NYC’s new green infrastructure is missing a huge opportunity to advance environmental justice

When it rains, sewage overwhelms New York’s antiquated sewer system and pours into the rivers that surround the city. It doesn’t take much. Two inches of rain is enough for the sewer system to get overwhelmed. In 2020, New York’s overflow sewage volume totaled more water than the residents of San Francisco use in their homes in a year by several billion gallons. That excess stormwater runoff is a major source of pollution because it increases the risk of flooding and limits where New Yorkers can safely swim, fish, or row. As sea levels rise and New York receives more intense downpours and coastal flooding, this problem only becomes thornier. Without addressing sewer overflow, frontline communities will be flooded with a mixture of stormwaters and raw sewage.

New York’s Department of Environmental protection is focused on reducing stormwater runoff, but so far it has focused on smaller scale street projects and ignored the secondary benefits that trees can provide to neighborhoods, missing a huge opportunity to advance environmental justice.

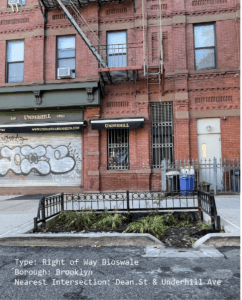

Stormwater runoff solutions tend to fall into two categories: gray infrastructure and green infrastructure. Gray infrastructure encompasses the traditional sewer treatment tools, such as constructing new sewage treatment plants and new tunnels to hold more stormwater. A majority of the city relies on gray infrastructure – an 1800s combined sewer system design. This system mixes sewage with snowmelt and rainwater and sends all of it to a sewage treatment plant before returning clean water to the city’s waterways. Alternatively, green infrastructure involves creating more parts of the city where stormwater can be captured before it reaches the combined sewer system by engineering new permeable surfaces, green roofs, rain gardens, and bioswales.

In its most recent plan New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) opted for a mixture of green and gray, allocated $2.7 billion to gray infrastructure and $1.6 billion to green infrastructure to spend between 2011 and 2030. Through design contracts and grants to private landowners, DEP has helped complete 10,800 green infrastructure projects across the city. There are another 3,400 projects in either the design or construction phase now, and perhaps more that have yet to be announced.

DEP’s green infrastructure is small and mostly built in the street.

DEP remains focused on meeting its stormwater capture goals. However, projects that are getting built tend to be smaller in size. So far, 93 percent of them have been built on city streets and sidewalks, the area known as right-of-way, instead of onsite at a building or lot of land. Because street bioswales need to be squeezed into streets and sidewalks that already serve many purposes, the projects end up being quite small. Of all documented DEP projects, onsite projects are more than 50 times larger than projects built in the right-of-way. Building mostly in the right-of-way may be leading to DEP building fewer square feet of green infrastructure overall.

It’s not all bad. The right-of-way makes up 30% of all impermeable paving in New York, meaning that placing green infrastructure here can have a huge difference on how much stormwater can seep naturally into the soil and not flow into the sewer system. Projects in the right-of-way are also more visible to the general public (more people pass by a sidewalk rain garden than notice green changes to an apartment roof).

Yet these trends may be limiting the impact of DEP’s efforts. From its most recent quarterly progress report, it seems like DEP “initially focused” primarily on building in the right-of-way and expects to use a broader array of strategies in the future. However, 11 years into building green infrastructure, DEP still seems to be sticking to right-of-way projects, with 92 percent of projects in the pipeline sited on city streets and sidewalks.

The green infrastructure getting built isn’t greening neighborhoods

In New York green spaces and trees are inequitably distributed – poorer neighborhoods of color have less access to both. Planting more trees and making more green space to combat stormwater can help correct this dangerous inequity, lessening the harm of the urban heat island effect and improving air quality for residents.

But so far, only one third of right-of-way green infrastructure projects that DEP has built include a tree. This is true despite most projects having enough room for trees and research showing that including trees in green infrastructure improves stormwater absorption. Even more worrying is that DEP’s future right-of-way projects have even fewer trees. Compared to 35 percent of constructed projects that include trees, only 30 percent of projects under construction and a mere 13 percent of projects in the design phase include trees.

This raises environmental justice concerns: in Brooklyn, the neighborhoods where most of the design-phase projects are located are Crown Heights and Canarsie, two predominantly Black neighborhoods that score highly on the city’s heat vulnerability index. In that borough, only 9 percent of planned right-of-way projects include street trees.

There could be good reasons for the low rate of street trees among these green infrastructure projects. The Parks Department regulates tree spacing along with 19 other criteria, and green infrastructure has its own engineering rules that may make it difficult to plant a tree, including the grade of the street and the expected amount of stormwater that will drain into the soil. So far, DEP has not publicly discussed the value of trees in its green infrastructure.

DEP should prioritize building green infrastructure that provides other environmental benefits to the city beyond capturing stormwater.

There is still time for things to change. DEP still has many years and a good deal of funding that they can spend on green infrastructure, and the tree-less projects in the design phase can still be redesigned. It’s important that no more time is lost on this golden opportunity: DEP should prioritize building green infrastructure that not only captures stormwater but also provides other environmental benefits to the city.

There are many resources available to help in this task, especially from other city agencies. The simplest way to operationalize this goal may be through tree planting. Given trees’ benefits, it seems like an important but simple switch for DEP to begin asking why a green infrastructure project shouldn’t have a tree instead of why it should. The fact that other agencies are trying to tackle this task alongside DEP could open up opportunities for braiding funding, streamlining implementation, and fostering more creative design practices.

Green infrastructure is already a huge step in the right direction compared to gray infrastructure. However, the agency must continue to seek out creative solutions to reap the full benefits of this funding and infrastructure.