diverse needs of owners by allowing more housing types that will serve a wider range of people, such as ADUs, smaller units, and shared housing.

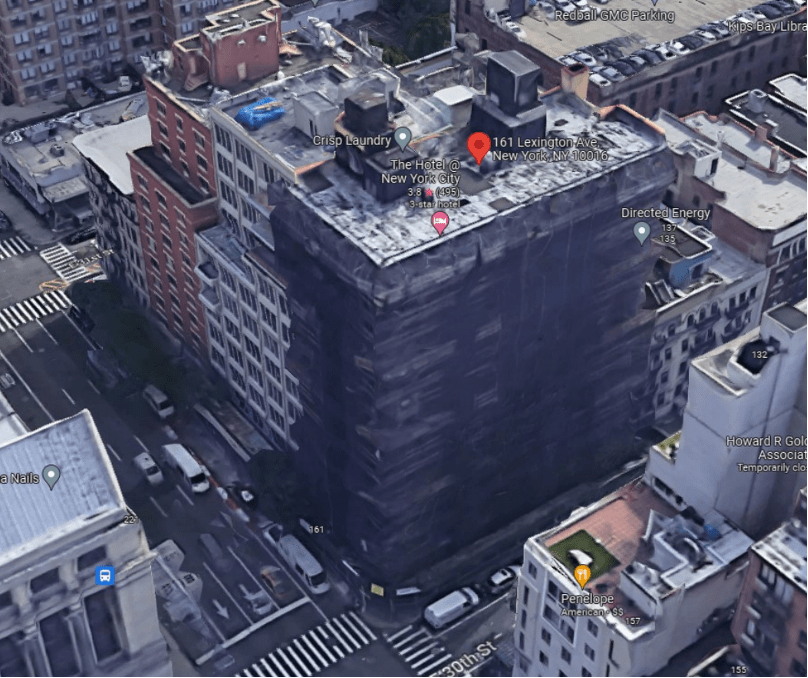

Existing zoning is extremely limited in accommodating for conversions of underutilized and vacant spaces. In one example, the planners explain how certain rules don’t accommodate for supportive housing if the existing site is an overbuilt high-density building. For instance, a housing non-profit organization that acquires a vacant hotel in Manhattan is subject to conversion obstacles since the current zoning code would classify it as a community facility instead of residential. Zoning reform would change the rules to allow conversions to be more broadly applicable for more supportive housing.

Vacant hotel in Kips Bay, Manhattan (Department of City Planning)

The plan would also adjust the current waiver threshold for parking requirements, a long-contested rule that many owners try to bypass by developing under the threshold amount of housing units. By restricting parking requirements, owners will be allowed to build more housing on a site instead of setting aside space for parking, providing more opportunity for a larger housing stock across the city.

Zoning as the Solution

Reforming New York City’s Zoning Resolution is not a new or far-fetched idea. Criticism regarding zoning reform has been in conversations for many years, especially the discriminatory effects of restrictive and exclusionary zoning. New York state, in particular, has been cited as having some of the worst exclusionary zoning in the nation. While the state has been rolling out a number of zoning reform legislation this past year, Mayor Adams is in a unique position to pivot New York City from the inequitable zoning decisions of his predecessors and remove red tape to use zoning as a tool for unlocking more climate resilience, economic growth, and housing opportunities. Though Adams can only do so much through administrative rule changes – broader scale zoning reform would require City Council approval.

To keep up with progress on City of Yes, read more here.